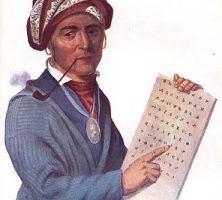

Sequoyah, or Sequoia (both spellings were given by missionaries, but in Cherokee the name is closer to Sikwayi or Sogwali), also called George Gist or George Guess, was the legendary creator of the Cherokee syllabary.

Born in a village in the mountains of Tennessee, he resettled in Arkansas when tribal land along the Little Tennessee River was ceded to whites in the 1790s. In 1829 he moved to Indian Territory, in present-day Oklahoma. He died in Texas or Mexico while attempting to contact fellow Cherokees who had moved even farther away from encroaching whites. Sequoyah visited northwest Georgia only sporadically, when he passed through or returned to advise eastern Cherokees on conditions in the West. He also traveled to teach the syllabary and to encourage its use among the far-flung members of his tribe.

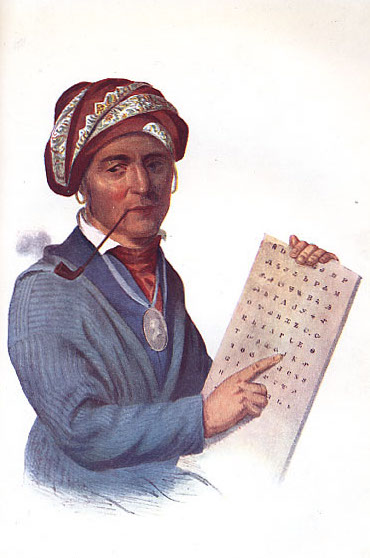

From the 1820s, when the syllabary became well known, until the 1960s, published accounts agreed that Sequoyah was the son of a Cherokee mother and a white father, almost certainly Nathaniel Gist, a commissioned officer in the Continental army and emissary of George Washington. Sequoyah nevertheless appeared to be a full-blooded Indian who remained true to the traditions of his people, never adopting white dress, religion, or other customs. In particular, he spoke no language other than Cherokee.

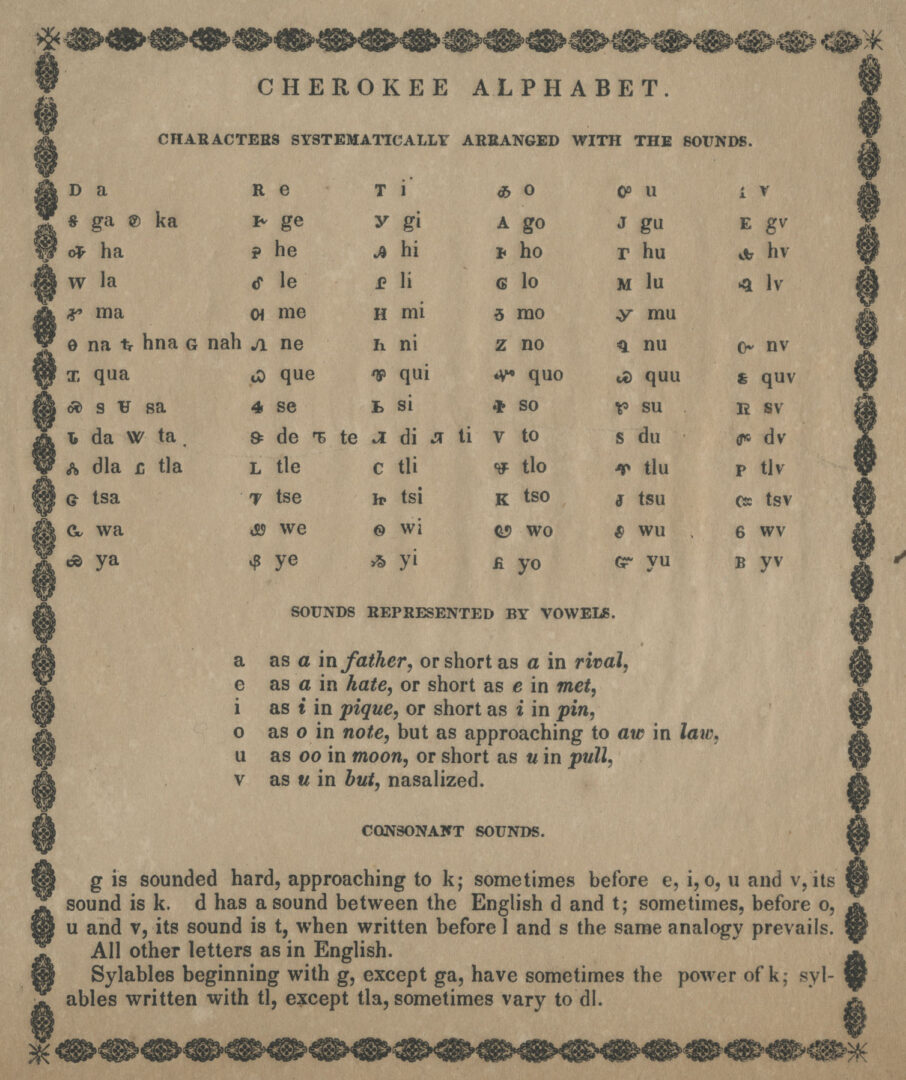

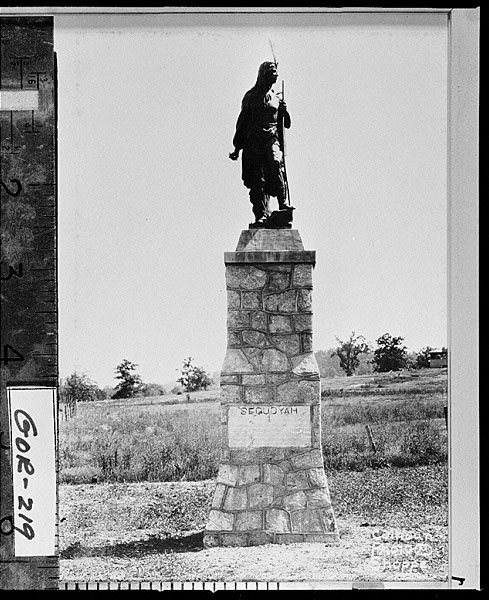

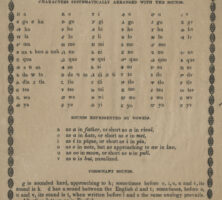

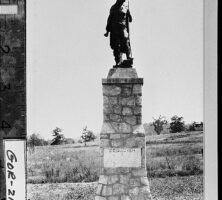

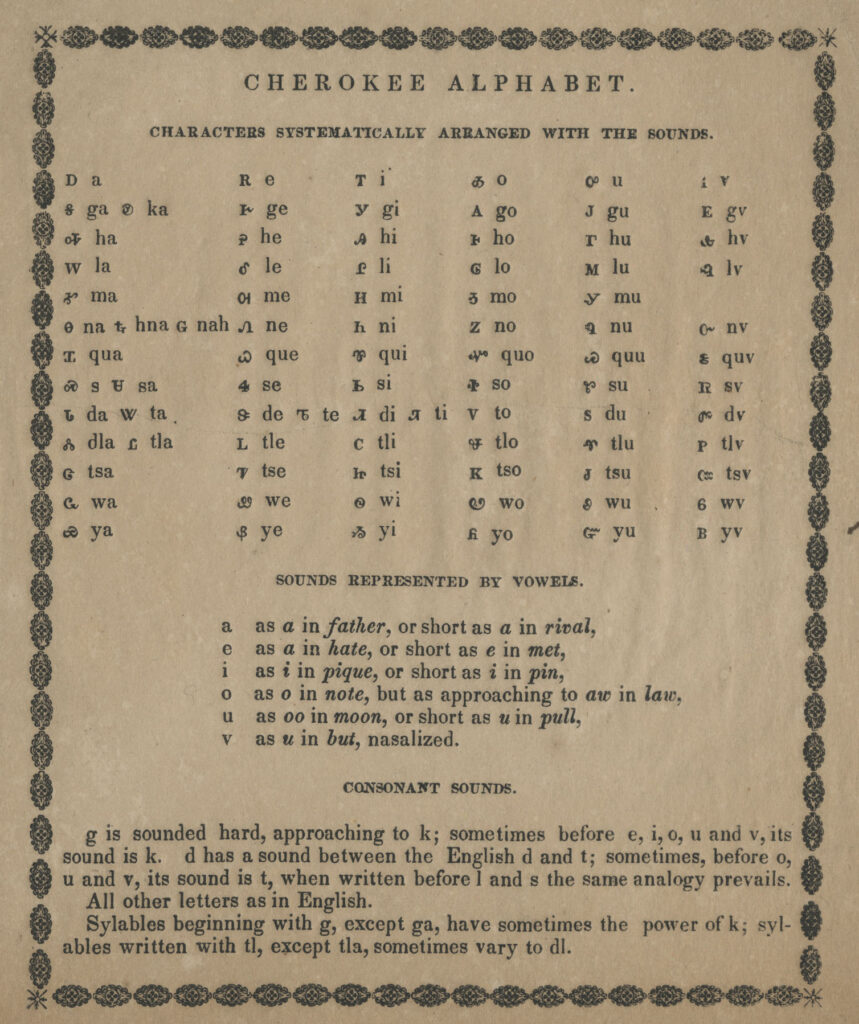

Impressed by the whites’ ability to communicate over distances by writing, Sequoyah invented a system of eighty-four to eighty-six characters that represented syllables in spoken Cherokee (hence it is a syllabary, not an alphabet). Completed in 1821, the syllabary was rapidly adopted by a large number of Cherokees, making Sequoyah the only member of an illiterate group in human history to have single-handedly devised a successful system of writing. This view is supported by firsthand accounts of missionaries to the Cherokees, government agents, and journalists who interviewed Sequoyah (or a man claiming to be Sequoyah) and statements of some people claiming to be Sequoyah’s descendants. It has been the basis of awards by the Cherokee Nation, the U.S. Congress, and various states. There are monuments, parks, and schools named for Sequoyah in Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Oklahoma, and other states. The giant sequoia tree, found in California, is named for him.

In 1971 Traveller Bird, claiming to be a direct descendant of Sequoyah, published the book Tell Them They Lie: The Sequoyah Myth, which posits a vastly different tradition. According to Bird, Sequoyah was indeed the full-blooded Native American he appeared to be, who all his life opposed the submission and assimilation of his people into white culture. He was also a scribe, trained in a Cherokee system of writing that predated contact with whites, and during his lifetime learned to speak English, Spanish, and other languages. Sequoyah’s politics and the syllabary were threats to those who portrayed Native American culture as primitive, including missionaries who sought to Christianize Indians, teach them English, and settle them in towns and farms modeled on white civilization, as well as politicians and military leaders who wanted to expropriate their lands. Assimilationist Cherokees accused Sequoyah of witchcraft, branded and mutilated him, and forged his name on treaties surrendering tribal land, while missionaries, unable to suppress the syllabary, fabricated the story of its miraculous creation. Images of Sequoyah are actually of another Cherokee who was illiterate, Bird says, and interviews with him never included demonstrations of writing. Bird’s book has stirred controversy because it challenges previously accepted scholarship without supplying written evidence, but it has also gained a place and some credence in academic discourse.

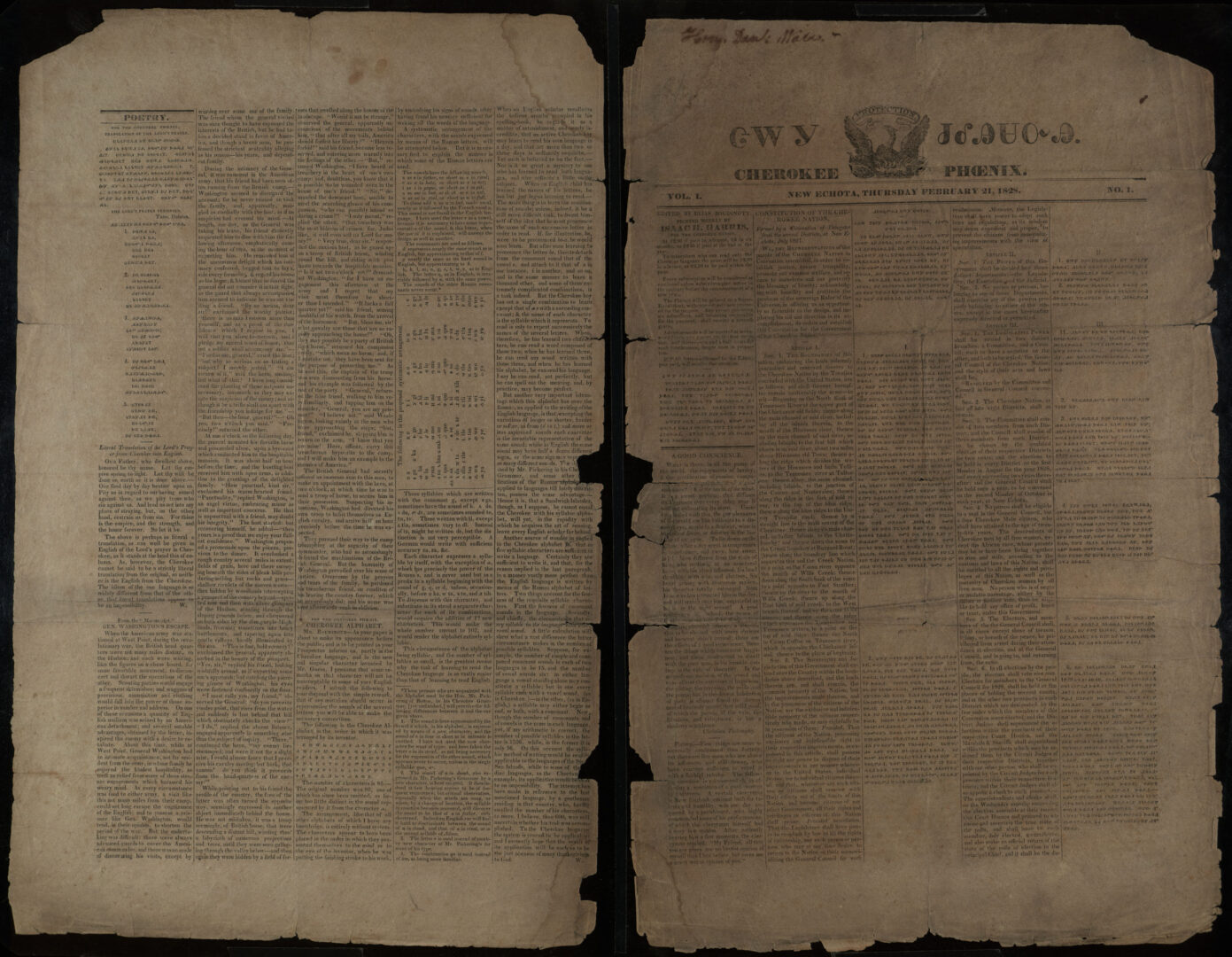

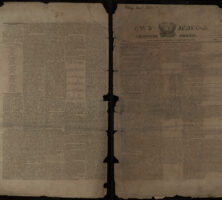

It is fact that the syllabary was used to print some articles in the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, published in New Echota, Georgia (then the capital of the eastern Cherokees), from 1828 to 1834. The appearance of the newspaper, as well as the organized government of the Cherokee Nation, including tribal council and supreme court, infuriated the state of Georgia, which had an agreement with the U.S. government (the Compact of 1802) to remove the Native Americans. When the Cherokees were removed, the buildings and printing press were destroyed, and the type for the syllabary was dumped in a well that was then sealed. Excavations in the 1950s led to partial restoration, and the New Echota State Historic Site opened near Calhoun in 1962.