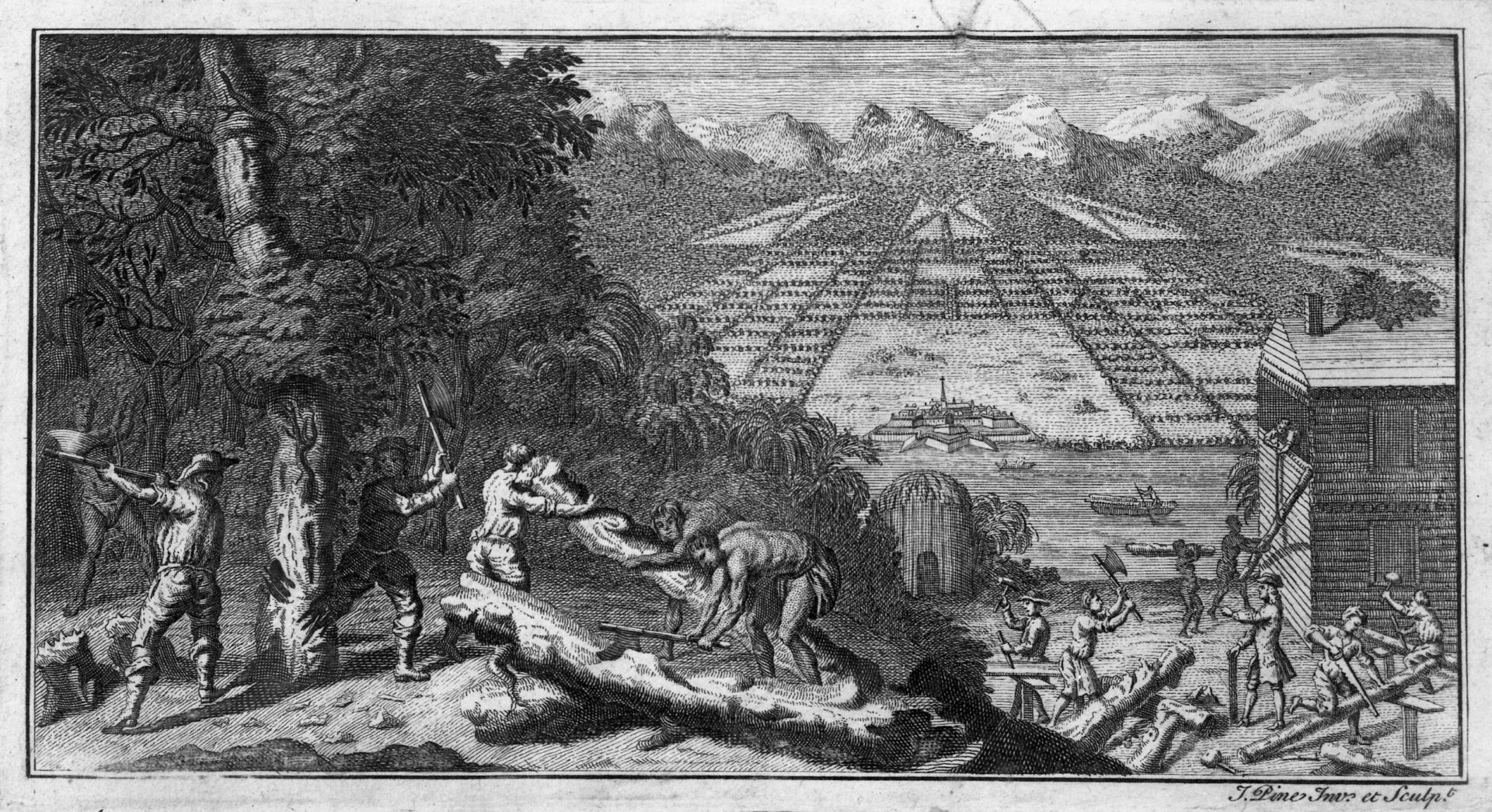

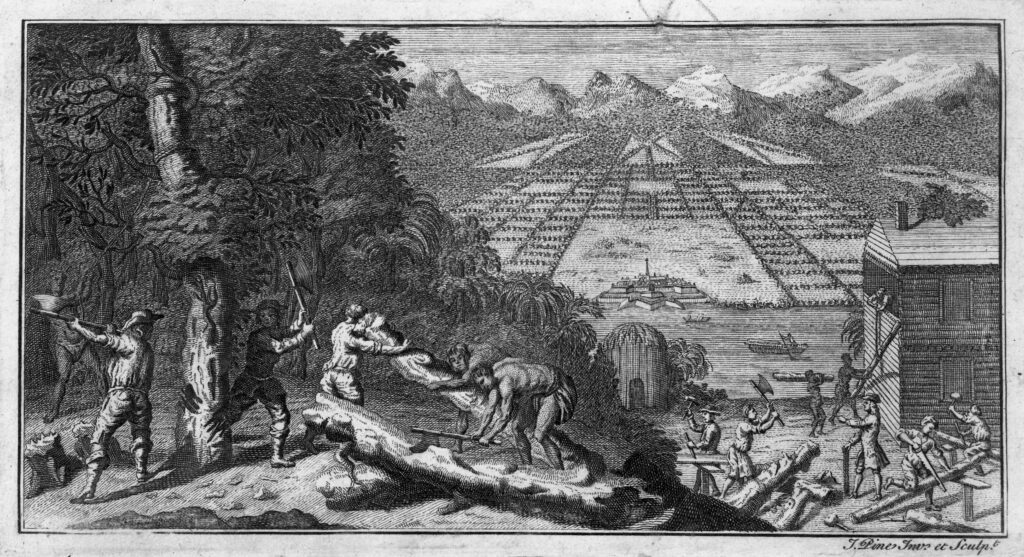

General James Oglethorpe established the Trustee Garden in Savannah in 1734, two years after the founding of the Georgia Trust, the corporate body that governed the colony from 1732 until 1752. The garden comprised about ten acres to the east of the area then settled. Dedicated to botany and agriculture, it reflected the scientific and commercial aspirations of the Trustees and their backers in England; its growth and demise over the next twenty years reflected the realities of climate, geography, and the lack of people on the ground and consistent support from London to further these aspirations.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The garden was to be modeled after the physick and botanical gardens at Oxford and Chelsea in England. The Society of Apothecaries had set up a model garden for medical plants in the seventeenth century. The garden in Savannah was also intended as an agricultural experiment station for the semitropical products, mainly silk and wine, that Georgia was to provide for its English sponsors and for the crown. The leaves of imported white mulberry trees were to feed the worms required in silk culture, and imported vines were to bear noble grapes. Other semitropical and Mediterranean products were to be grown as well, ranging from orange trees and capers to cotton and olives. The objective of this experiment was not so much to develop an indigenous economy as to use local labor—settlers and indentured servants—to provide staples and raw materials for goods to be further processed and consumed in England. They were there to supplant expensive imports from Spain and other Mediterranean areas, according to the mercantilist policies of the colonial powers of the eighteenth century.

Agriculture

Silk production was a major interest in London—and in all of eighteenth-century Europe—since silk products and raw silk were popular among the increasingly well-off English population. The garden, as an experiment station, was to provide large amounts of fresh mulberry leaves throughout the spring to people hired as silk makers. More important, the Trustee gardener was to supply sufficient mulberry seedlings for distribution to the settlers, who were required to plant mulberry trees on their plots as part of their land grants. But silk culture was labor intensive and demanded considerable experience and skills in raising the worms, which needed to be fed continuously during the spring before they wound themselves into cocoons. The Trustees therefore imported Italian silk makers to teach the colonists their trade.

Photograph by Wikimedia

Viniculture was promoted in particular by Philip Miller, chief gardener of the physick garden in Chelsea, but the noble grape vines would not flourish, despite the abundance of local grapes. Similar difficulties were encountered in the growth of imported fruit trees, chestnuts, and olives. One of the early gardeners, Joseph Fitzwalter, favored useful crops such as hops for beer and flax and hemp for naval riggings, but little came of these experiments.

One of the major reasons for the lack of agricultural success was the climate. Contrary to the assumptions of the Trustees and their advisors, Georgia was not subtropical but subject to considerable temperature fluctuations, particularly during the early spring. In addition, there was a lack of skilled labor. Silk making in Savannah was beset by constant strife between the Italian experts and local authorities; only in the German settlement of Ebenezer, with its centralized governance and economy, were silkworms raised consistently on settlers’ plots. But although the wife of the minister there set up a reputable sericulture that provided spun silk for fishing lines until the nineteenth century, neither wine nor useful and consistent yields of flax and hemp were obtained in the colony.

Medical Botanicals and Dyestuffs

The story of the Trustee Garden for medical botanicals—a physick or medicinal garden—had a similiar trajectory of high hopes and eventual decline, but has wider implicatons for the history of American plants and drugs. Following models in England, European herbs and medicinal plants were to be grown, as well as such native North American plants as snakeroot, ginseng, sassafras, and sumac, known since the sixteenth century for their medicinal properties.

Image from formulanone

The main objective of the garden was to serve as the experimental site for a reliable source of exotic botanicals from the Spanish Americas, in particular Jesuit or Peruvian bark (later known as the antimalarial quinine), which was in widespread demand for its fever-quenching properties. Demand was also high for ipecacuhana, an emetic, and cochineal, a plant parasite yielding the scarlet dye used for military uniforms and court dress. The Spanish had severely restricted the export of drugs and dyes that could challenge their monopoly, and Georgia seemed an excellent place to circumvent these restrictions.

Therefore, the physick garden was specifically sponsored by three major players in the drug trade of the first half of the eighteenth century. The first, the Society of Apothecaries, was a powerful company and guild entitled by royal charter to supply London and environs with drugs. It also held a monopoly to supply drugs, first to the navy and then to the East India Company, through a special stock of drugs prepared on the premises of the society.

The second major player was Hans Sloane, a renowned physician and naturalist, holder of a medical degree from the University of Orange, former physician to the duke of Albemarle in Jamaica, royal physician, president of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians. Sloane was a prolific collector of plant specimens and books on natural history, and a major patron of the physick garden at Chelsea.

From Kohler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, by F. E. Kohler

The third, Charles DuBois, was a treasurer of the East India Company, which was well represented on the Trustee Council. (It was no coincidence that tropical spices, on whose import into England the East India Company held a monopoly, were not included in the plans for the garden.)

Special funds were set aside for botanist William Houstoun in 1732 and after his death in Jamaica, for Robert Millar in 1734. The money was to finance travel across the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea down to the northern coast of Brazil and the collection of specimen for trans-shipment to Georgia. Although unsuccessful in wresting Jesuit bark and cochineal specimens from the Spanish, Miller sent contrayerva and Peruvian and Capivi balsam to his brother in London. Subsequent exports from Georgia to London did include local and Indian plant drugs, such as jalap, sassafras, snakeroot, and sumac. The German element at Ebenezer, however, did not contribute to the search for local drugs because they were supplied with proprietary medications from Germany.

Despite its brief and spotty success and its decline by the 1740s, the Trustee Garden in Savannah was characteristic of eighteenth-century scientific and utilitarian interest in the natural world. As an early transatlantic enterprise, its founders prefigured the independent American botanists of the end of the century.