William Bacon Stevens’s A History of Georgia, published in 1847 (volume 1) and 1859 (volume 2), stands today as a monument to the man and the society of which he was a founder. “It was a scholarly work, far beyond any other history which had ever appeared in Georgia or in a majority of other states, and has not yet been superseded,” wrote the eminent Georgia historian E. Merton Coulter in 1972. Yet at the time of its publication, Stevens’s long-awaited book stirred a controversy among historians across Georgia—partly, no doubt, because a northerner had dared to write the first scholarly history of the Deep South state.

Like his fellow Georgia Historical Society founder Israel K. Tefft, Stevens was a native New Englander, born in Maine in 1815. Traveling south for health reasons and to earn a medical degree at the Medical College of South Carolina, Stevens landed in Savannah in 1837 and quickly moved into the social circles of his new home. He joined the Georgia Hussars and other local clubs, married into a prominent Savannah family, and was such a part of the Savannah scene that, as one writer observed, he “might well have forgot his former self and assumed that his ancestors had adventured to Georgia with Oglethorpe.”

Stevens soon became friends with Tefft, from whom he learned much about the history of his adopted state. Lamenting the fact that Georgians had made so much history but had done so little to record it, the two hatched the idea of forming a historical society. “Our fathers have gone,” Stevens explained in the Savannah newspaper, “but their mantles have not ascended with them, and nobly shall we prove ourselves to be worthy inheritors of their fame, by garnering their deeds of valor, and by recovering and making permanent the annals of the early days of Georgia.”

Upon the formation of the Georgia Historical Society (GHS) in May 1839, Stevens was elected corresponding secretary and librarian. Two years later, he got a chance to fulfill a dream. At the society’s second annual meeting, on Georgia Day, February 12, 1841, Stevens delivered an address that so impressed the audience that the society proposed that Stevens write “a new and complete” state history. Readily accepting the challenge, Stevens began studying his subject, delivering the inaugural program in the society’s first lecture series in 1842 and then traveling the state to speak in Milledgeville and Augusta on behalf of GHS.

When the first of two volumes finally appeared in 1847, the reaction was surprisingly mixed. Although such publications as the North American Review and the Southern Quarterly Review were generally laudatory, Stevens’s fellow Georgians were not so kind. His book was attacked in the Augusta newspapers and in an anonymous pamphlet (the author was later discovered to be George Wymberley Jones) as repetitious and riddled with factual errors. The society was also criticized for having spent funds for publishing a history rather than collecting primary sources for publication.

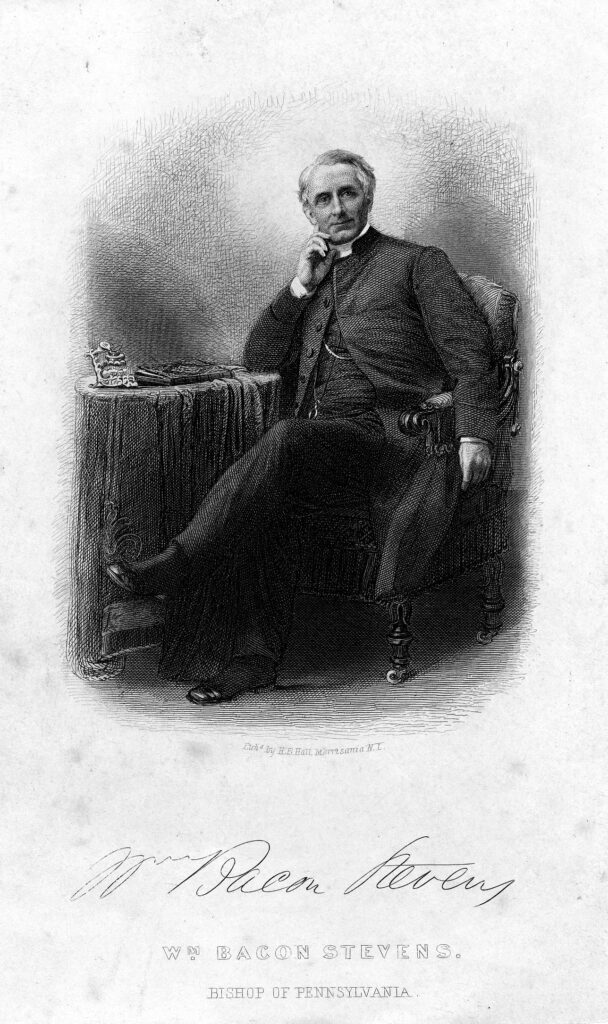

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The Georgia Historical Society rushed to Stevens’s defense. In the local papers GHS members claimed that the critics were motivated moreby a personal dislike of the historian than by “a fair and allowable criticism.” The historian William Harris Bragg agrees with this assessment, charging that more than one old-line Georgian envied the New Englander’s success and fame.

In the midst of pursuing his historical interests, Stevens abandoned his medical practice after five years and directed his attention toward the ministry of the Protestant Episcopal church. He was ordained as an Episcopal priest in February 1843. Appointed a missionary to Athens, he helped to establish a church there and in late 1844 accepted a position as professor of oratory and belles lettres at the University of Georgia. Four years later his religious duties took him to St. Andrews Church in Philadelphia, where he served until his death in 1887. His return to the North further angered a number of Georgians, who were indignant that someone they had accepted socially and had helped to prominence would, in their opinion, turn his back on them.

Whatever the source of this contemporary criticism, today Stevens’s work is considered the first scholarly attempt to tell the story of Georgia’s past. For this and his other contributions, he is honored by the society he founded with the William Bacon Stevens Award, presented annually for the best student article published in the Georgia Historical Quarterly, the scholarly journal of the Georgia Historical Society. Stevens would no doubt be pleased that his memory is associated with something he strove to promote: outstanding scholarship in Georgia history.