Georgia’s deep roots in Methodism reach back to the founders of the Methodist movement. Methodism is a major Protestant community in the state, and it includes four historically related denominations (listed in order of size): the United Methodist Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME Church), the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church (CME Church), and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion (AME Zion). These four denominations form the Pan-Methodist Commission on Union, created in 1996, and all share the theological beliefs and organizational structure common to Methodists worldwide.

Beliefs and Organization

The scriptures form the primary basis of Methodist theology and doctrine, which are also strongly influenced by the Nicene Creed of the fourth-century Christian church and the Anglican Church’s Book of Common Prayer. Methodists accept the idea of the Trinity, comprising God the Father, Christ the Son, and the Holy Spirit. According to John Wesley, who founded the denomination in 1729, the three primary doctrines of the Methodist faith are repentance, faith, and holiness. Rejecting the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, or the idea that God chooses an “elect” few for salvation, Methodists believe that redemption is available to anyone through a combination of faith and the “grace” of the Holy Spirit. Active efforts on the part of the believer, such as prayer and good works, are also encouraged by Methodist doctrine and practice.

Methodists are connectional, meaning that individual Methodist churches maintain ties with one another through annual conferences, which are organized by geographic proximity. The conferences also assign ministers to individual churches. Evangelism, or the act of sharing beliefs with those outside the church, is another important tenet of Methodism and began with John Wesley in 1739, when he embarked on a career as a traveling minister in England. Methodist ministers in America also traveled throughout the colonies to spread the denomination during the eighteenth century. This practice continued in Georgia well into the nineteenth century, particularly in rural, remote locations. Because ministers often reached these areas on horseback, they came to be known as “circuit riders.” Writer Corra Harris, a native of Elbert County, drew upon her experiences as the wife of a Methodist minister in the mountains of north Georgia to compose her first novel, A Circuit Rider’s Wife (1910).

The tradition of evangelism also manifests itself in several enduring missions of the Methodist church, including education and health care. Involvement in social reforms is another significant aspect of evangelism in the denomination’s history, as many American Methodists participated in the nineteenth-century movements for abolition, prison reform, and temperance. The Salvation Army, founded by a Methodist minister in 1865, is a long-standing example of the denomination’s involvement in mission work.

Origins of Methodism

In 1729, at Oxford University in England, brothers John and Charles Wesley and their associates, including George Whitefield, organized a group to practice a system of faith and discipline within the Anglican Church, which was the official church of England. Because of the methodical way in which this new group approached their spiritual exercises and charitable works, they were labeled Methodists. John Wesley’s emphasis on evangelical preaching created a rift between the Methodists and the Anglican Church, although Wesley did not envision Methodism as a separate church until late in his life.

In 1735 the Wesley brothers and Whitefield sailed to the colony of Georgia, where they served in various capacities. Charles Wesley served as secretary to James Edward Oglethorpe and as chaplain at Fort Frederica on St. Simons Island, while John Wesley served as Anglican rector to the colony. Whitefield was an itinerant evangelist. During their time in Georgia, the three men encountered the Moravians, evangelical Protestants who had also arrived in the colony in 1735. In 1737 the Wesley brothers left Georgia under difficult circumstances and returned to England. After attending a Moravian meeting in London on May 24, 1738, John Wesley recorded in his journal, “I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt that I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me, that he had taken away my sins.” This affirmation of salvation by faith alone became the foundation of Methodist teaching.

As Wesley began to foster the growth of Methodism in England, the Methodist movement in America also grew over the next several decades, partly through the persistent evangelical efforts of Whitefield. The Methodist Episcopal Church, the supreme legislative body of the Methodist denomination in America, was formally organized at a meeting known as the”Christmas Conference,” which was held from December 24, 1784, through January 2, 1785, in Baltimore, Maryland. Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury were ordained as bishops during the conference to organize the work of the Methodist Church in the United States.

Methodist Beginnings in Georgia

The formal introduction of Methodism into Georgia occurred when Coke and Asbury assigned Beverly Allen to Georgia in 1785. Allen was an itinerant minister who had been elected elder at the Christmas Conference and ordained a year later. In 1786 Thomas Humphries and John Major, both of the Virginia Conference, were sent as missionaries to Georgia. Both likely began their work in Wilkes County. Bishop Asbury held the denomination’s first annual conference in Georgia on April 9, 1788, at the fork of the Broad River, about twenty-one miles southeast of Elberton. Ten people were present, including Hope Hull, who was later recognized as the father of Georgia Methodism. In 1790 John Andrew of St. John Parish (later Liberty County), the father of Methodist bishop James Osgood Andrew, became the first native-born Georgian ordained as a Methodist preacher. The Georgia Conference reported 2,294 members in 1790.

The advance of Methodism in Georgia was aided by the interdenominational Second Great Awakening (circa 1790-1830), during which many Georgians converted to evangelical Christianity at outdoor revival services called camp meetings. By 1814 Methodist membership exceeded 10,000, a figure that almost doubled during the next fifteen years. Recurrent awakenings in 1835 and 1858 stimulated further growth, so that 97,000 Methodists lived in Georgia by 1861.

The awakenings quickened interest in missions (foreign and domestic), education, and benevolence. Georgia Methodists actively evangelized among enslaved African Americans and, with the permission of estate owners, established missions on plantations. By the beginning of the Civil War (1861-65), membership among enslaved Georgians had grown to 11,125 in the missions plus thousands more in churches. The total number of African American Methodists, of all denominations, in Georgia increased from 27,385 in 1860 to a reported 75,000 in 1875.

Major Denominations in Georgia

United Methodist Church

The United Methodist Church is the largest Methodist denomination in the state, with roots in the original Methodist Episcopal Church. The history of the denomination is marked by various divisions and mergers, beginning with a separation in 1828 that resulted in the formation of the Associated Methodist Churches. This new denomination was renamed the Methodist Protestant Church in 1830.

In 1844 the divisive issue of slavery led to the creation of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MECS). Congregations in the North, many of which supported the growing abolitionist movement, found themselves at odds with congregations in the slaveholding South. The division occurred at the Methodist Episcopal Church’s General Conference of 1844, when a controversy erupted over the enslavement of African Americans by Georgia bishop James Osgood Andrew, and a resolution was passed asking him to step down. Southern churches, in response, drew up a Plan of Separation, and in 1846 the first General Conference of the newly formed MECS met in Virginia.

A further break within the MECS occurred in 1852, when several Georgia preachers, who had unsuccessfully petitioned the MECS to allow the participation of laypeople in the conference, met in Monroe County and formed the Congregational Methodist Church. This independent denomination, with headquarters in Florence, Mississippi, continues to be active today, primarily in the southern states.

Despite such divisions, in 1861 the Georgia Conference of the MECS retained a clear majority of the Methodists in the state. The MECS remained active during the Civil War, providing chaplains and religious material to Confederate soldiers. In 1876, after the end of Reconstruction, the northern congregations of the Methodist Episcopal Church and the MECS began negotiations for reunification, which continued through the end of the nineteenth century. In 1908 the Methodist Protestant Church became involved in the negotiations as well.

By 1937 the unification plan for the Methodist Episcopal Church, MECS, and Methodist Protestant Church was complete, and all the Georgia conferences approved it overwhelmingly. In 1939 the three denominations united, creating the Methodist Church, as well as the separate Central Jurisdiction for African-Americans.

In 1968 the Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren, which ministered to congregations of German heritage in the mid-Atlantic and midwestern states, merged to form the United Methodist Church. The union took place on April 23, 1968, at the Uniting Conference in Dallas, Texas. The United Methodist Church immediately ordered the dismantling of the Central Jurisdiction and thereby integrated the denomination. In 1988 the North Georgia and South Georgia conferences of the United Methodist Church successfully petitioned the General Conference in 1988 to become separate episcopal areas. As of 2005 the North Georgia Conference had 342,045 members, and the South Georgia Conference had 137,822.

African Methodist Episcopal Church

The AME Church, an independent Black Methodist denomination, established itself in South Carolina in 1863, and by the Civil War’s end missionaries from the denomination had arrived in Georgia to minister to the freedpeople. Founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1816, the AME Church was the first of two Black Methodist denominations from the North to establish itself in the South; the second, AME Zion, arrived in North Carolina in 1864.

During Reconstruction, the denomination continued to grow in the state under the guidance of Henry McNeal Turner, the first AME bishop in Georgia. Historically, the denomination has retained its strong commitment to mission work, and many AME congregations were active in the civil rights movement of the mid-twentieth century. As of 2006 the AME Church in Georgia had 87,884 members.

Christian Methodist Episcopal Church

In 1870 a group of Black Methodist leaders within the MECS gathered in Jackson, Tennessee, and formed the CME denomination. Three years earlier, the MECS had authorized the creation of separate districts for its African American members in the South, but the CME established itself as an entity independent of MECS.

Lucius Holsey, a Columbus native, participated in the CME Church’s organizational meeting and served as the minister of the Trinity CME Church in Augusta. In 1873 he became a bishop in the new denomination and served in that capacity until his death in 1920. Despite the separation of the two denominations, ties between the CME Church and the MECS remained strong for many years, as evidenced by their joint founding of Paine College in Augusta.

During the twentieth century, the CME aligned itself more closely with the AME Church and AME Zion, while distancing itself from the predominantly white MECS. CME members were particularly active during the civil rights moment of the mid-twentieth century, and in 1954 the denomination voted to change its name to the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. The new name became official in 1956. During these years two important civil rights leaders with ties to the CME Church emerged in Atlanta. Attorney and CME member Donald Hollowell represented Martin Luther King Jr. and numerous other civil rights activists in court, while Ruby Doris Smith Robinson credited her upbringing in the CME Church with inspiring her activism in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion

Originally affiliated with the Methodist Episcopal Church, AME Zion was organized in 1821 in New York City and severed ties with the Methodist Episcopal Church two years later. In 1864 AME Zion arrived in the South, establishing itself in North Carolina under the leadership of James Walker Hood, who was elected bishop in 1872. The following year the AME Zion General Conference established the Louisiana Conference, which included Georgia and all other states south of North Carolina.

After the war the denomination continued to recruit new members from the African American communities in the southern states. In 1867 Georgia was designated as a separate conference, and in 1885 the North Georgia Conference was organized by Bishop Thomas Henry Lomax, who had earlier served with Hood in North Carolina and was elected bishop in 1876.

Along with the AME and CME churches, AME Zion congregations were active in the civil rights movement of the mid-twentieth century. The three denominations continue to maintain strong ties with one another in the twenty-first century.

Education and Missions

During the antebellum years Georgia Methodists were particularly interested in education. In 1834 the Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church established the Manual Labor School, the forerunner of Emory College and Emory University in Atlanta. Georgia Female College in Macon was acquired by the Methodists in 1836 and renamed Wesleyan Female College in 1843 and Wesleyan College in 1917. Andrew College, now a junior college, was chartered in 1854 in Cuthbert for the education of women. LaGrange College, another institution for educating women, was purchased in 1857 by the conference.

Methodists continued their traditional support for education after the Civil War by establishing several of the state’s institutions of higher education, including colleges for African Americans. In 1869 the Freedman’s Aid Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church founded Clark College (later Clark Atlanta University) in Atlanta; Clark’s theological department became Gammon Theological Seminary in 1880. The AME Church chartered Morris Brown College in 1881, and a third historically Black institution, Paine College in Augusta, was organized jointly by the MECS and CME in 1884. Two schools also opened in the Georgia mountains: Reinhardt Academy (1883; later Reinhardt University) in Cherokee County and Young Harris College (1886) in Towns County.

The welfare of children, another historical concern for Georgia Methodists, led to the founding in 1871 of the Orphan’s Home (later United Methodist Children’s Home) in Norcross, and in 1873 of the South Georgia Methodist Home for Children and Youth in Macon. Other projects undertaken in the early twentieth century included the Vashti Center (1903) in Thomasville, the Ethel Harpst Center (1914; later Murphy-Harpst) in Cedartown, and Camp Glisson (1927) in Dahlonega.

Both traditionalists and modernizers emerged among Georgia Methodists toward the end of the nineteenth century. Atticus G. Haygood, editor of the Wesleyan Christian Advocate in the late 1870s, is perhaps the best representative of the progressive wing. Elected bishop of the MECS in 1882, he declined consecration but later agreed to serve when he was reelected in 1890. Haygood favored the church’s political involvement (once anathema), education for African Americans, federal aid to public education, and philanthropy. The progressives’ support of education was exemplified by Warren Akin Candler, who became a bishop in 1898, and his brother Asa Candler, who founded the Candler School of Theology in Atlanta in 1914. The school was named for Bishop Candler, its first chancellor, and the following year it became part of the newly formed Emory University. Methodist evangelist Sam Jones, on the other hand, epitomized much that traditionalists held dear in his preference for straightforward preaching against sin over theological discussions.

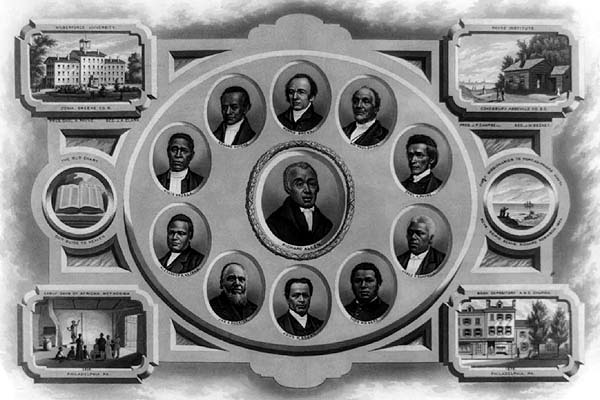

Methodists’ commitment to health care led to the opening in 1905 of Wesley Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Ownership of the hospital was transferred to Emory University in 1922. The Warren A. Candler Hospital (later the Candler General Hospital), located in Savannah, was acquired by the MECS in 1930, and in 1944 Emory University acquired the Crawford W. Long Memorial Hospital.

From 1944 to 1948 the Methodist Church promoted the “Crusade for Christ” to reinvigorate Methodism. In Georgia this campaign prompted interest in improving education for African American ministers. The Interdenominational Theological Center was formed in 1958 as a consortium of Gammon Theological Seminary (Methodist Church), Phillips School of Theology (CME), and Turner Theological Seminary (AME Church), as well as theological schools of other denominations. Since 1985 the Interdenominational Theological Center has served as an example to and provided a location for meetings of the Commission on Pan-Methodist Cooperation and Union.

In 1956 the Methodist Church, a longtime advocate of education for women, authorized the ordination of women. In 1959 Ruth E. Rogers became the first full member of the North Georgia Conference, and Marcia Cochran and Allison Morgan became full members of the South Georgia Conference in 1978.

Missions, education, and benevolence, all foundational Methodist priorities, continue to be supported by Georgia Methodists in the twenty-first century.