As the nation’s top producer of peanuts, Georgia is closely associated with the crop both economically and historically. In 2007 peanuts generated a farm gate value (the value of a crop when it leaves the farm) of $382 million, ranking it seventh in the state’s top commodities for that year. (Poultry was ranked first, with a farm gate value of more than $4.8 billion, and tobacco was twenty-seventh, with $65 million.)

Peanut farmers in Georgia and elsewhere have turned to the field of genetics to help advance the peanut industry’s profitability through better breeding and trait selection. In a process known as genetic crossing, or hybridization, researchers have bred peanut plants that allow farmers to produce higher-yielding crops with qualities desired by the public.

The Hybridization Process

Hybridization is the combination of deoxyribonucleic acid (commonly known as DNA, the genetic material of an organism) from two different species of plants to produce a new generation of plants with a desired trait, such as increased tolerance to stress or heat. The hybrid seed will possess traits from both parent plants, creating a new, distinct breed. Plant hybridizers have determined that the best environment for producing hybrids is a hot and humid climate, which makes Georgia greenhouses ideal growing locations.

The National Peanut Research Laboratory (NPRL) in Dawson (in Terrell County) uses hybridization to cultivate peanuts with high oil content, drought tolerance, and resistance to tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), a disease affecting crops grown in temperate and subtropical climates. The NPRL takes DNA from these hybrid peanuts, copies the DNA thousands of times, and locates long segments of DNA that may contain a gene encoding for a particular trait. These long DNA segments are replicated and inserted into the peanut genome to breed new peanut varieties. In Georgia, the plants are hybridized during late June and early July.

Peanut Research in Georgia

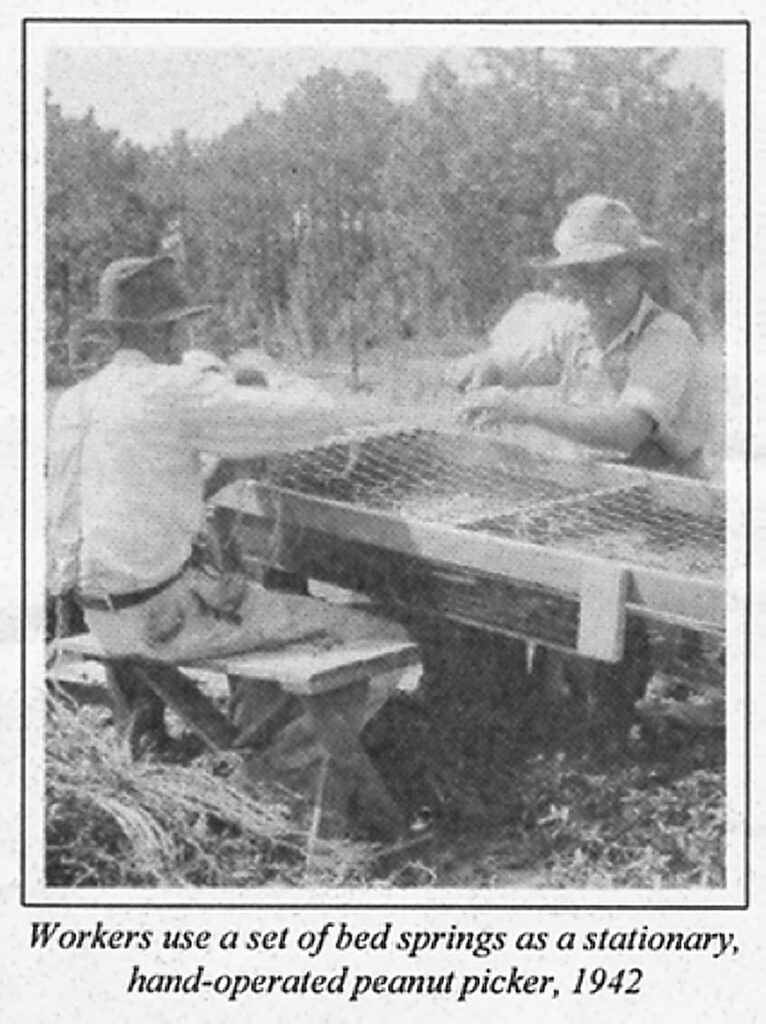

Historically, the association between Georgia and peanuts began for many Americans when Jimmy Carter, a Sumter County peanut farmer, became president of the United States in 1976. But the historical connections reach back even further. Naomi Chapman Woodroof, one of the first two women in the country to earn a degree in agriculture, performed groundbreaking research on peanuts at the Coastal Plain Experiment Station (later University of Georgia Tifton campus) from 1933 to 1967. Another scientist at the Tifton station, James L. Shepherd, developed the first mobile peanut combine machine during the early 1970s, and the Georgia Museum of Agriculture and Historic Village (formerly the Georgia Agrirama), also in Tifton, was built to house his invention. UGA’s Georgia Experiment Station in Griffin holds a repository of more than 84,400 germplasm samples, many of which are peanut samples, in its Plant Genetic Resources Conservation Unit, maintained by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The germplasm is available to scientists worldwide for use in breeding new crop varieties.

Courtesy of Jane Woodroof Akers

In the twenty-first century, scientists at the Coastal Plain Experiment Station are researching ways to produce a hypoallergenic peanut, or a peanut that will not provoke an immune response. A peanut allergy affects the human immune system’s ability to recognize a nontoxic food protein, and may cause hives, dizziness, swelling of the throat, and even death. The Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 requires food manufacturers to label products with the words “contains peanuts” if peanuts are present in any amount, or to indicate if the food is processed in the presence of peanuts. But these safeguards do not prevent all accidental peanut consumption.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Peanuts contain eleven known allergenic proteins, and removing these proteins may produce a hypoallergenic peanut. The genes that encode for these proteins can be intentionally mutated, and even a single change in the DNA sequence can dramatically lessen the allergenic effects. Mutations, or errors in DNA replication, can be detected using a special enzyme that locates mismatched genetic material. If these mutations produce peanuts that do not trigger the allergy immune response, the sequence of mutated DNA can be inserted into the normal peanut genome, creating the hypoallergenic peanut.

Environmental Obstacles

Peanut plants are vulnerable to pests and diseases that threaten to destroy crops, and fungi in particular are a major health concern for farmers. The ongoing research to develop hypoallergenic peanuts raises concerns for some about the side effects of these genetic modifications, including the peanut plants’ decreased resistance to toxin-producing fungi. Of particular concern are the common molds Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus, both of which produce a toxic and carcinogenic substance known as aflatoxin. Peanuts and peanut products, as well as milk, figs, and corn, must be tested for aflatoxin before being distributed, since the mold is invisible to the naked eye. Researchers at both the NPRL and Coastal Plain Experiment Station are investigating ways to combat aflatoxin contamination.

Another disease affecting peanuts is TSWV, which has become more common in Georgia since 1986. The virus is transmitted through small, winged insects called thrips, which feed on crops and pass on the disease. Infected plants wilt and die, causing large losses in crop yield. TSWV is difficult to control because it affects a variety of hosts, including peanuts, vegetables, and weeds. To battle this disease, growers in Georgia hybridize crops to be resistant to TSWV and monitor the occurrence of weeds in the croplands.