Since the early nineteenth century the circus has been a favorite form of professional entertainment for Georgians. The circus first appeared in America in 1793, and Georgia hosted a circus as early as 1801 in Savannah.

Just like circuses of today, these early shows emphasized horseback riding, acrobatics, and clowning. The circus’s appeal in Georgia from the early nineteenth century to the present day provides a window into how southern tastes in popular culture and southern norms of public behavior have changed over time.

The Antebellum Circus

The early circus was strictly an urban amusement. Circuses performed in a single city for weeks at a time, playing in theaters or temporary wooden structures built by the showmen. In a coastal state such as Georgia, shows moved from city to city by riverboat, and before 1825 no circus played farther west than the state’s short-lived capital of Louisville. But that year the introduction of a portable canvas tent into the circus business allowed shows to undertake more frequent and ambitious moves deep into the Georgia backcountry. With the addition of small towns to their itineraries, performers and workers now faced the exhausting task of moving on rutted and muddy country roads from one isolated Georgia community to another. Circuses reached the interior towns of Athens, Macon, and Milledgeville by the late 1820s and Columbus by the early 1830s, giving rural Georgians the opportunity to see the same performances that their urban counterparts had enjoyed for years.

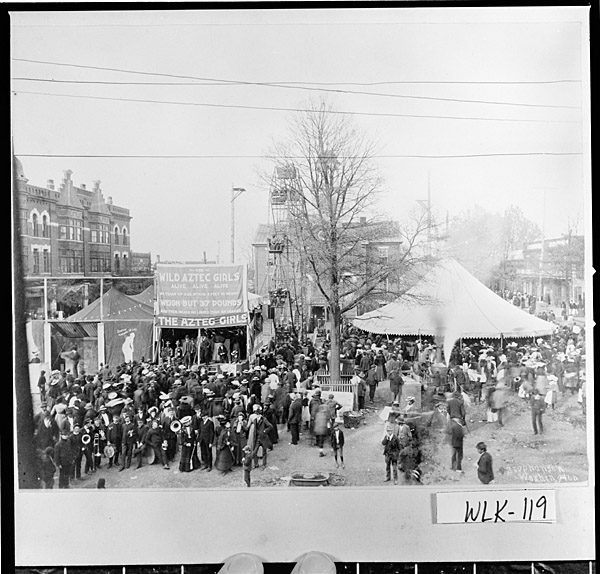

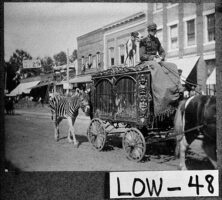

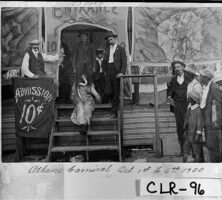

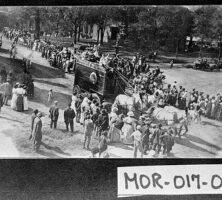

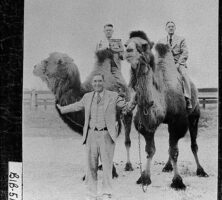

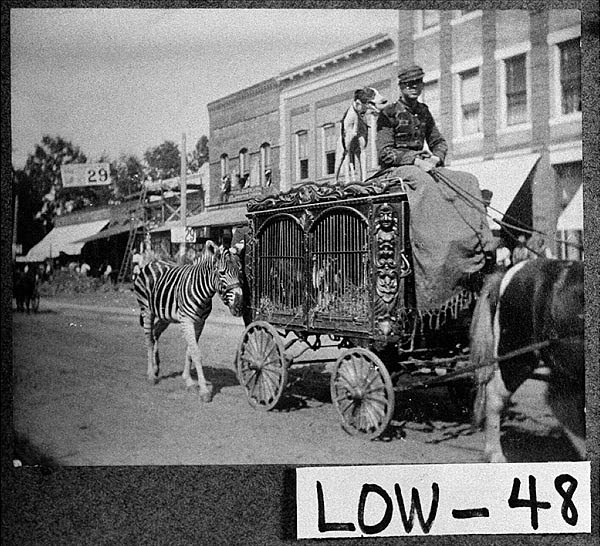

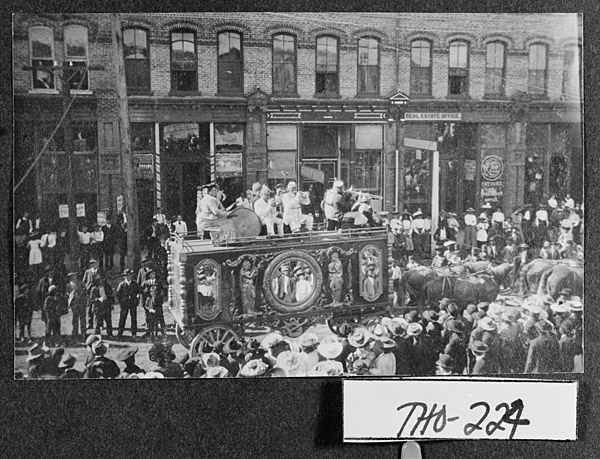

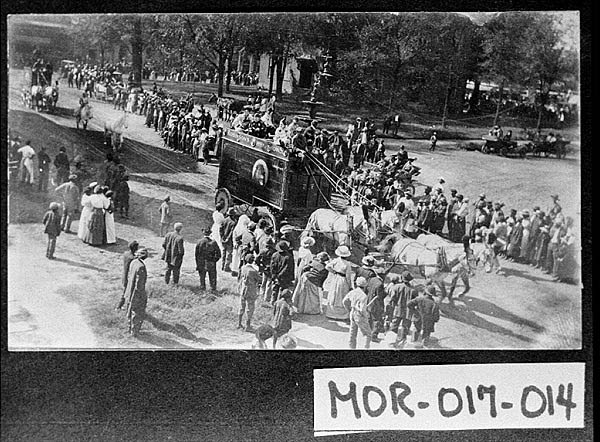

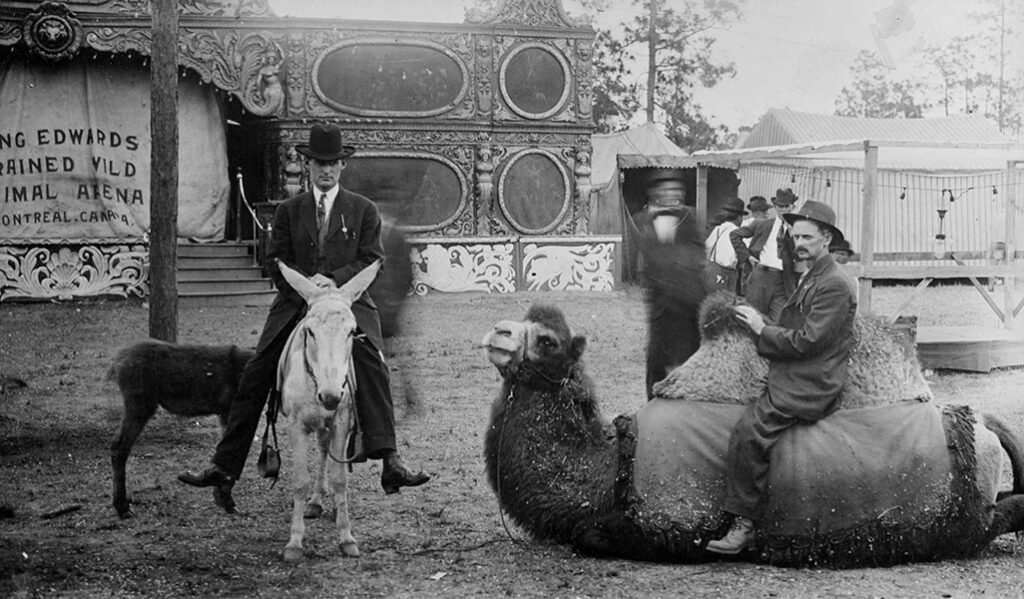

These shows featured entertainment sure to fascinate rural and small-town southerners: the display of handsome steeds, skilled riding, exotic animals, and demonstrations of human strength and athleticism. But troupes also included risque acts like scantily dressed female equestrians and ribald clowns, all performing within the confines of a single ring. Despite, or perhaps because of, these racy features, the appearance of circus posters on fences and barns in remote Georgia hamlets brought hundreds of people of all classes and colors to town on show day. Once there, they lined the main thoroughfare to watch the circus parade before crowding under the canvas for the big show.

The diverse character of circus crowds prompted showmen to provide tented accommodations consistent with southern hierarchies of class and race. Circuses invariably attracted rowdy young men who viewed circus day as an occasion to drink, carouse, and fight, often with equally unruly circus roustabouts. Free and some enslaved African Americans also came out for these shows. Consequently, antebellum circuses offered special reserved seats for well-to-do white families. Lower-class whites, African Americans, and the occasional prostitute watched the show while standing in the “pit,” the part of the tent that lacked seats. The pit was segregated, with whites on one side and Black viewers on the other. Circuses would continue to provide spectator areas segmented by class and color well into the twentieth century.

The dangerous combination of disorderly men and morally questionable entertainment prompted evangelical leaders and class-conscious elites to denounce the circus. For instance, the Methodist Book of Discipline proscribed circus attendance for church members until the twentieth century. The faculty of the University of Georgia in Athens deemed the circus an immoral entertainment and forbade students to attend such shows. Newspaper editors routinely condemned the ribald character of circus entertainment and the rough crowds that gathered to enjoy it. Such criticisms discouraged many respectable men and women from entering the tents of these traveling shows. To rebut the critiques of the circus as sinful and plebeian, showmen argued that their menageries displayed the wonder of God’s creation and promised that their programs would not offend even the most scrupulous individuals.

The Golden Age

The Civil War (1861-65) drove circuses out of Georgia, but they returned to the state in the fall of 1865. Almost all nineteenth-century shows were based in the North, but some attempted to win the favor of southern audiences by adding “Great Southern” or “New Orleans” to their titles, while spotlighting any southern members of their troupes. During these years Georgia did produce a short-lived show of its own. In 1871 an enterprising Atlanta stable owner and a prominent showman organized the Haight and Wooten Circus, which featured many southerners among its performers and staff. Haight and Wooten split as a team in 1872, and Haight formed a new circus, the Great Eastern Circus, which for many years toured not only Georgia and the Southeast but also the rest of the nation and Canada.

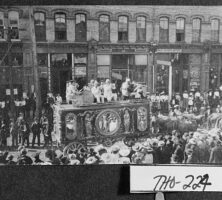

The 1870s also saw a shift from wagon to rail transport, which soon made size a more important circus attribute than sectional allegiance. Although in 1838 Georgia was the site of the earliest known use of a railroad by a circus, the industry did not fully embrace rail travel until 1872. Once on rails, a circus could move more equipment, men, and animals than ever before. Showmen expanded their circus tents from one ring to three, allowing seating capacities to grow from hundreds to thousands. These changes helped the circus become the nation’s most popular form of entertainment during the late nineteenth century.

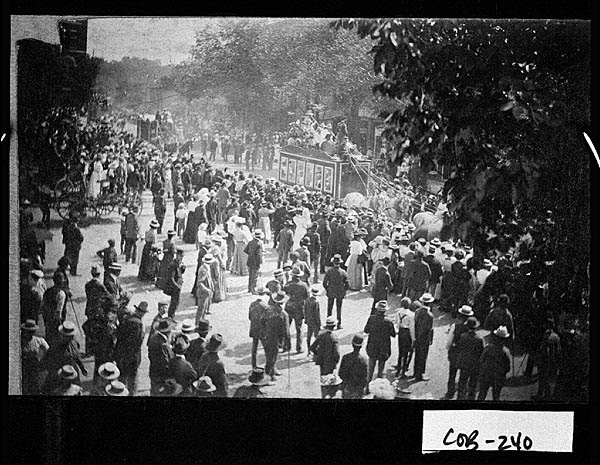

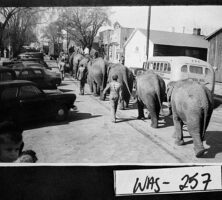

The use of railroads by shows also altered the social nature of circus day. Movement by wagon had meant that a small town was as likely to get a leading show as a big city. But movement by rail confined the top troupes to the growing towns and big cities along railroad lines. For rural Georgians the journey to see the circus was now as much a part of the circus-going experience as the show itself. Farmers and their families left home hours and sometimes days before a show and traveled to large towns and cities on foot, on horse, by wagon, and by excursion train. Upon arrival the country people joined with town-dwellers of all classes and colors to create huge circus crowds. The varied members of these throngs socialized, drank, fought, laughed, and generally celebrated a release from the day’s labor. By the 1880s most Georgia merchants and community leaders welcomed the circus because country people spent large sums in local stores and eateries before and after they attended the show.

Georgia’s African Americans particularly embraced the circus and the attendant activities of circus day. Early in the morning ambitious Black Georgians erected “snack stands” near the circus grounds to vend edibles to circusgoers of both races. These booths also served as central locations for African Americans to congregate and mingle during the course of the day.

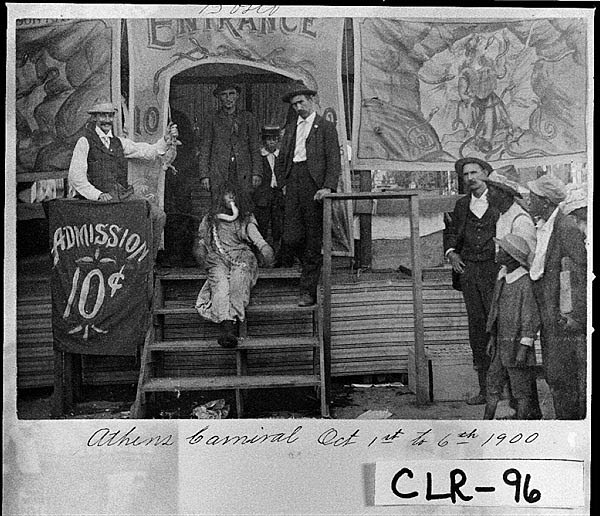

For persons of more limited means, magnificent circus parades provided free entertainment even if they could not afford a ticket to the show. But perhaps the most attractive aspect of the circus-day experience for African Americans was the limited segregation practices employed by showmen. On the circus lot, Black and white patrons stood in the same ticket line, entered through the same main gate, and mingled together in the same open viewing areas of the sideshow and menagerie tents. In fact, circus managers divided the races only under their big tops. They did so by confining African Americans to general admission seats located at one end of the arena; African Americans who patronized the theater, in contrast, found themselves forced to enter through the playhouse’s rear entrance before being relegated to the worst seats in the house, typically in the balcony’s “Negro gallery.” The limited application of Jim Crow practices, when joined with the day’s festive atmosphere, produced consistently heavy Black turnouts at circuses.

Despite circus day’s carefree ambiance, tented outfits remained magnets for immoral activities and dangerous situations. Rigged gambling games became a regular sideshow feature. Violence was another problem. Fueled by liquor, Georgia men stabbed, shot, and murdered each other at circuses with bloody frequency. Several circus men also lost their lives in violent confrontations with Georgia toughs. In 1881 a riot broke out in Cartersville between show employees and local ruffians.

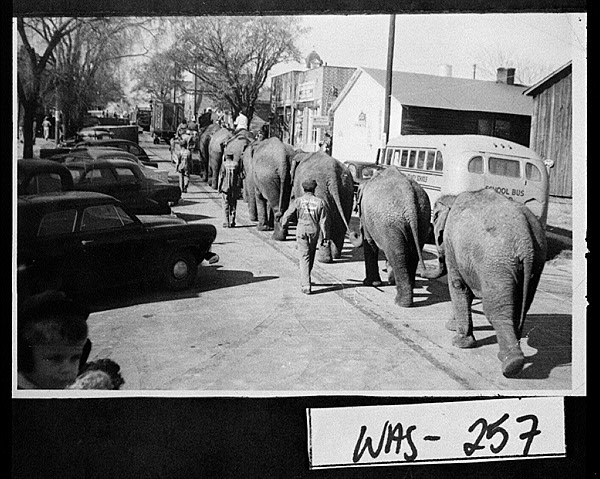

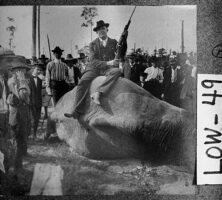

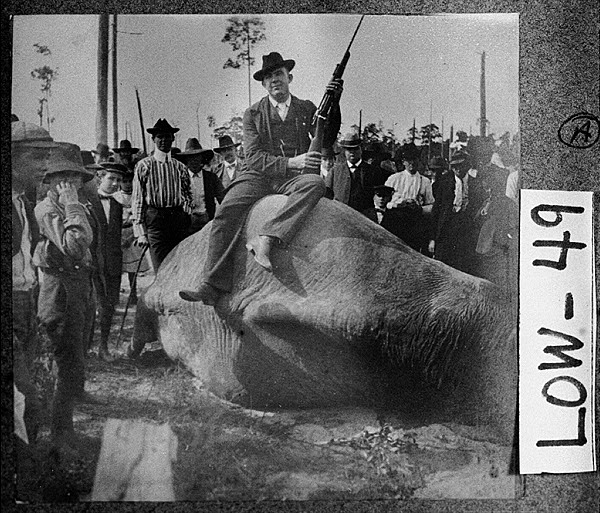

Humans were not the only source of mayhem at Georgia shows. A circus elephant rampaged in Valdosta in 1902, killing one man and leaving the town terrified until the chief of police dispatched the pachyderm with a high-powered rifle. Yet not all memorable animal incidents led to such unhappiness. In 1889 an Atlanta businessman purchased the menagerie of a bankrupt circus and donated it to the city’s Grant Park. This group of animals became the basis of Atlanta’s first zoo (later Zoo Atlanta).

The Twentieth-Century Circus

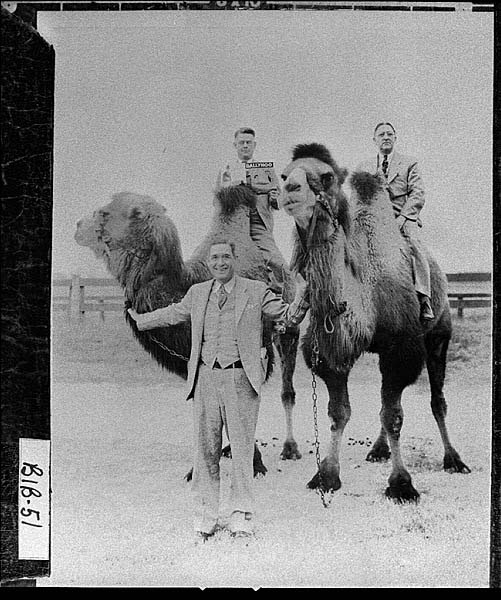

By the early twentieth century the circus had entered a period of decline. Novel forms of entertainment like movie houses, amusement parks, and professional sports competed with circuses for the attention of the Georgia public. The ever-increasing number of automobiles on the road forced shows to end the long and popular tradition of the free circus parade. Still, Georgia residents could point with pride to the fine shows that called the state their winter home. Between 1908 and 1956, Macon’s Central City Park hosted five different circuses. Other Georgia cities where circuses wintered during the first half of twentieth century include Americus, Atlanta, Augusta, Savannah, and Valdosta.

Modern Circus

Since the 1990s smaller shows like Barnum’s Kaleidoscape and Cirque du Soleil have spearheaded a popular resurgence of the circus in America. Georgia’s contribution to this new generation of tented troupes is the Black-owned UniverSoul Circus, which debuted in Atlanta in 1994. This one-ring show offers standard circus acts like clowning, acrobatics, and performing animals but presents them with a distinctive African American aesthetic. Breaking with circus conventions, UniverSoul performers dance to the beat of rhythm and blues, salsa, and hip-hop, and its clowns draw on the realities of urban life for their humor. Yet in a return to the intimacy and interactivity of the antebellum circus, the show brings audience members into the ring to dance and sing. Through its fusion of tradition and innovation, the UniverSoul Circus demonstrates why the venerable entertainment institution of the circus will remain a part of Georgia’s, and the nation’s, cultural fabric.