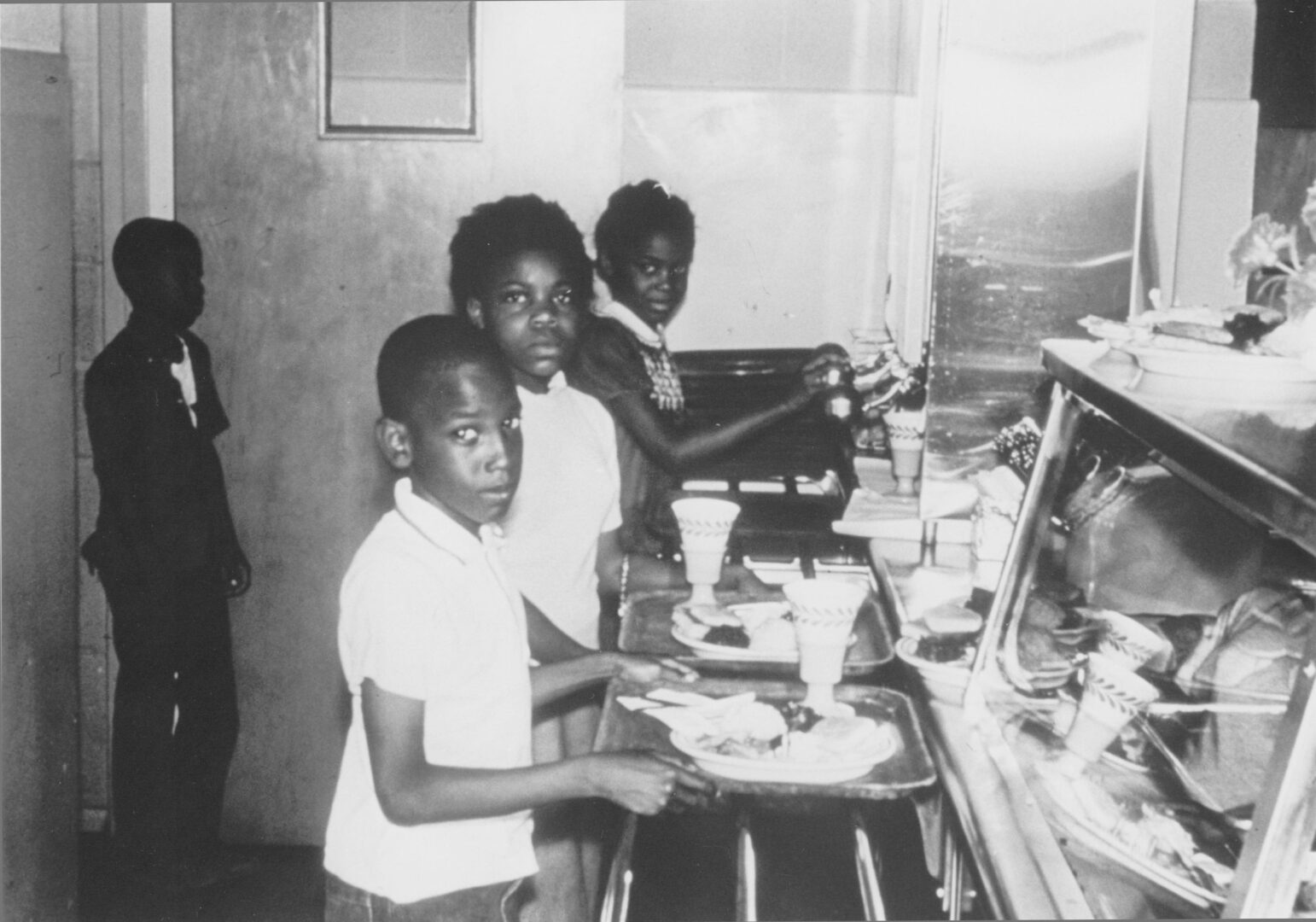

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries

Food, Power, and Politics: The Story of School Lunch

The National School Lunch Program affects millions of students and has a connection to nearly every U.S. family. The story behind this initiative is one of twists and turns, as the program evolved to meet the changing needs of children, politicians, and corporate interests.

Introduction

The National School Lunch Program affects millions of students and has a connection to nearly every U.S. family. What began as a way to strengthen the nation through better nutrition for schoolchildren in 1946 soon became a complicated program administered by local, state, and federal partners, all with competing interests. The story behind this initiative is one of twists and turns, as the program evolved to meet the changing needs of children, politicians, and corporate interests.

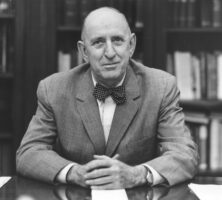

Food, Power, and Politics: The Story of School Lunch examines the complicated past of the National School Lunch Program, with a focus on people and events in Georgia. This exhibition was developed in 2014 by the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies at the University of Georgia in celebration of the library’s fortieth anniversary. U.S. senator Richard B. Russell Jr. authored the original legislation establishing the National School Lunch Program and ensured its passage through both houses of the U.S. Congress. He often said that the creation of this program was his proudest accomplishment during his long career in the U.S. Senate (1933-71).

Early Efforts and False Starts

The school lunch movement first emerged in Europe in the late nineteenth century. Great Britain and Germany implemented the most extensive feeding programs alongside other benevolence efforts, such as the distribution of clothing and textbooks, under centralized oversight from national governments. Taking a cue from these early European efforts, experimentation with school lunch in the United States began during the Progressive Era, a period of social reforms occurring in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Religious institutions, charities, and professional women’s groups, including the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union and the Women’s School Alliance, launched the first free milk and lunch programs to combat pervasive childhood malnutrition in the growing urban centers of the Northeast and Midwest.

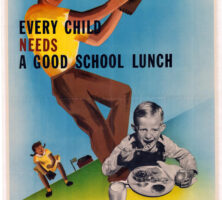

Supported by the new field of nutrition science, which sought to standardize diets and expose the dangers of malnourishment, Progressive reformers maintained that a “full belly” contributed to a more positive learning environment in schools. They argued that well-fed students, especially those from poor or immigrant households, would be more likely to embrace middle-class ideals and appreciate American democratic institutions if they were guaranteed regular hot meals. Despite the best of intentions, however, these largely local and unstandardized programs had limited success.

For most school administrators, the financial risks associated with providing free lunches to growing numbers of children often outweighed the perceived benefits of such programs. Schools in rural America, especially the South, lagged behind in developing their own programs owing to a lack of money, facilities, personnel, and public will. Because the regional economy depended largely on agricultural products and unskilled labor, few leaders in state governments saw much reason to invest further in costly schools.

Throughout the Progressive Era, most Georgians continued to live in rural areas and make their living as farmers. Many also lived in poverty. By 1920 two-thirds of the state’s farmers worked land they did not own, often as sharecroppers. In these circumstances, rural parents often opposed mandatory school terms and preferred to keep family members at home to help work on the farm. Systematic, statewide school reform in Georgia would only come later, in the mid-twentieth century, as the state shifted toward a more urban economy.

Nutrition and National Security

By the early 1930s, with the United States entrenched in the Great Depression, many children were coming to school hungry. In response, communities across the nation implemented local school lunch programs, typically funded by charitable organizations and state tax dollars. In DeKalb County, for example, social activist Frances Pauley worked with public health professionals to create a hot lunch program in the county’s schools.

As the decade continued, new motivations emerged for supporting a school lunch program with joint state and federal funding. During this period of economic distress, the federal government sought to supplement farm incomes by stabilizing commodity prices. At the same time, drastically reduced consumer demand resulted in surpluses of food crops. Under U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program, proposed legislation advocated not only for providing school lunches but also for managing these surplus commodities.

In 1933 the Roosevelt administration began disbursing donations of surplus commodities via several New Deal agencies, first through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and later through the Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation (FSCC) and the Surplus Marketing Administration (SMA). Much of this surplus food was donated to local school lunch programs, and in 1935 the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and National Youth Administration (NYA) supplemented these efforts by offering funding and training for cafeteria workers throughout the country. By 1941 more than 2.3 million students in the South were participating in the SMA’s school lunch program, significantly more than in any other region of the country.

U.S. participation in World War II (1941-45) reshaped federal support for local lunch programs as rising food and labor costs forced cuts in lunch service. Concerned about a national epidemic of malnutrition, which compromised the health of military troops as well as civilian workers and children, Congress authorized funds in 1943 to create the Community School Lunch Program, in which local schools received limited federal funding to provide food and school nutritionists. Other costs, such as building cafeterias and maintaining a professional food-service staff, were not covered, leaving many communities unable to participate. Meanwhile, local oversight for participating communities was often lax and did not always adhere to federal standards for equitable distribution of food regardless of students’ race or socioeconomic status.

Debating the National School Lunch Program

At the end of World War II, proponents of maintaining and expanding school lunch programs worried that the federal government’s ad hoc funding schemes discouraged local school districts from participating. Many districts were reluctant to invest in constructing cafeterias and purchasing kitchen equipment without guaranteed federal funding. Southern Democrats, meanwhile, bristled at the suggestion of federal oversight for school lunch programs and demanded continued local control.

As a longtime politician and former governor of Georgia, U.S. senator Richard B. Russell Jr. was intimately aware of agriculture’s importance to the economy of his home state. A vocal supporter of federal agricultural assistance and early efforts to subsidize school food and nutrition programs, Russell saw a national school lunch program as a way to improve the diets of hungry children and provide a continual outlet for southern crops. Passing such legislation, however, proved to be an uphill battle marked by vigorous debates among politicians, nutritionists, educators, farmers, and civil rights advocates.

First proposed in 1943, the original draft of the National School Lunch Act met resistance from both fiscal conservatives and states’ rights advocates. Some—like Malcolm Tarver, a U.S. representative from Georgia—likened the legislation to creeping socialism at best and communist indoctrination at worst. By 1944 disagreements also arose between those who believed that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) should administer the program and those who advocated oversight by the U.S. commissioner of education—a power struggle that continued well into the late twentieth century. But perhaps the most contentious debate focused on how the program would be implemented in segregated southern schools. Once enacted, the program would require participating schools to operate lunch programs on a nondiscriminatory basis while following federal nutritional standards and utilizing surplus commodities.

Passage of the National School Lunch Program

In February 1946 Richard B. Russell Jr. introduced to the U.S. Senate a “compromise bill,” which he wrote in hopes of satisfying a national school lunch program’s many competing interests. Russell and his colleague Allen J. Ellender of Louisiana, both in key positions on the Senate Agriculture Committee, steered the legislation through Congress.

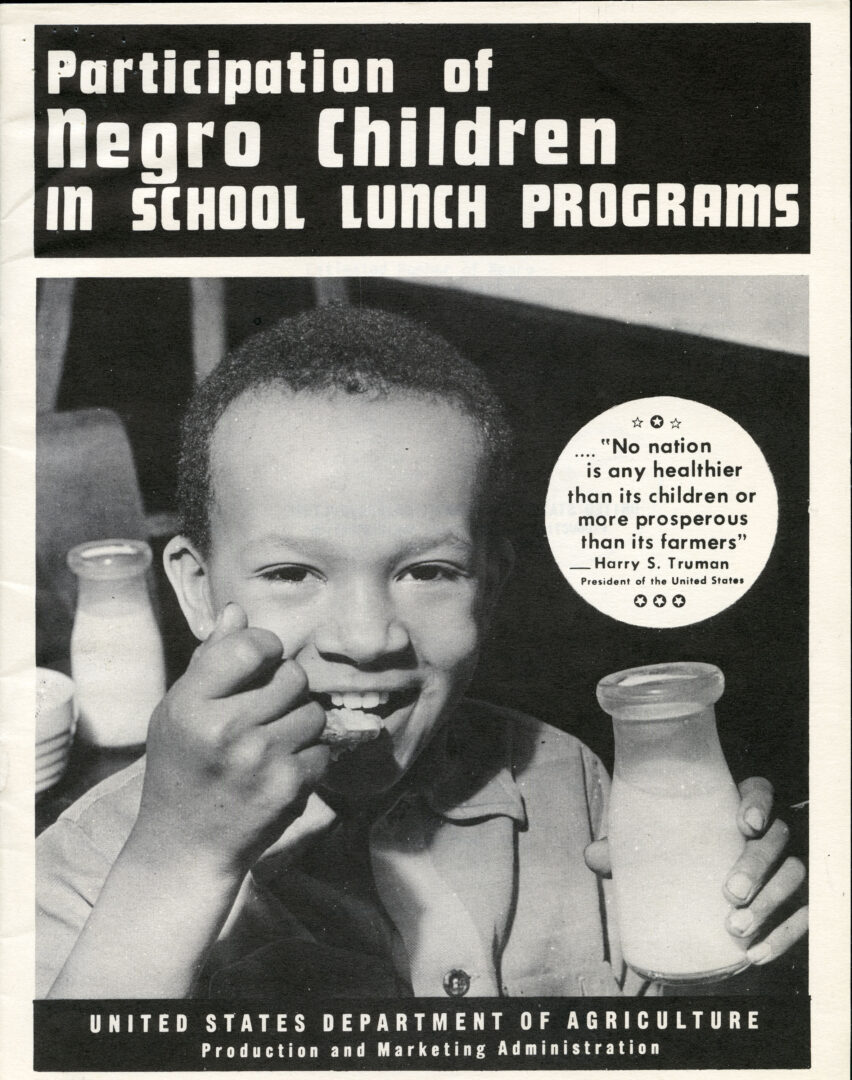

When the bill reached the U.S. House of Representatives, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. proposed an amendment that would deny federal funds to any state or school system that practiced racial discrimination in its operation of the lunch program. This amendment was the first of many antidiscrimination riders that Powell, an African American representing the predominantly Black neighborhood of Harlem in New York City, would introduce to legislation during his long tenure in Congress. Many southern lawmakers recognized the measure as an attempt to undermine Jim Crow customs, but most believed, as Powell himself admitted, that it did not go far enough to end segregation. Although passed by Congress, the amendment remained a largely symbolic gesture that was not properly enforced and so failed to prevent discrimination in school food service.

Both houses of Congress finally passed the National School Lunch Act after careful redrafting and with support from the aging New Deal political coalition, a fragile alliance between the liberal and conservative wings of the Democratic Party. The stated dual goals of the program were “to safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities.” U.S. president Harry Truman signed the act into law on June 4, 1946.

Although participation in the program remained optional, schools that accepted federal funds were obliged to abide by several guidelines. These requirements included agreeing to operate the lunch program on a not-for-profit basis, maintaining accurate records of all purchases and sales, and submitting regular reports to the designated oversight agency in each state. Additionally, the meals served at participating schools had to incorporate as many surplus agricultural commodities as possible and adhere to dietary guidelines outlined by the USDA.

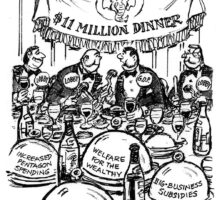

Early Commodities in School Lunch

The National School Lunch Act of 1946 mandated that all participating schools abide by certain nutritional standards while also utilizing surplus agricultural commodities. As a result, early school lunches included such staples as poultry, beef, and dairy products. The program offered producers of these commodities access to a new, highly lucrative market. In times of relative prosperity, school lunch enhanced farm profits; in economic downturns, it provided a buffer when consumer purchasing power dropped. Eventually special interest groups like the American Dairy Association and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association began lobbying for the incorporation of their products into school lunches nationwide.

Two particularly important commodities to Georgia’s economy held a prominent place in the school lunch program: poultry and peanuts. The pioneering efforts of Jesse Jewell, who revolutionized the poultry business in Gainesville from the 1930s through the 1950s, made Georgia a leading producer of chicken and eggs. School nutritionists considered chicken to be a good source of lean protein and a low-fat, low-cost alternative to beef and other meat products. As one of the top poultry-producing states in the nation today, Georgia farmers continue to profit from chicken’s prominent place in the National School Lunch Program.

Peanuts also emerged as a major crop in the state during the 1930s and 1940s, when farmers in south Georgia transitioned away from cotton after years of declining prices and boll weevil infestations. The cash crop became more lucrative by midcentury as peanut butter grew in popularity with U.S. consumers. Rich in protein, essential nutrients, and calories, peanut butter satisfies several USDA nutritional guidelines. Peanut growers sought to incorporate their produce into the National School Lunch Program from the outset, even recommending in the 1950s and 1960s that peanut butter be used as a replacement for butter and margarine in school lunches.

Chicken farmers, peanut growers, and their representatives in government continue to lobby the USDA intensely today for surplus commodity designation as well as prime placement in school meal offerings.

The School Lunch Mandate

Poverty as a national problem rose to prominence in the early 1960s. Under the direction of Secretary Orville Freeman, the USDA commissioned a survey to assess the effectiveness of the National School Lunch Program. Findings revealed that only a small number of schools were providing free or reduced-price lunches and that the participating schools were typically those demonstrating the least need. Such schools had the required food-preparation facilities and, more importantly, a large population of students able to purchase full-price meals. Schools in high-need areas—such as those in inner-city neighborhoods and rural districts—lacked adequate facilities and staff.

Several amendments to the National School Lunch Act in 1962 sought to improve the underrepresentation of low-income participants in the program. However, Congress did not appropriate additional funding to make these reforms a reality until the passage of the Child Nutrition Act (1966), which expanded institutional eligibility and enacted a pilot breakfast program. The consequences of making good on the mandate would steer the program into uncharted territory during the following decades, as school lunch transformed from a farm subsidy into an antipoverty program.

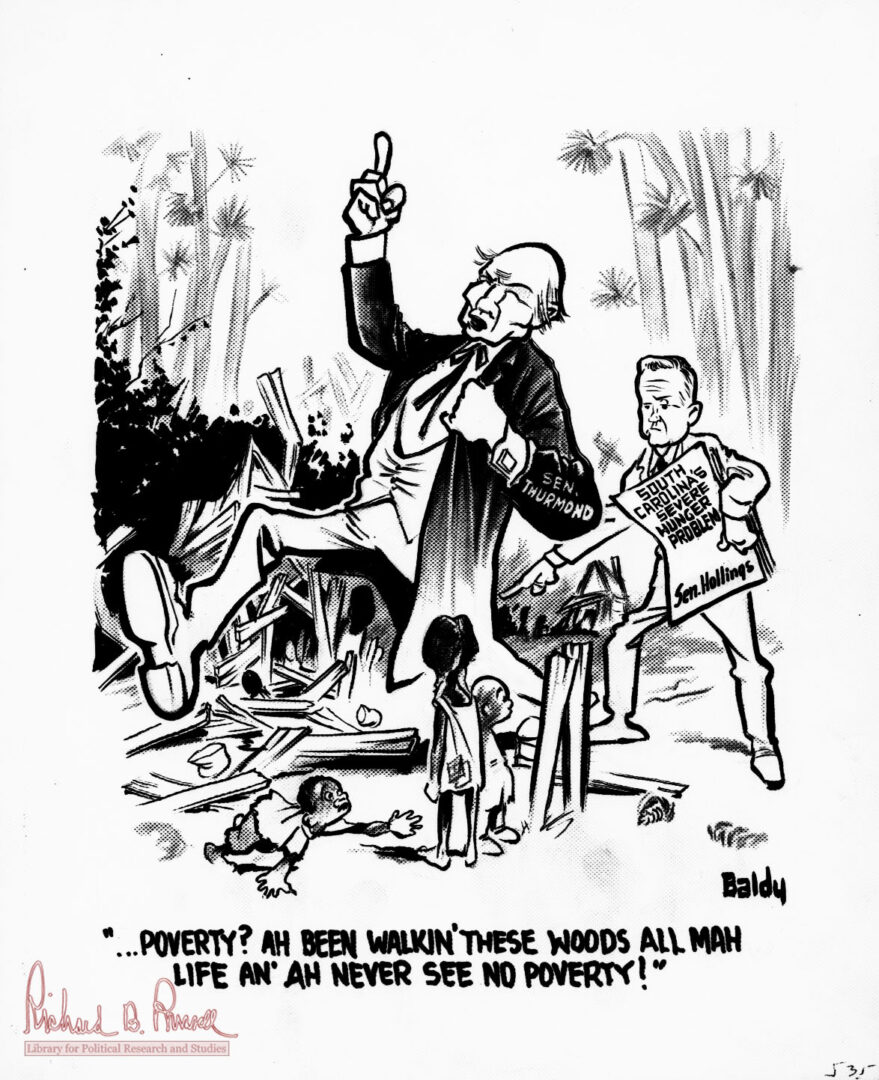

U.S. senator Herman Talmadge of Georgia was a longtime advocate for the expansion of the school lunch program. In 1969 school lunch administrators accompanied Talmadge on a high-profile “hunger tour” through middle Georgia and Atlanta in an attempt to investigate the state’s mounting food crisis. Over two days the party visited urban and rural schools in which many children struggled with hunger and malnutrition. Similar tours were conducted in other states, including neighboring Florida and South Carolina.

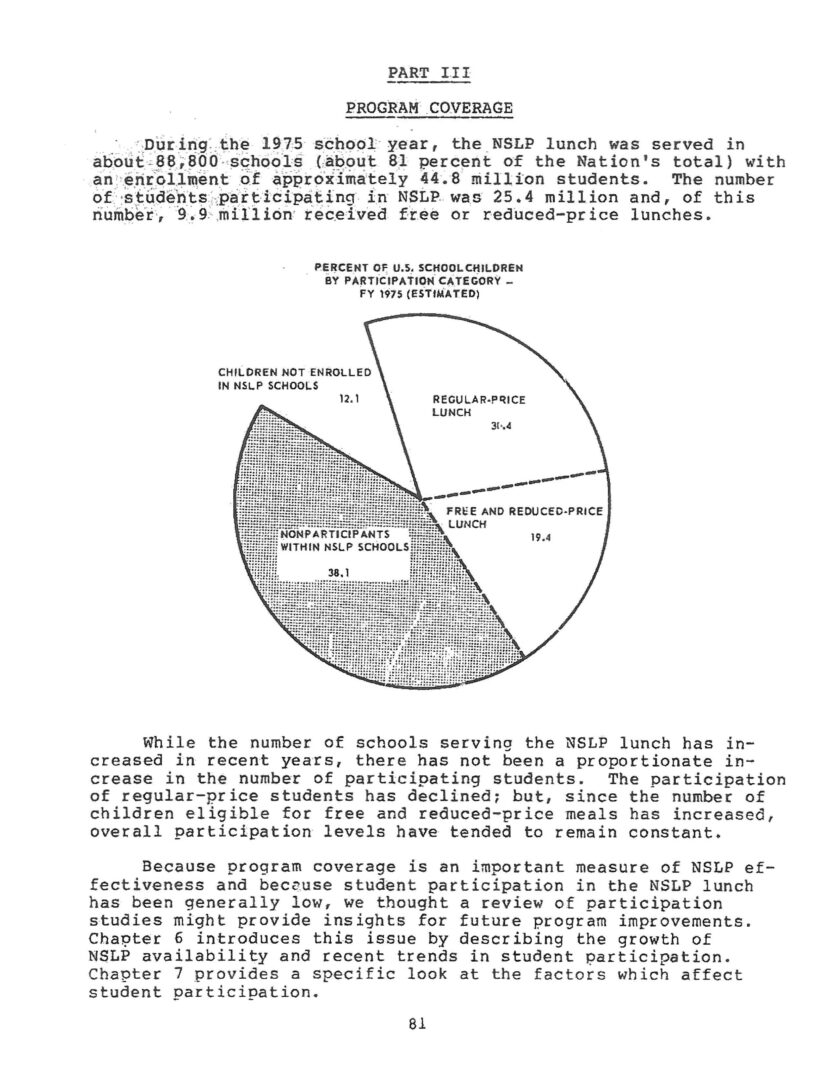

The tour shaped Talmadge’s determination to support the National School Lunch Program, which he deemed an “effective weapon in efforts to break the poverty and welfare cycle.” Soon thereafter he wrote amendments to overhaul the original 1946 legislation, which Congress passed in 1970. The USDA Food and Nutrition Service administered the revised school lunch program, updated the eligibility criteria for students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, and furthered mandates forbidding discrimination against students. By 1972, 25 million students across the nation were enrolled in the program.

Privatizing the Lunchroom

Changes during the 1960s and 1970s resulted in a greatly expanded, more expensive school lunch program. High unemployment coupled with high inflation, dubbed “stagflation,” frustrated the nation throughout the late 1970s and caused the rolls of schoolchildren eligible for free and reduced-priced lunches to soar. Districts had to provide meals to more children, purchase increasingly expensive food, hire additional food-service personnel, and expand cafeteria facilities. As schools looked for ways to fund their growing programs in a deflated economy, they turned increasingly to private partners.

Simultaneously, the federal government reduced its subsidy for full-price lunches, and state allocations failed to cover the costs of increased participation, which reached 2.2 million students in Georgia by the 1982-83 school year. That year, for the first time ever, the number of children receiving free and reduced-price lunches exceeded the number purchasing full-priced lunches. This forced most school districts to raise the price of meals for the declining number of paying students. As the price of meals increased during the early 1980s, school lunch programs saw a 35 percent decline in student participation.

In an attempt to lure back paying student consumers and bolster their bottom lines, schools lowered the nutritive quality of meal offerings. Instead of soups, salads, and other vegetable-based dishes, cafeterias around the country began serving hamburgers, pizzas, tacos, and other fat- and sodium-laden meals. Fast food companies appeared in lunchrooms, and private food-service companies were hired to serve precooked, prepackaged foods that required less preparation.

Privatizing food service in public schools offered a way for districts to satisfy USDA requirements while also cutting costs. Although students had more choices, the focus on nutritional options declined. By the mid-1990s, the existence of vending machines in most school cafeterias marked a vast departure from the early attempts to provide children with nutritious meals.

School Lunch in the New Millennium

The goals of the National School Lunch Program have changed dramatically from those outlined in the original 1946 legislation, as have concerns over access to and participation in the program. Thanks to advances in food production, fortification, and distribution, once-common maladies like low bodyweight, rickets, and anemia are now rare. The daily diets and eating habits of U.S. schoolchildren have changed, and health experts once concerned by a lack of caloric intake now fret over rising obesity statistics.

During the 1970s and 1980s the federal government relaxed regulations on the amount of sugar, salt, and fat found in lunch offerings. As a result, the nutritional quality of meals declined significantly. Health professionals warned about childhood obesity as early as the late 1960s, and many today claim that the United States is facing an epidemic. Experts have pointed to the National School Lunch Program as both a major cause of the problem and a potential solution to at-risk populations.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, school lunch reformers pushed for the introduction of more fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products into cafeterias. Lawmakers and public health advocates began working to strike a greater balance between nutrition and taste, attempting to reverse the so-called “fastfoodification” of school cafeterias. The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA), championed by U.S. first lady Michelle Obama in 2010, represents the latest chapter in the story. The law introduced revised nutritional guidelines, regulated the sale of soft drinks and vending machine snacks, and granted access to the lunch program for thousands more students. By early 2015 more than seventy school districts in Georgia were enrolled in a new USDA program under the HHFKA that eliminates the paperwork for students applying for free or reduced-price lunches.

In the meantime, some districts, including the Atlanta Public Schools (APS), have taken drastic steps in the fight for a healthier school lunch. In August 2013 APS ceased offering fried foods during lunchtime in an effort to fight obesity and offer healthier meals to its more than 50,000 students. Individual schools across Georgia are also experimenting with school gardens and locally sourced foods, although such efforts have yet to make a substantive impact on the state or national scene.

Today the National School Lunch Program continues to spark debate over the nutritional value of foods served, the role of private industry, and the status of the program as a welfare initiative. A bigger and broader program more than sixty years after its original passage, the National School Lunch Program promises to remain a political hot-button.