During the late 1920s and 1930s the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) waged an ambitious campaign to encourage interracial cooperation and recruit new members in the Deep South. Party organizers experienced little formal success in Georgia but nonetheless aroused the ire of state and local officials who were committed to maintaining the state’s racial caste system and conservative labor traditions.

Background

In September 1919, in response to the Russian Revolution that began in 1917, a small but energetic number of American Communists formed two separate political parties, the Communist Party of America and the Communist Labor Party. The two organizations competed for members and legitimacy until 1921, when officials in Moscow, Russia, ordered their merger, forming the Workers Party, which later became the CPUSA.

After years of prolonged debate, delegates attending the Sixth World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1928 adopted a new policy to address the “Negro question,” pertaining to the ambiguous social and economic position occupied by African Americans in the American South and the United States more generally. African Americans belonged to a separate and oppressed nation, they concluded, subject to both systematic discrimination and economic injustice. As such, Black men and women were entitled to self-determination in areas where they predominated, particularly the Black Belt region of the Deep South. Moreover, the resolution directed the CPUSA to make African American recruitment the centerpiece of future organizational efforts.

For the CPUSA, whose membership was largely composed of white immigrants living in the industrial North, the Comintern’s orders posed a number of problems. Party leaders generally regarded the South as a mysterious, if not backward, region and openly questioned whether Black southerners possessed the revolutionary potential accorded them by Moscow officials. Their reservations notwithstanding, party leaders launched an ambitious campaign to combat racial discrimination and encourage interracial cooperation in the Jim Crow South. Party activists fanned out across the region to encourage radical protest and organize unemployed councils and revolutionary unions, and by 1930 the CPUSA had established a weekly newspaper, the Southern Worker, which was published in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and circulated throughout the region to encourage communication among the party faithful.

Despite the sometimes heroic efforts of Communist organizers, the southern campaign yielded few new names to the party’s membership rolls. Though they, too, suffered economic hardship, white workers were seldom willing to forsake their racial privilege for illusory promises of reform. Likewise, Black workers understood too well the risks posed by making common cause with northern revolutionaries. Religious fundamentalism and perceived cultural insensitivities also stymied the party’s advance, as did the willingness of white officeholders to employ southern judiciaries as tools of state suppression. Apart from Alabama, where the party enjoyed strong support in Birmingham’s steel industry and where thousands of sharecroppers and tenant farmers joined the CPUSA-sponsored Sharecroppers Union, Communist organizers failed to establish a sustained, formal presence anywhere in the South.

Still, its shortcomings notwithstanding, the CPUSA enjoyed a notoriety in the region that belied its small numbers. The party’s legal affiliate, the International Labor Defense (ILD), won widespread support from African Americans and white liberals for its defense of indigent Blacks in high-profile court cases, and even briefly competed with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as the nation’s foremost protector of African American civil rights. Communist organizers led large-scale strikes and demonstrations in the region as well, earning admiration for the party in some quarters but condemnation in others. In the late 1920s and 1930s then, the Communist Party attracted numerous sympathizers and critics in the region, but few new members.

Georgia’s Radical Labor Movement

The high-water mark of Communist activity in Georgia occurred in the early 1930s, when the state’s economy was suffering from the ravages of the Great Depression. According to CPUSA records, by 1932 only a small number of party members were active in Atlanta, and the statewide apparatus was in disarray. But despite their small number, Georgia’s Communists attracted a good deal of attention from state and local officials, in part because party activists were believed to have precipitated a violent strike in Gastonia, North Carolina, in 1929.

Party members experienced their first brush with Atlanta lawmen in the spring of 1930, when police arrested six suspected Communists in two separate raids on Communist-sponsored labor meetings. For the alleged crime of holding a private meeting to discuss labor activism, authorities charged the suspects with “attempting to incite insurrection” under an antiquated insurrection statute that dated from the antebellum period and carried a possible death sentence. Originally passed to discourage slave rebellions, the law was revised in the late 1860s to address insurrection but largely forgotten thereafter. Despite years of neglect, the statute became prosecutors’ preferred tool for pursuing radicals in the years that followed.

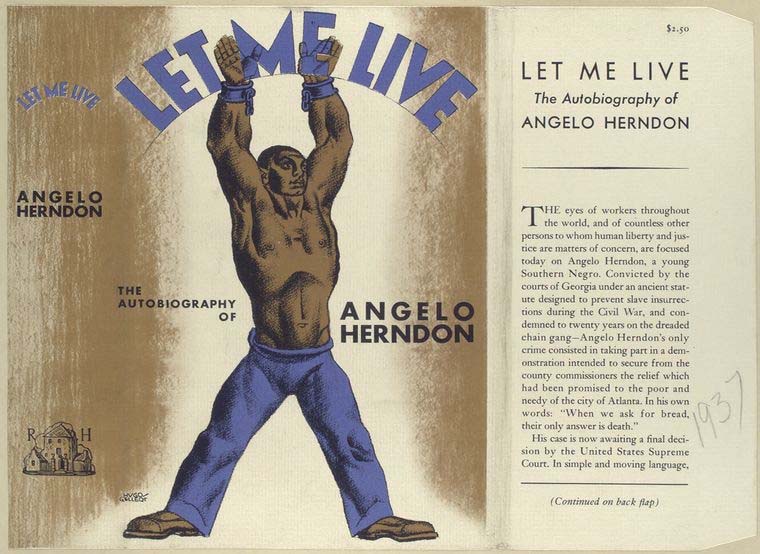

For their defense, the “Atlanta Six” turned to the ILD, which functioned as the legal arm of the Communist Party. ILD attorneys employed a variety of legal maneuvers to postpone their clients’ trial until 1932, when authorities tabled their charges to accommodate the prosecution of Angelo Herndon, a Communist organizer deemed more dangerous by Atlanta officials.

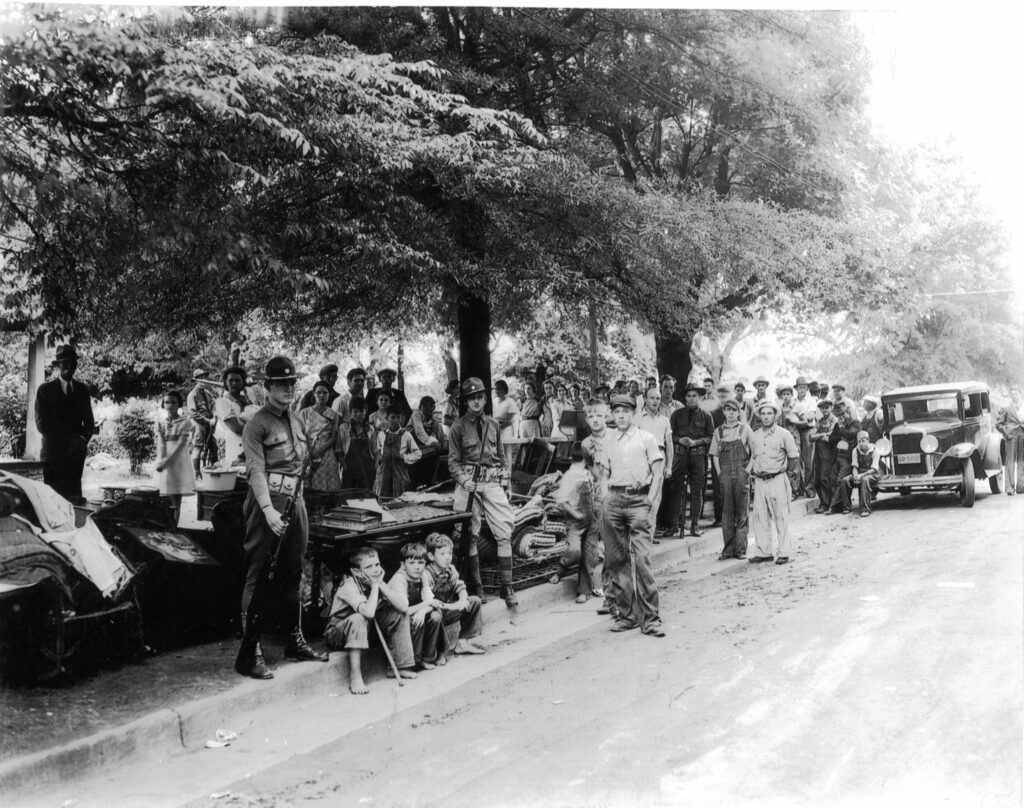

Economic conditions in the city continued to worsen, and by the summer of 1932, Atlanta’s fragile safety net had begun to fray. Tensions reached a boiling point on June 30, 1932, when more than 1,000 out-of-work laborers marched on the Fulton County Courthouse, demanding the resumption of relief payments that were suspended only days earlier. The provision of emergency relief payments appeared to satisfy the workers’ demands, but officials remained shaken by the depth of labor unrest. For Atlanta officials, the demonstrators’ mixed racial composition was perhaps more alarming than their number. It led authorities to suspect the influence of Communist organizers, and they began plotting a citywide dragnet to suppress radicalism and protect the region’s racial customs.

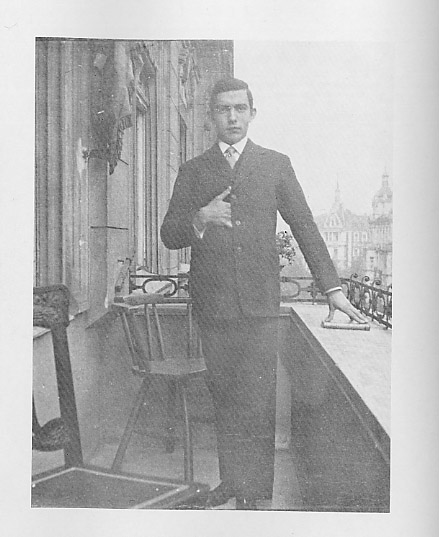

After less than two weeks of surveillance, police arrested Herndon, an African American and avowed Communist who, like the Atlanta Six, was subsequently charged with “attempting to incite insurrection.” Though it initially attracted little interest, Herndon’s arrest was but the first step in a five-year legal odyssey that focused national attention on Georgia’s controversial insurrection statute and raised prescient questions about the legitimacy of “southern justice.”

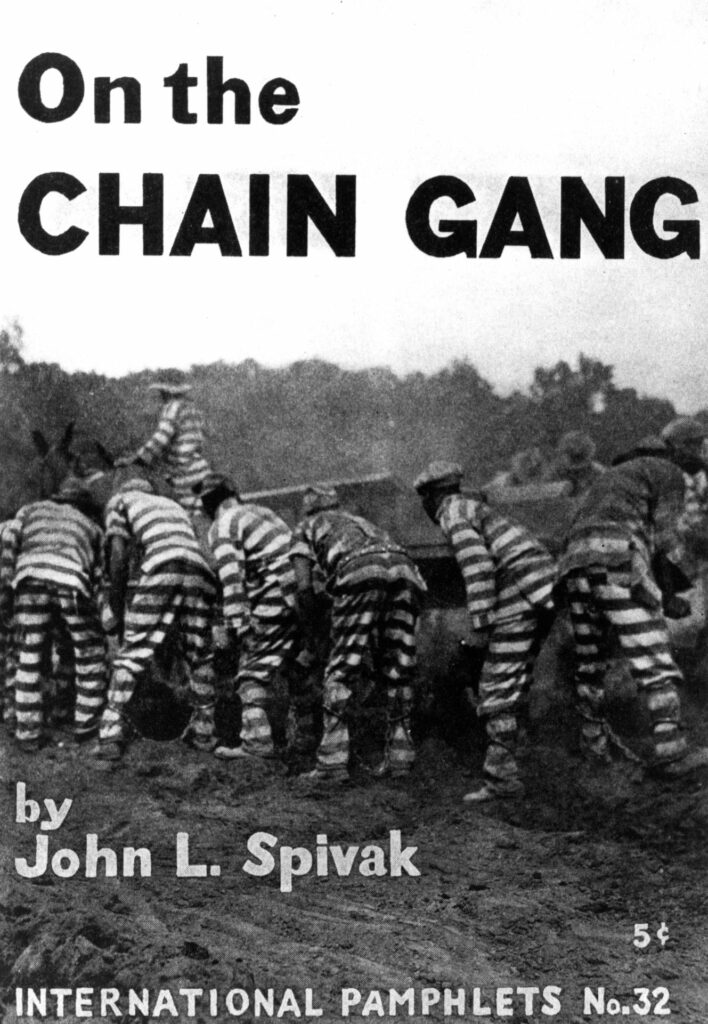

Authorities redoubled their efforts while Herndon’s case progressed through the courts, conducting “Red Raids” on locations of interest with only a casual regard for civil liberties. The CPUSA meanwhile kept a watchful eye on Georgia’s penal system; in 1932 the party’s newspaper, the Daily Worker, published John Spivak’s novel Georgia Nigger in serialized form. Well received at the time of its publication, the book helped to expose the deplorable conditions that prevailed in Georgia’s notorious chain gangs and ultimately contributed to a groundswell of support for their reform.

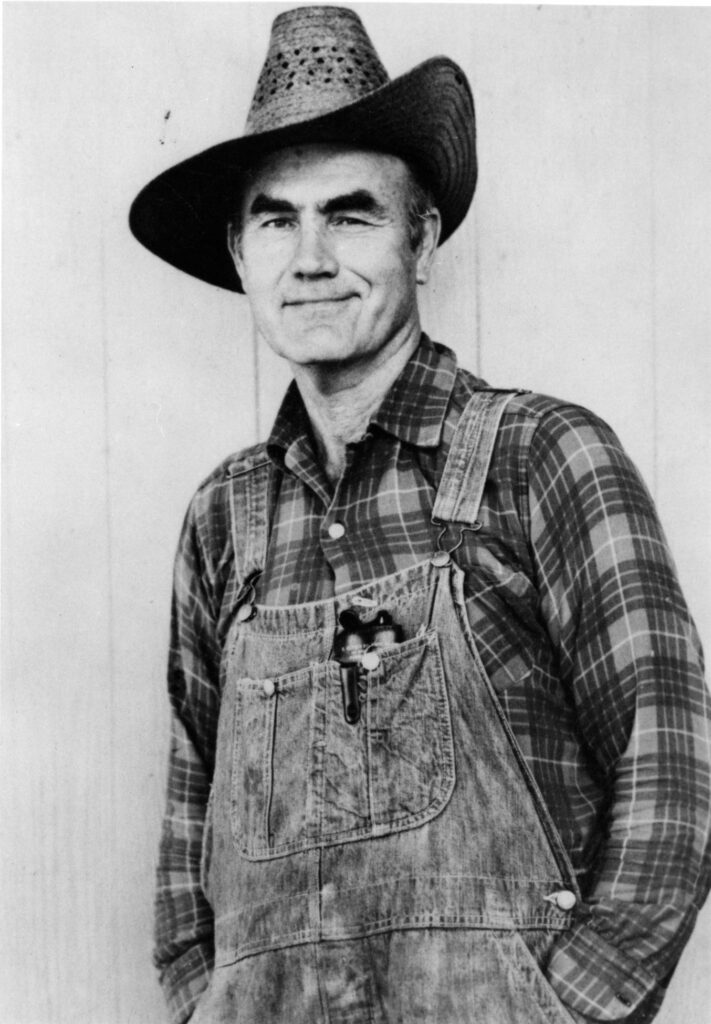

In the spring of 1934 the Supreme Court of Georgia issued its decision upholding Herndon’s conviction, prompting another series of raids on suspected Communists. Under the direction of Assistant Solicitor General John H. Hudson and Solicitor General John A. Boykin, the principal architects of Atlanta’s antiradical defenses, authorities launched multiple raids but failed to apprehend the Georgia-born poet and activist Don West, who had emerged as Boykin and Hudson’s principal target. As the head of a committee charged with soliciting local support for Herndon’s defense, West aroused the interest of authorities and narrowly escaped arrest before collaborators arranged for his departure from Atlanta. When raids conducted elsewhere in the city uncovered caches of party literature, Hudson reported the seizure of documents implicating thousands of local Communists, though the actual number was much closer to ten.

Fears of Communist activity only increased the following September, when some 44,000 laborers statewide participated in the textile worker strike of 1934. Skirmishes between lawmen and laborers ensued in communities throughout the state, and Governor Eugene Talmadge declared martial law in areas deemed most volatile by officials. When National Guardsmen restored order after two weeks of hostilities, state authorities announced their belief that Communists and outside agitators had provoked the strikes, and they launched yet another series of raids to apprehend the guilty parties. State newspapers applauded the arrests of fifteen “radicals” in Shannon, in Floyd County, and twelve suspected Communists in Atlanta and Decatur, and urged officials to act with a heavy hand. “There is only one way to deal with communism,” averred the Atlanta Constitution, “and that is to crush its ugly head whenever it shows above the surface. It is the enemy of good government, serves no good purpose, and prospers only through the creation of discontent and the violation of law and order.”

While Georgia’s anticommunism campaign still enjoyed wide public support, a handful of prominent liberals expressed concern over the suspension of civil liberties in the wake of the state’s textile strikes. In October 1934 representatives of the Urban League, members of both the Black and white clergy, and Emory University president Harvey W. Cox publicly urged state officials to exercise greater caution when pursuing radicals in the months ahead. Unmoved by liberal opinion, Boykin meanwhile proposed a model sedition bill to complement the state’s insurrection statute. State legislators approved Boykin’s bill and a second act barring the Communist Party from state ballots, but Governor Talmadge vetoed both measures when they reached his desk in the spring of 1935.

Liberal objections notwithstanding, Atlanta’s anti-Communist campaigns continued until the spring of 1937, when the U.S. Supreme Court rendered its decision in the Angelo Herndon case. By a five-to-four margin the court dismissed Herndon’s conviction and declared unconstitutional the state’s application of the insurrection statute. Writing for the majority, Justice Owen J. Roberts determined that “as construed and applied,” the controversial law functioned as “a dragnet which may enmesh anyone who agitates for a change of government if a jury can be persuaded that he ought to have foreseen his words would have some effect in the future conduct of others.”

Despite the court’s judgment, anticommunism still enjoyed wide public support and Georgia remained a hostile environment for party organizers. Boykin moreover refused to drop charges against the seventeen other suspects indicted under the state’s insurrection statute. To avoid prolonged and costly court battles, the financially distressed ILD made regular bond payments on behalf of the accused until 1939, when charges were finally dropped.

The “Red Scare” of the 1950s

During the late 1940s and early 1950s anti-Communist hysteria, much of it fueled by hearings held by the Congressional House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), gripped the nation. In 1950 Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy joined the fray and captured headlines by alleging that Communists and subversives had infiltrated the U.S. State Department, armed forces, and other prominent American institutions. To identify suspected Communists, McCarthy organized a series of hearings between 1950 and 1954, soliciting testimony from hundreds of individuals, including Georgia author Grace Lumpkin. Though she had been involved with the party (but not a member) during the 1920s and 1930s, Lumpkin embraced reactionary politics later in life and willfully divulged the names of radical acquaintances when she appeared before McCarthy’s Senate subcommittee in 1953.

McCarthy’s influence diminished tremendously following his censure in 1954, but anticommunism remained a powerful force in American politics. At the state level officials employed Georgia’s “Education Commission” to investigate and intimidate suspected Communists involved in the civil rights movement, including Martin Luther King Jr. At the federal level congressional subcommittees organized a total of eight hearings on radicalism in southern cities between 1954 and 1958, though many observers later concluded that legislators were more interested in discrediting integrationists than foiling a verifiable Communist threat.

Classical music composer and Albany native Wallingford Riegger was summoned to appear before HUAC in 1957, but he refused to answer the committee’s questions, citing his First Amendment rights.

In 1958 HUAC investigated communism in Atlanta but failed to produce evidence of substantial Communist activity. Georgia labor activist Don West, who had appeared before a similar hearing in Memphis, Tennessee, the previous year, was subpoenaed but not called to testify. John Hester, who had previously worked alongside West selling fruits and vegetables, was the only Georgian, albeit a former one, to testify before the committee.

Conservative interests in Georgia and elsewhere meanwhile exploited the public’s fear of communism to stymie liberal reform. In the 1950s Dalton mill owners alleged Communist influence when union representatives attempted to organize workers in the state’s carpet industry, and Black activists were particularly vulnerable to charges of communism during the civil rights era. Film producers blacklisted the Georgia-raised entertainer Lena Horne for her political activism following HUAC’s investigation of Communist influence in Hollywood during the 1950s. The Federal Bureau of Investigation squandered considerable resources in their failed campaign to substantiate claims linking King to Communist interests.

Legacy

Assessing the success of Communist efforts in Georgia remains a difficult task. By exposing the shortcomings of the state’s judicial and penal systems, Communist activists helped contribute to the reform of those institutions. Though it recruited few new members, the CPUSA at times enjoyed significant support from Black southerners. Moreover, party activists worked productively with other liberal organizations on occasion, but their ideological rigidity more often alienated potential supporters. As a result, anticommunism, rather than reform, may ironically have been the greatest legacy of Communist organizing.