Between 1961 and 1965 the state of Georgia took part in the commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Civil War (1861-65).

Following the lead of the federal government, which had established the Civil War Centennial Commission in 1957, Georgia created in 1959 a state commission, which subsequently encouraged local communities to carry out commemorative events in their areas. The commission’s goals included using the anniversary as a means for education and reflection on the war and its legacy, as an opportunity for the collection and preservation of materials and documents related to the war, and as a vehicle for encouraging cultural tourism and economic development throughout the state.

A variety of events and programs occurred during the centennial, and several books, television documentaries, historical markers, and museums appeared as products of the commemoration. However, because the official centennial activities in Georgia took place entirely on the white side of the color line, the effort to encourage the public to reflect on the war’s legacy of slavery and emancipation remained incomplete.

The anniversary coincided with the height of the civil rights movement in Georgia and the South. Some white Georgians used the commemoration to glorify the Confederacy, adopting its leaders, rhetoric, and symbols as a means for expressing resistance to civil rights ideals. While not all centennial efforts were driven by that agenda, the official commemorations upheld an idealized vision of antebellum plantation culture, celebrated Confederate military heroes, and omitted references to slavery as a cause for the war, all of which are characteristic of Lost Cause ideology.

Georgia Civil War Centennial Commission

Governor Ernest Vandiver Jr. issued an executive order creating the Georgia Civil War Centennial Commission on April 10, 1959. He named his executive secretary, Peter Zack Geer, as chairman and appointed seventeen commission members, all of whom were white. The commission members organized themselves into nine committees (arts participation, central research, education, finance, monuments/memorials/commemorations, official souvenirs, pageants and reenactments, publications, and publicity and promotions) and brought additional white men and women into their work.

With loaned staff assistance from the state chamber of commerce, and with $25,000 in funding, the commission set up an office in Atlanta and began to publicize its plans. An early goal of the commission was obtaining cooperation from educational and cultural groups across the state. State budget restrictions and a downsizing of state government staffing impeded the progress of the commission in its first months. Stanley Rowland Smith, a public relations professional, became the administrative director in October 1960, and he served for the remainder of the commemoration.

The Georgia Civil War Centennial Commission, from the beginning, encouraged counties to form groups that would carry out activities at the local level, and it published a pamphlet, Civil War Centennial Manual for Georgians: A Guide to Local Committees, to help them do so.

Centennial’s First Year: 1961

Several patriotic organizations in Savannah organized the first commemorative activity of the centennial, which took place on January 3, 1961, to mark Georgia’s seizure of Fort Pulaski from the United States 100 years earlier. A troop representing the Oglethorpe Light Infantry lowered the American flag and raised the Georgia flag. Governor Vandiver sent telegrams, using the words of Governor Joseph E. Brown, to the governors of other southern states informing them of the transfer.

Rich’s Department Store in Atlanta mounted a tableau of Civil War military leaders and an exhibition of weapons and artifacts in its downtown store. The Atlanta Constitution noted that the exhibition was “enough to turn Lee’s head” because a statue of him was situated in the midst of the women’s lingerie department.

From January 19 to 21 Milledgeville commemorated Georgia’s secession with a parade, a tour of homes, and a reenactment of the secession convention at the old state capitol building. The inauguration of U.S. president John F. Kennedy in Washington, D.C., kept Governor Vandiver and commission chairman Geer from attending the Milledgeville events.

In March 1961 Atlanta sponsored a “re-premiere” of the movie Gone With the Wind (1939) , as well as an antebellum-attire costume ball. Two of the film’s stars, Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland, along with producer David O. Selznick, attended the screening, which was held at Loew’s Grand Theater, the site of the original premiere. The Atlanta events were envisioned as fund-raisers for the commission and its programming. However, despite the large crowd in attendance, the events did not produce the kind of profits that had been predicted.

The commission sponsored the production of a television and radio series entitled Understanding the Civil War. Ten thirty-minute presentations were recorded and aired on television stations across Georgia during 1961. Allen Phelps “Ned” Julian, the director of the Atlanta Historical Society and a former army colonel, served as the scholar and researcher for the programs.

Centennial’s Second Year: 1962

In April 1962 local historians in northwest Georgia staged a reenactment of the Andrews Raid from Kennesaw to Chattanooga, Tennessee. The L & N Railroad allowed the reconditioned locomotive the “General” to be activated for the event. Two passenger-train cars full of spectators followed the locomotive, and other costumed spectators turned out to meet the trains as they passed through communities along the route. An estimated 200,000 people were present from one end of the line to the other. Walt Disney’s film The Great Locomotive Chase (1956) was used as a background source for the reenactment.

Centennial’s Third Year: 1963

In January 1963 Carl Sanders became governor, and Geer became lieutenant governor. Governor Sanders issued his own executive order, which appointed insurance executive Beverly Dubose Jr. of Atlanta as the new commission chairman. Dubose, one of the more active members of the original commission, came to the chairmanship full of ideas for a heavy slate of commemorative programming. What he did not have were the funds to implement them all.

During the summer and fall of 1963, Chickamauga National Battlefield Park held a series of “state days,” which commemorated the participants from both Northern and Southern states who fought at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863. Descendants of these soldiers were invited, along with other cultural travelers, to visit the battlefield monuments erected at the park. The final state day was Georgia Day, which featured a parade and a speech by the local congressman.

Centennial’s Fourth Year: 1964

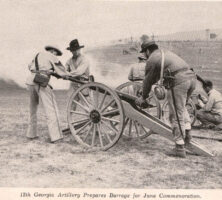

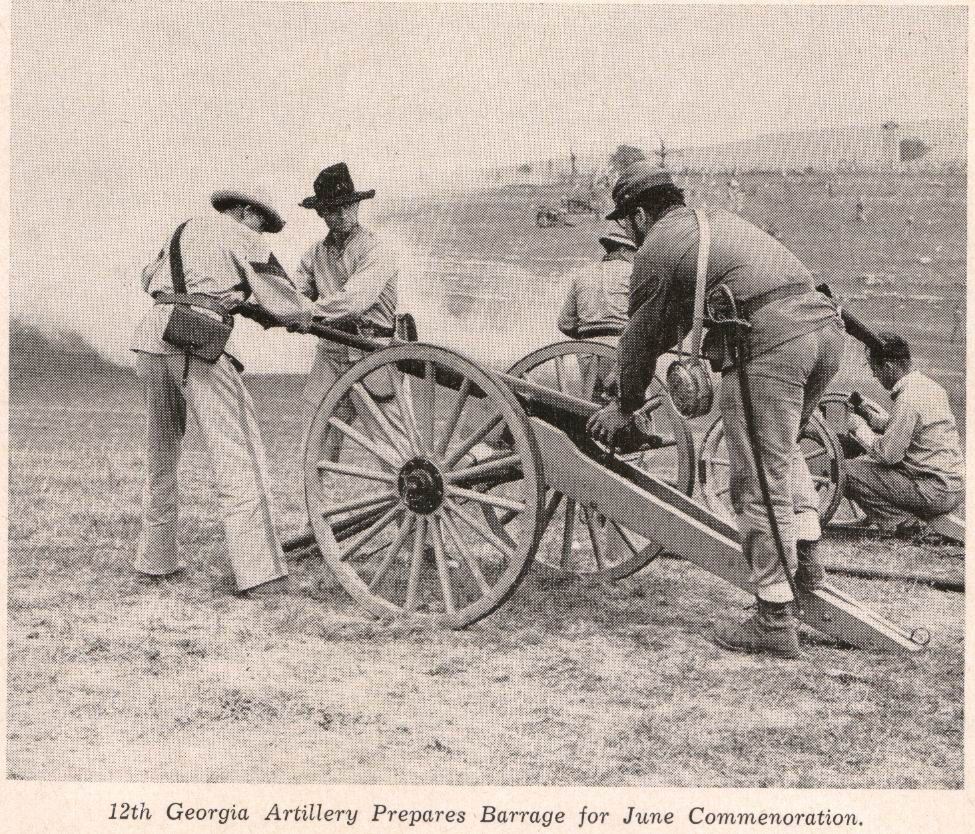

Given the level of military activity in Georgia in 1864, including Union general William T. Sherman’s Atlanta campaign and march to the sea, the commission designated 1964 as “Georgia’s Year.” The commission developed a yearlong radio program series, Georgia Civil War Centennial News, which offered daily two-minute clips recounting events that occurred on those dates. Battle reenactments took place along the route of the Atlanta campaign, including events at Resaca, New Hope Church, Kennesaw Mountain, Atlanta, and Jonesboro. The Resaca, New Hope Church, and Jonesboro reenactments took place on portions of the original battlefield that were privately owned.

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain reenactment took place on June 27, the actual centennial date of the battle, but was held at a farm owned by Cobb County, rather than on the actual battlefield. The National Park Service, which owned the original battlefield, had a policy that prohibited reenactments on its sites. The Kennesaw reenactment came at the end of a week of festivities, including a parade, memorial service, barbecue, costume ball, and tours. Despite intentions to make the reenactment as accurate as possible, it appeared to spectators, once the skirmish started, that the ratio of Confederate to Union troops was not accurate and that the Confederates were winning the battle (which history suggests should end in a draw). Approximately 7,000 people watched the mock battle, which featured 2,000 participants.

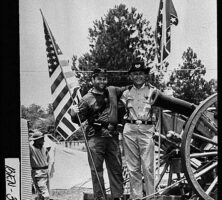

Development in the Atlanta area created difficulties in locating a site where the Battle of Atlanta could be reenacted. Ultimately, the event, which featured reenactments of maneuvers from multiple battles, took place at Stone Mountain, on the field in front of the carving of Confederate leaders Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. Four hundred people participated in the reenactment, and approximately three thousand spectators observed.

Another major event of 1964 was Atlanta’s hosting of the Seventh Assembly of the National Civil War Centennial Commission and state commissions from across the United States. Historian James “Bud” Robertson, a graduate of Emory University in Atlanta, was the executive director of the national commission. After Dubose assured Robertson of the availability of integrated public accommodations in Atlanta, the event went forward and included a lecture by journalist Ralph McGill, tours of the Cyclorama and Stone Mountain, a band concert, a boat ride, and a wreath-laying.

Centennial’s Final Year: 1965

Working with an Atlanta television station, the commission produced a thirty-minute film entitled Death Knell, which chronicles the fall of Atlanta and the effects of that battle’s outcome on U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s reelection and on the final months of the war. The film was distributed to schools and was also used by Civil War Round Tables, a national historical society that organized programs in various cities. (The Atlanta Civil War Round Table, founded in 1949, is still active today.)

Working with the city of Atlanta, the commission mounted Georgia Historical Commission markers about the Battle of Peachtree Creek, the Battle of Ezra Church, and the Battle of Atlanta. Maps, wayside signage, and landscaped parking areas complemented the markers, creating small parks.

The commission also cooperated with the town of Fitzgerald to stage the drama Our Friends, the Enemy and to build the Blue and Gray Museum. Fitzgerald was established in the 1890s as a “colony” founded and settled by Union veterans from Indiana and other locations in the North. Fitzgerald had lobbied the national commission to be the site of the closing event of the national commemoration, which did not come to pass; however, the Georgia commission scheduled its own disbanding to occur soon after Fitzgerald’s “Blue and Gray Days” (a reunion for Union and Confederate veterans and their descendants) in 1965.

Other Legacy Projects

Around the period of the centennial, many other legacy projects not sponsored by the commission took place around the state. A visitors’ center was built at Fort McAllister, a Confederate earthworks in Bryan County. In Columbus, underwater archaeologists worked to retrieve the remains of the ironclad CSS Chattahoochee , which later became the core of the collection at the Confederate Naval Museum (later the National Civil War Naval Museum at Port Columbus). Other historical markers were mounted, and collections of photographs, papers, and artifacts found their way into archives and museums to be preserved and shared with the broader public.