The blues is a blending of African and European traditional music characterized by its melancholy (or blue) notes expressing suffering and deprivation. Songs are typically structured in three-line verses, with the third line summing up, or rephrasing, the sentiment expressed in the first two.

Beginning in the nineteenth century, blues music developed throughout the southern United States from the work songs and field hollers of enslaved people. Later, southern prisoners in jail and on chain gangs added songs of murder, death row, and their treatment at the hands of the wardens. In 1839 one of the earliest known references to slave music that would evolve into the blues was documented on a Georgia rice plantation by an English traveler.

Early Performers

Georgia has produced a rich blues heritage that showcases a variety of performance styles, from such popular commercial recording artists as Ray Charles from Albany, Little Richard from Macon, and Robert Cray of Columbus to more obscure players like Blind Simmie Dooley from Hartwell and Dolphus “Gus” Gibson from Fort Valley.

Little is known about the earliest forms of the music, but Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, a native of Columbus, claims to have sung blues in front of live vaudeville audiences at the age of sixteen (around 1900), which may make her the first professional female blues performer. Before relocating to Chicago, Rainey performed at the 81 Theater in Atlanta, where she influenced the teenaged Bessie Smith. Also in the early years of the century, Atlanta’s Decatur Street had a thriving music scene populated by barrelhouse blues pianists like Thomas Andrew “Georgia Tom” Dorsey from Villa Rica, Big Maceo Merriweather from Atlanta, and Willie Lee “Piano Red” Perryman from Hampton. (The term barrelhouse was used to describe a loud percussive type of blues piano suitable for noisy bars or taverns.)

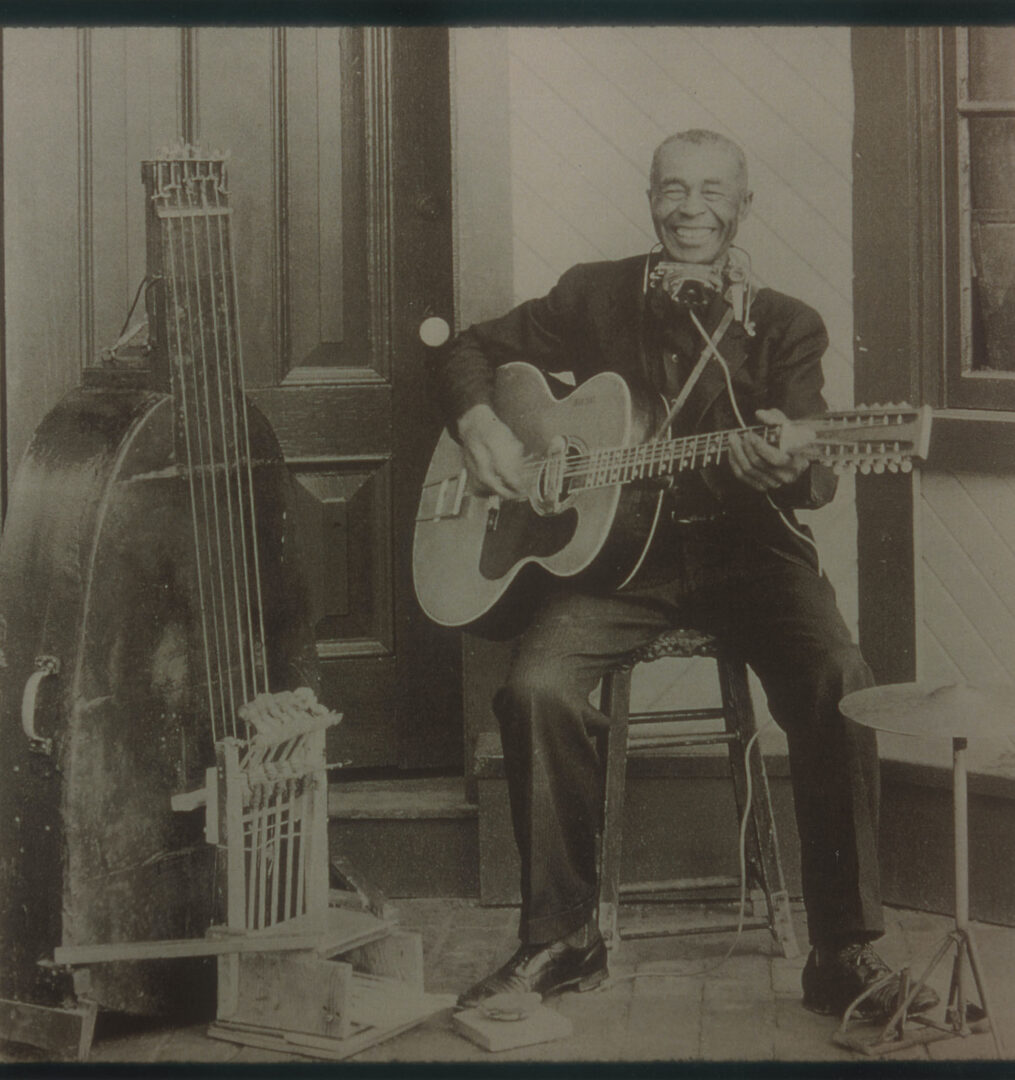

From the mid-1920s into the early 1930s, “artist and repertoire” (known as A&R) staff scoured the South and northern cities in search of talent for the race-record subsidiaries of major record companies. During Jim Crow, so-called race records denoted recordings of Black artists that were marketed primarily to Black audiences (the category was later renamed rhythm and blues). In Atlanta they recorded a distinct style of country blues performers. The use of twelve-string guitars, more strumming than picking, irregular rhythms, and a nasal vocal technique typified the Atlanta sound, as performed by brothers Robert “Barbecue Bob” Hicks from Walnut Grove and Charlie “Lincoln” Hicks from Lithonia.

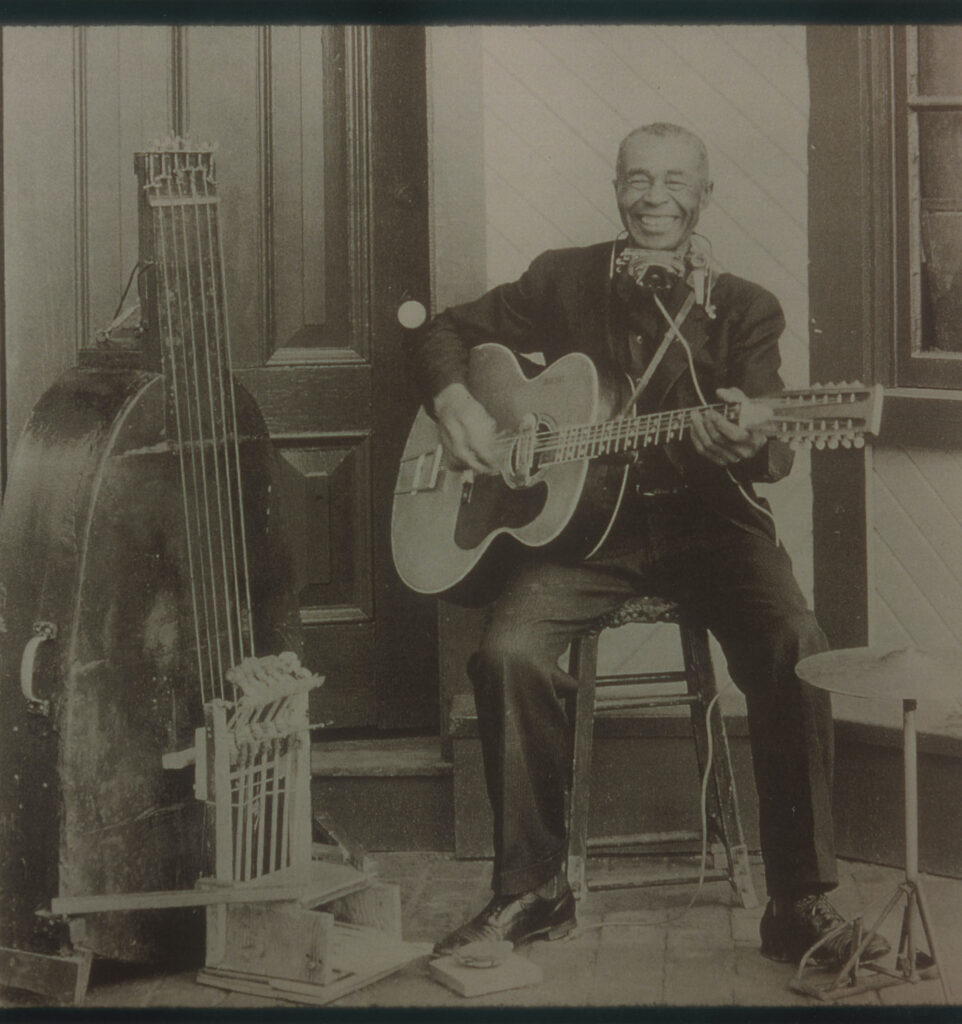

The influence of the intricately finger-picked Piedmont style of country blues also appeared in Georgia with Eugene “Buddy” Moss from Jewell and Joshua Barnes “Peg Leg” Howell from Eatonton, who maintained one of the most successful early blues recording careers into the 1930s. “Blind Willie” McTell from Thomson, another country blues singer active from the 1920s, played in Atlanta until shortly before his death sometime in the late 1950s, and like many “songsters” of the day, he incorporated a wide variety of popular song styles in his repertoire. A longtime resident of the city, McTell often played on the street outside of the Pig 'n’ Whistle barbecue stands and collaborated with the Hicks brothers, Buddy Moss, Curley Weaver from Covington, and Piano Red.

Chicago Blues

In Chicago, African Americans who had migrated from the South during the Great Migration formed a new style of urban blues, and by 1928 two of the most famous and widely recorded blues performers in America were Georgia Tom and “Tampa Red” Whittaker from Smithville. Even though the number of blues recordings began to wane after the Great Depression and into the 1940s, the genre remained a popular form of expression in northern cities. Georgia-born guitarists James “Kokomo” Arnold from Lovejoy, J. B. Hutto from Augusta, Joe Carter from Midland, and Big Maceo Merriweather contributed to the urban blues scene in Chicago through the middle of the century.

Blues Revival

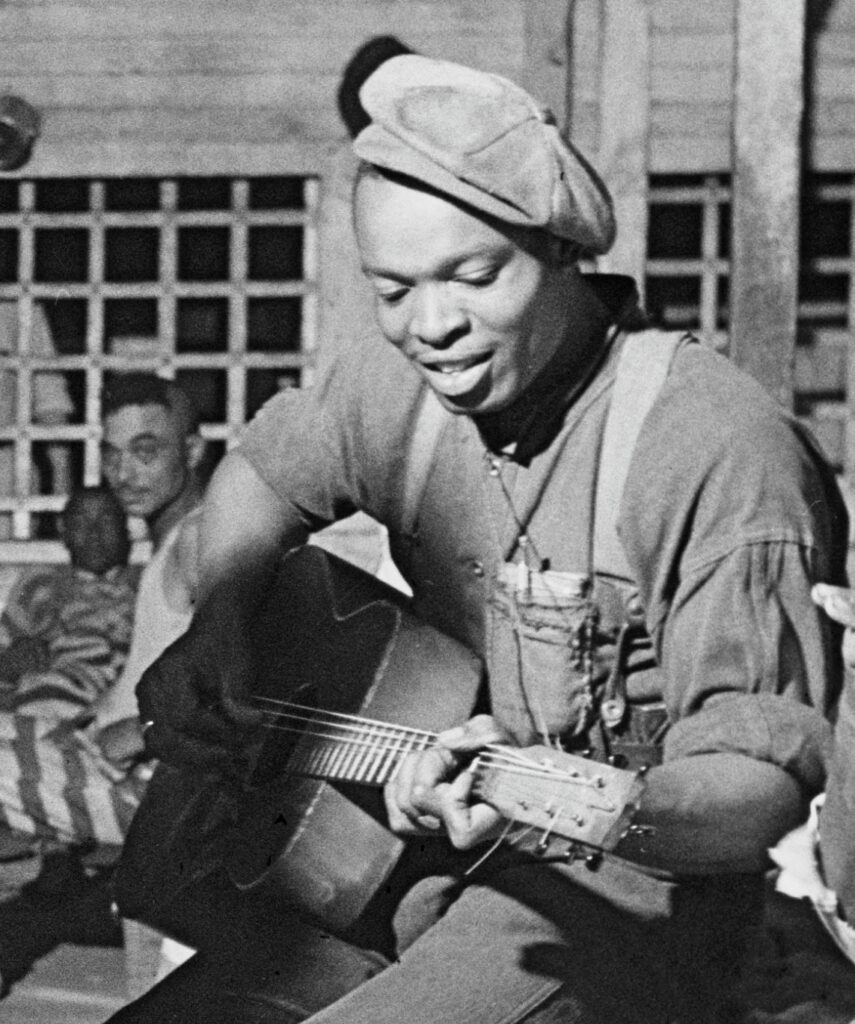

When white listeners became interested in blues music in the late 1950s and early 1960s, many of the country blues musicians had ceased playing music or lived in obscurity until blues revivalists searched them out. Jesse Fuller from Jonesboro, a one-man band, and harmonica player Buster Brown from Cordele benefited from the renewed interest in their music, but the blues revival treated no early Georgia blues musician better than Sonny Terry (Saunders Terrell) of Greensboro. From his first recording in 1937, Sonny Terry remained active in music and even played Carnegie Hall and on Broadway, but his popularity grew in the 1960s. Solo and with his longtime partner, guitarist Brownie McGhee, Terry played numerous festivals and recorded many albums until the 1980s.

By the time the blues began to have an overt influence on white musicians like the Allman Brothers of Macon in the late 1960s and early 1970s, white performers had overtaken their Black peers in popularity, and increasing numbers of white musicians, like Tinsley Ellis of Atlanta, began playing the blues. Luther Johnson of Davisboro, who played extensively with Muddy Waters, and other important blues musicians of the 1970s were often overshadowed by white contemporaries, a trend that continues to this day. Georgia still produces blues by performers like Neal Pattman from Madison County and Robert “Chick” Willis of Cabiness, but blues tourism and the record industry continues to homogenize the genre, and the distinctive traditions of the early blues records and the Atlanta style no longer remain.