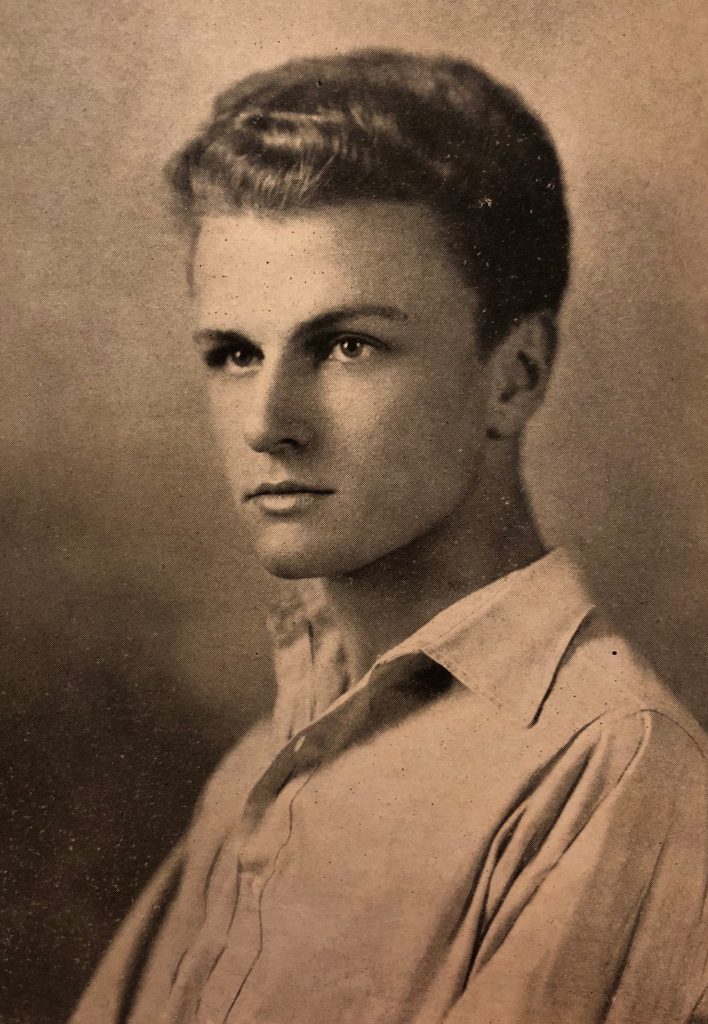

Ernest Hartsock was an award-winning poet, editor, and publisher. Though largely forgotten, Hartsock and his press, Bozart, existed at the center of Atlanta’s poetry scene during the 1920s.

Ernest Abner Hartsock Jr. was born in Atlanta on May 5, 1903, to Ernest Abner Hartsock Sr. and Alta May Sanner, both originally from Maryland. After attending Boys High School, where he wrote for the school newspaper, Hartsock earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Emory University in 1925 and 1926, respectively. As an undergraduate, Hartsock worked for the Latin department and then taught English classes while earning his master’s. In 1925 Hartsock published his first collection of poetry, Romance and Stardust. He also served as an editor of the Emory Phoenix, the university’s literary magazine, and was published in national poetry journals.

After earning his master’s degree, Hartsock was hired to teach English at the Georgia School of Technology (later Georgia Institute of Technology). While at Georgia Tech, Hartsock founded the Bozart Press, eventual publisher of the “little magazine” Bozart: The Bi-Monthly Poetry Review and fifteen books of poetry. The press’s distinctive name was adopted as a rejoinder to H. L. Mencken, who famously ridiculed the South and its cultural milieu, calling it “the Sahara of the Bozart.” Bozart would become the second-largest poetry publication in the country, claiming among its subscribers the upper echelon of the poetry world. In 1927 Hartsock published his second book of poetry, Narcissus and Iscariot.

Thornwell Jacobs, president of Atlanta’s Oglethorpe University, named Hartsock the inaugural professor of poetics in 1929, a position Hartsock would hold until his death. Also in 1929, the Poetry Society of America awarded Hartsock its top annual prize for his poem “Strange Splendor.” Hartsock, unable to afford the trip to the New York City ceremony, was sponsored by the Atlanta Journal, for which he often wrote book reviews.

Based on the success of his publication and notoriety gained by his published poems, Hartsock was in high demand as a lecturer and guest columnist. He traveled widely across the Southeast to visit poetry societies and universities offering readings and presentations. Struggling financially his whole life—he supported his mother and father—Hartsock lectured and taught until he was ordered to bed by his doctors. Hartsock’s health worsened dramatically in the fall of 1930, and on December 14 he succumbed to pernicious anemia at Wesley Memorial Hospital (later Emory University Hospital) in Atlanta. His final book of poetry, Strange Splendor, had been published two months before his death. The historian C. Vann Woodward, one of his closest friends from Emory, was at his side when he died.

Today, few physical reminders remain of Hartsock. The Philip Weltner Library at Oglethorpe University displays a bronze bust by German-born sculptor and Oglethorpe art professor Fritz Zimmer as well as a plaster bust by fellow Atlanta poet and Hartsock friend Blossom Tucker. Hartsock’s papers are housed in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory.

Hartsock was buried at Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery. His father and mother were later buried there in 1938 and 1960, respectively. A large bronze plaque with his poem “Second Coming” stands in the Hartsock family plot. After their son’s death, Hartsock’s parents transferred ownership of the Bozart Press and journal to Oglethorpe. Jacobs and Benjamin Musser, a New Jersey–based poet and friend of Hartsock, would serve as coeditors.

Admirers published remembrances of Hartsock in national periodicals following his death, and friends and family mourned his passing at memorials in Atlanta. A plaque, now lost, was unveiled at Atlanta Public Library’s main branch. There was even a brief movement to purchase his final home and create a memorial and poetry museum near Emory University’s Decatur campus.