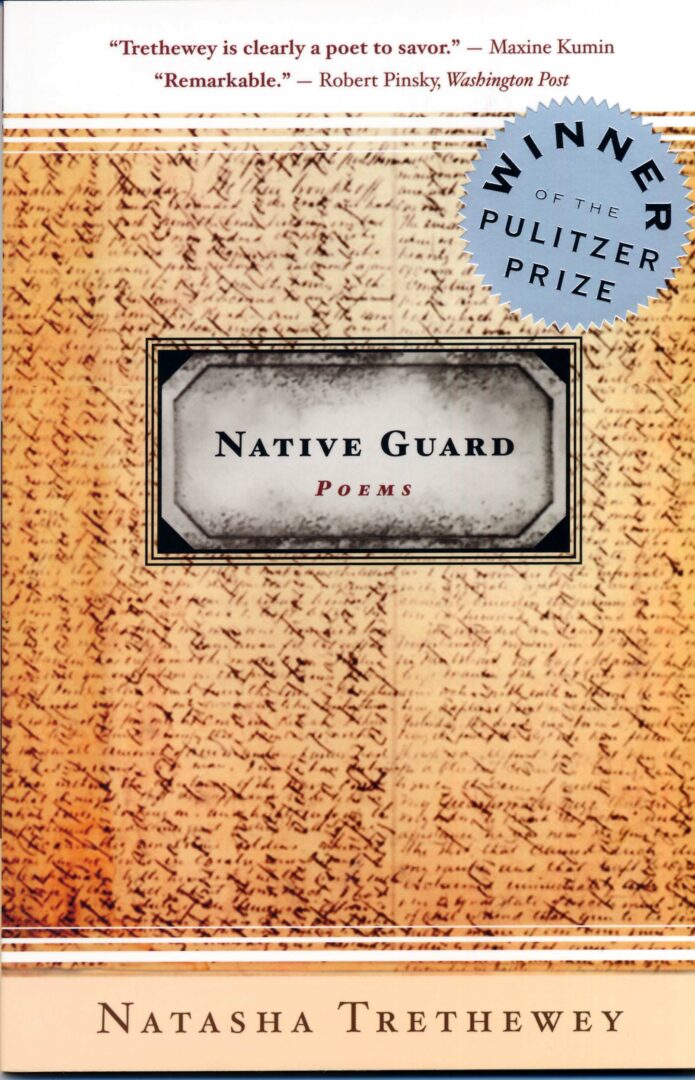

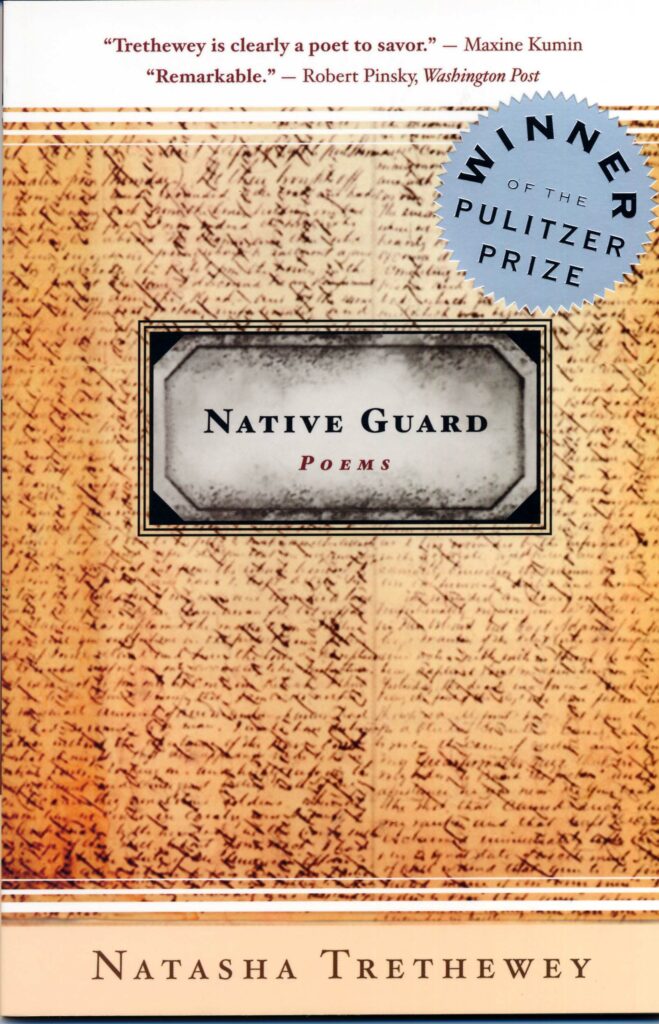

Natasha Trethewey served as poet laureate of the United States from 2012 to 2014. Her collection Native Guard won the Pulitzer Prize in poetry in 2007.

Trethewey’s works forge a rich intersection between the historical and autobiographical. In poems that are polished, controlled, and often based on traditional forms, Trethewey grapples with the dualities and oppositions that define her personal history: Black and white, native and outsider, rural and urban, the memorialized and the forgotten. The daughter of a Black mother and a white father, Trethewey grew up in a South still segregated by custom, if not by law, and her life astride the color line has inspired her recovery of lost histories, public and private.

Early Life and Career

Although Trethewey has spent much of her life in Georgia, she maintains deep roots in her native Mississippi, where she was born on April 26, 1966, in her mother’s hometown of Gulfport. Her parents, Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough, a social worker, and Eric Trethewey, a poet and Canadian emigrant, met as students at Kentucky State College (later Kentucky State University) in Frankfort and later crossed the state line into Ohio to marry—a situation whose ironies and implications the poet deftly explores in “Miscegenation.”

After her parents’ divorce, six-year-old Trethewey moved with her mother to Atlanta, returning every summer to the Gulf Coast, where she split time between the homes of her mother’s family and of her father, who was then living in New Orleans, Louisiana. Here she began to discover the complexities of her essential duality—when she was with her father she could pass for white and be treated more equally than when she was among her mother’s people. Trethewey also began to write during these years, at her father’s urging.

Trethewey’s young adulthood was ruptured by violence and tragedy. In 1984 her mother divorced her second husband, Joel Grimmette; a year later, Grimmette shot his ex-wife to death. Nineteen-year-old Trethewey, who was finishing her freshman year at the University of Georgia (UGA) in Athens, where she was an English major and a varsity cheerleader, turned to writing poetry to deal with her grief.

Trethewey completed her B.A. degree at UGA in 1989, and in 1991 she earned an M.A. degree in English and creative writing at Hollins College (later Hollins University) in Roanoke, Virginia, where she studied with her father, a professor there. By the time she earned her M.F.A. degree from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1995, Trethewey was starting to publish, and her work has since appeared in the country’s most prestigious literary journals and anthologies, including The Best American Poetry.

Photograph by Sarah E. McKee, New Georgia Encyclopedia

Trethewey took her first teaching job as an assistant professor of English at Auburn University in Auburn, Alabama, in 1997. In 2001 she joined the faculty at Emory University in Atlanta, where she held the Phillis Wheatley Distinguished Chair in Poetry. In 2005-6 she served as the Lehman Brady Visiting Joint Chair Professor in Documentary and American Studies at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. In 2017, after spending fifteen years as a faculty member at Emory, Trethewey accepted an appointment at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Trethewey was the fourth African American poet, and UGA’s first graduate outside of journalism, to win a Pulitzer Prize. In early 2008 she received the Mississippi Governor’s Award for literary excellence, and later that year she was named Georgia Woman of the Year by the Georgia Commission on Women. In 2011 she was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.

Mississippi named Trethewey state poet laureate in 2012, and that same year she began her tenure as U.S. poet laureate. During her second term she launched a feature called “Where Poetry Lives” on the PBS NewsHour Poetry Series.

Trethewey is married to Brett Gadsden, who teaches history at Northwestern.

Books

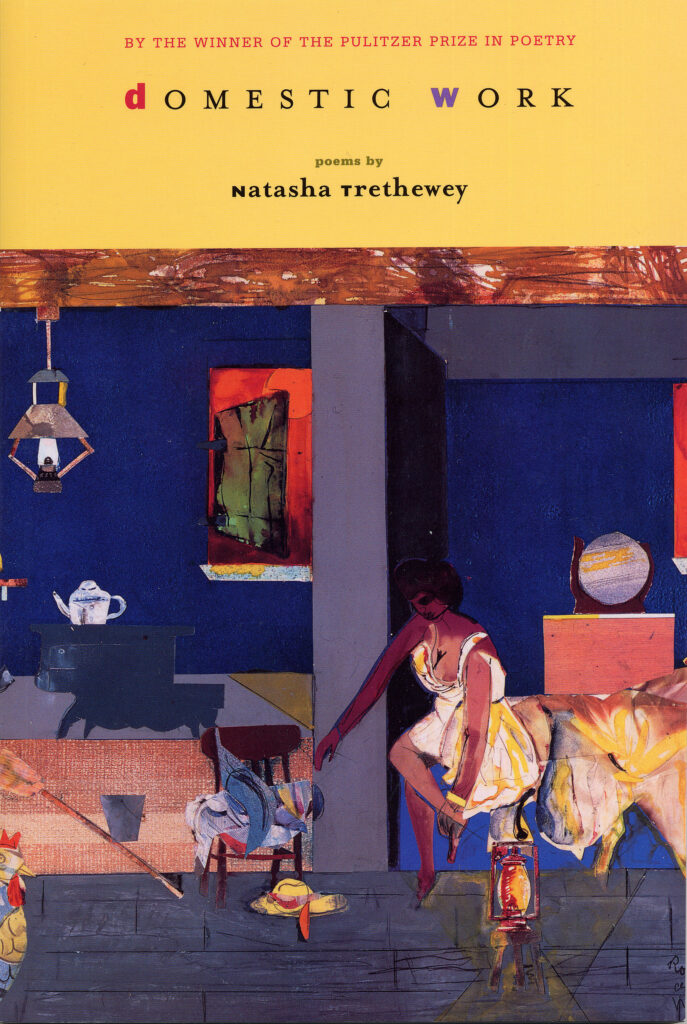

In 1999, Trethewey’s watershed year, Pulitzer Prize winner and former U.S. poet laureate Rita Dove selected the manuscript for Domestic Work as the winner of the inaugural Cave Canem Prize, an annual award for the best first collection of poems by an African American poet. The collection was published the following year by Graywolf Press, and in 2001 the book won a Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Book Prize and the Lillian Smith Book Award (named for Georgia writer Lillian Smith and administered by the Southern Regional Council).

Although Domestic Work began as Trethewey’s homage to her maternal grandmother’s lifelong labors, the embedding of personal particulars within a historical context transforms the work into a portrait of a generation, in poems with a distinct musicality. In “Three Photographs,” one of several poems based on old photographs, the viewer is compelled to witness for those unable to speak for themselves: “The eyes of eight women / I don’t know / stare out from this photograph / saying remember.”

Trethewey mined her own experiences as a mixed-race woman for her second book, Bellocq’s Ophelia (2002), based on E. J. Bellocq’s early-twentieth-century photographs of prostitutes in the infamous Storyville District of New Orleans. Written mostly in the form of letters or diary entries by the imagined Ophelia, the poems envision her as an object caught in the monocle of a scrutinizing white male customer, as a subject framed in Bellocq’s lens, and as a woman beginning to grasp her role in shaping her own identity. Winner of the 2003 Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Book Prize, Bellocq’s Ophelia was a finalist for both the Academy of American Poets’ James Laughlin and Lenore Marshall prizes, and was named a 2003 Notable Book by the American Library Association.

Trethewey’s attention to lost histories finds full expression in the Pulitzer Prize–winning Native Guard (2006). The collection’s three parts—elegies to the poet’s dead mother, a ten-sonnet persona poem in the voice of a Black soldier fighting in the Civil War (1861-65), and a final section of autobiographical poems—emerge from Trethewey’s desire to remedy historical amnesias. As an adult, Trethewey learned that the guards of the Confederate prison at Mississippi’s Ship Island were the Louisiana Native Guards, the Union army’s first official all-Black regiment to serve in the Civil War—a fact never mentioned by tour guides or historical plaques during her annual childhood visits. The link between this historical erasure and her mother’s death became clear to Trethewey when she composed “Monument,” a poem about her mother’s virtually unmarked grave in Gulfport:

At my mother’s grave, ants streamed in

and out like arteries, a tiny hill rising

above her untended plot.

………………….

Believe me when I say

I’ve tried not to begrudge them

their industry, this reminder of what

I haven’t done. Even now,

the mound is a blister on my heart,

a red and humming swarm.

As a monument not only for the forgotten soldiers but also for the poet’s mother and for Trethewey’s own conflicted relationship to the South, Native Guard exemplifies this writer’s ambitious project to testify to “those stories often left to silence or oblivion, the gaps within the stories that we are told, both in the larger public historical records and in our family histories as well.”

In 2010 the University of Georgia Press published Trethewey’s Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, a narrative chronicling the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 on her childhood home of Gulfport, as well as on the life of her family. Her fourth volume of poetry, Thrall, was published in 2012.