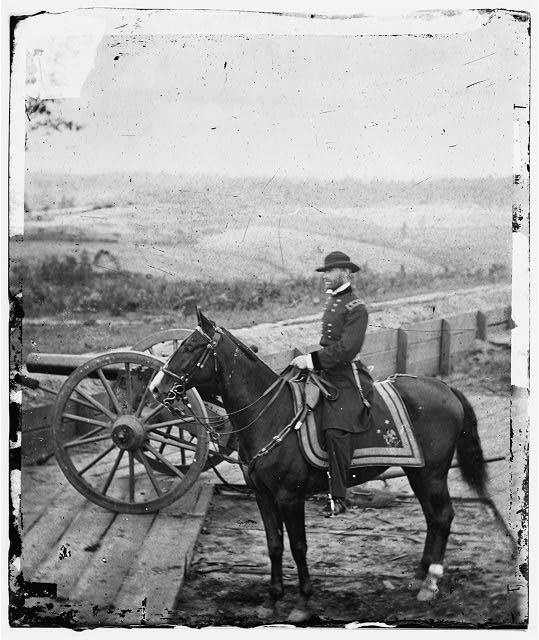

The presence of Union general William T. Sherman in Georgia during the Civil War (1861-65) has inspired numerous novels. These fictional accounts, some obscure and some quite prominent, have centered on characters caught up in either the Atlanta campaign, during the spring and summer of 1864, or the subsequent March to the Sea, in the late fall of that year.

Perhaps one reason that these events have attracted so many novelists is that both the campaign and the march involved interactions among many different types of people, including soldiers and civilians, Northerners and Southerners, Blacks and whites, and the rich and the poor. Such interactions provide ample fodder for dramatic situations and compelling characters, as the works discussed here demonstrate. Both individually and collectively, these novels reflect the tensions, traumas, and social complexities of an invading force whose presence caused tremendous upheaval in the lives of Southerners, both urban and rural, in its path.

Probably the first fictional account of Sherman’s march appears in the Joel Chandler Harris work On the Plantation: A Story of a Georgia Boy’s Adventures during the War (1892). Harris’s semiautobiographical account, drawn from his experiences as a boy on Turnwold Plantation in Putnam County, includes a dramatic description of Union forces raiding the county and the plantation early in the March to the Sea. Perhaps the most curious novel dealing with the war in Georgia during 1864 is Goldie’s Inheritance: A Story of the Siege of Atlanta (1903), by Vermont writer Louisa Bailey Whitney. For the novel Whitney drew heavily on her sister Cyrena Bailey Stone’s diary of the war years in Atlanta. The diary came to light after historian Thomas G. Dyer at the University of Georgia discovered it to be a key piece of source material for the history of the Atlanta community of “secret Yankees,” or Unionists, of which Stone was a part.

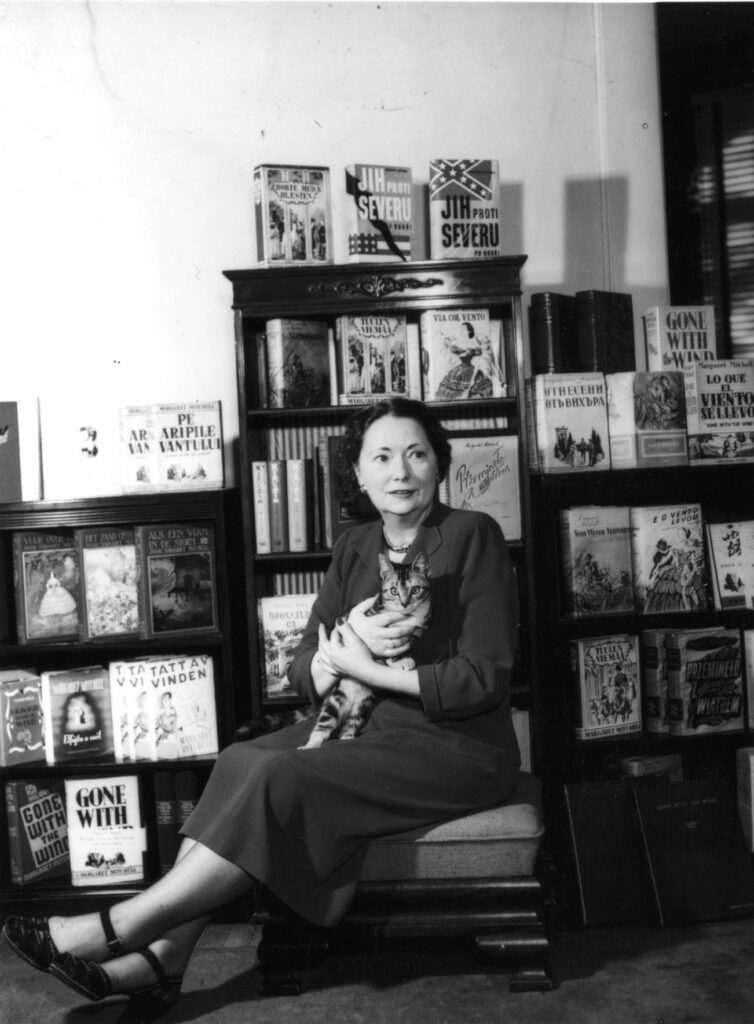

Certainly the most popular account of the Atlanta siege and its aftermath occurs in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind (1936). The burning of Atlanta and the efforts of protagonist Scarlett O’Hara to flee the city make for some of the most dramatic sequences in both the novel and its 1939 film adaptation. (Kentucky writer Caroline Gordon made the Battle of Chickamauga, fought in Walker County in 1863, the centerpiece of her novel None Shall Look Back. Published in 1937 and thus overshadowed by Gone With the Wind 's appearance a year earlier, it remains a critically acclaimed work that focuses on the plight of two families in Kentucky and Georgia.)

In more recent years several writers have constructed novels based on the events of 1864 in Georgia. Cynthia Bass’s short novel Sherman’s March (1994) recounts the Union army’s trek across the state through the voices of three protagonists: a Union captain from Illinois, a young Confederate widow on a plantation near Milledgeville, and Sherman himself. Each character narrates a third of the book.

Two novels, Daniel R. Burow’s well-regarded Sound of the Bugle: The Adventures of Hans Schmidt (1973) and John Jakes’s Savannah; or A Gift for Mr. Lincoln (2004), are set in Savannah. Both novels recreate the turmoil in and around the city as the Union army approached and ultimately occupied it, and both focus on the experiences of local residents, Black and white, who are forced to interact with the Northern invaders in a variety of circumstances, some more hostile than others.

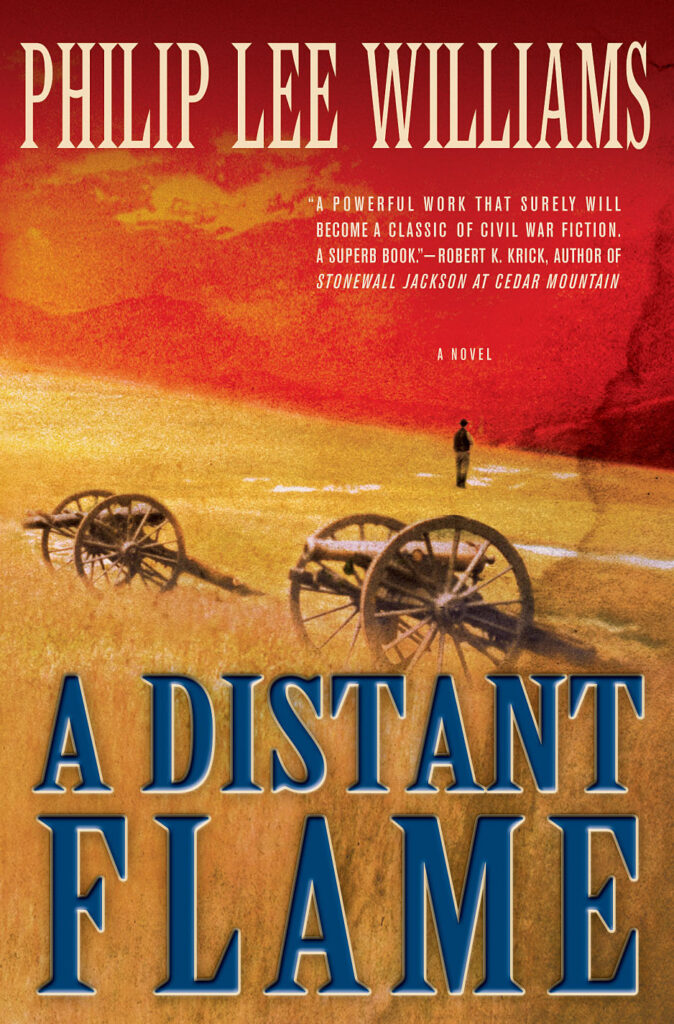

Two novels published early in the twenty-first century have been particularly well received and are recognized as among the most accomplished and historically accurate treatments of the subject. Athens-based novelist Philip Lee Williams’s A Distant Flame (2004) is told from the viewpoint of Georgia natives, many of whom experience the conflict on their home turf. E. L. Doctorow’s The March (2005), told primarily from a Northern viewpoint, focuses on the campaign in the southern half of Georgia and beyond. Very different in terms of character and plot, these novels complement each other. While both offer graphic, powerful battle scenes, Williams effectively portrays battle from the individual soldiers’ points of view, while Doctorow gives a deeper, broader sense of war as a phenomenon.

A Distant Flame

Philip Lee Williams’s A Distant Flame is about the struggle of an old man, Charlie Merrill, to make sense of his memories and his life. The novel received the 2004 Michael Shaara Prize for Civil War Fiction, and in 2005 was listed among the Georgia Center for the Book’s top twenty-five notable books by Georgia authors.

A Confederate veteran and small-town newspaper editor, Charlie is known nationally for his columns and books. Through alternating chapters set in 1861-63, 1864, and 1914, Williams’s novel recounts a love story, a war story, and Charlie’s later reflections on these events. The novel’s final chapter is set in 1918.

The chapters covering 1861-63 follow the relationship between Charlie, who lives in fictional Branton, Georgia, and Sarah, a girl from Boston, Massachusetts, who has come to live with her uncle in Branton while her parents are divorcing. (Branton is loosely based on Madison, where Williams grew up.) Their romance ends in 1864, when Sarah leaves for England to live with her father. The chapters set in 1864 recount Charlie’s experiences as a soldier and sharpshooter with the Confederate army as it retreats before Sherman’s forces during the Atlanta campaign. The remaining chapters, set in 1914, are told from the vantage point of Charlie, now an old man, as he prepares to deliver a speech commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Atlanta. While doing so he recalls his wartime experiences and his affair with Sarah.

Although the novel focuses mainly on the white inhabitants of a small Georgia town, it also documents the social realities of the times in which they lived, including the institution of slavery. Williams shows a close relationship between the Merrill family and some of their enslaved workers, but he also makes clear that the lives of enslaved people were severely constrained. As an old man, Charlie is convinced that slavery was an evil.

Williams’s research into the Civil War never overwhelms the novel but provides a rich historical context. In an afterword Williams describes how he studied the way men and women from that era talked and thought by reading letters, journals, diaries, and other accounts from those years.

A Distant Flame, with its credible, intense, and realistic portrayals of battle, conveys an understanding of the unpleasant and unworldly horrors of war, not only the violence and carnage but also the disease-ridden conditions in which solders lived and often died.

The March

One of America’s most acclaimed historical novelists, E. L. Doctorow offers The March as his first work set during the Civil War era. Focusing on Sherman’s march to the sea and subsequent foray into the Carolinas, The March won the National Book Critics Circle Award for 2005 and the Pen/Faulkner Award for 2006. (Only the first third of the novel is set in Georgia.)

The narrative method in The March is reminiscent of Doctorow’s best-known novel, Ragtime (1975), in that he combines historical details gleaned from meticulous research with an array of fictional and nonfictional characters, both soldiers and civilians. The stories of the various participants in the march are interwoven, demonstrating the varied impact of Sherman’s forces as they passed through Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

Although no single protagonist guides the novel, several important characters emerge: the enslaved girl Pearl, who follows the Northern troops as they leave Macon; Emily Thompson, the daughter of a Southern patriarch who dies while Northern soldiers occupy their house; Dr. Sartorius, a brilliant Northern field surgeon devoid of feeling; a British reporter; a photographer; and Arly and Will, two no-account Confederate soldiers who change allegiance from North to South and back depending on the needs of the moment. And, of course, there is Sherman himself.

Some of the characters are present in The March from beginning to end; others enter for a time and are killed or simply fall out of view. All engage in a continual process of personal redefinition as their circumstances change, especially as a result of the war. For the Southern characters, change often requires adjustment to the destruction of their familiar world; they often become entirely different people, engaging in behaviors that they would never have considered prior to Sherman’s arrival. To the Northern characters, change often means confronting personal successes and failures as the war progresses.

Doctorow portrays the march as loosely organized anarchy. Sherman has some control over the direction in which his troops move but little control over their individual actions. (This is especially evident when the troops ignore his orders and burn Columbia, South Carolina.) Sherman is the book’s most fascinating character. He desires greatness, wants recognition for his achievements, and feels overlooked, especially when commanding officers blame him for a disastrous battle over which he had little control. Although Doctorow might have paid Sherman more attention in this novel, to have done so would have violated its essential premise and narrative structure, which allows none of its characters prominence over the others.

Doctorow’s basic theme in The March is that war is evil. It alters or destroys lives. It is a naturalistic force that destroys landscapes and nations. It roils on in chaos and disrepute, and people, voluntarily or not, become caught up in it. Although the novel occasionally acknowledges such political and historical causes of the Civil War as slavery, more often than not it depicts war as an event with little connection to historical causes and political movements.