Atlanta native Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel of the Civil War (1861-65) and Reconstruction in Georgia, Gone With the Wind, occupies an important place in any history of twentieth-century American literature. Dismissed by most academic literary critics for being uneven, flawed, and conventionally written in an age marked by literary experimentation, and attacked by some cultural commentators as promulgating racist myths and undermining the very foundations of its basically feminist paradigm, the best-selling novel of the twentieth century continues to withstand its detractors.

Influences and Historical Background

Upon its publication, reviewers drew comparisons with William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair and Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Margaret Mitchell claimed not to have read Thackeray’s novel until after she had completed her Civil War saga and confessed her inability ever to get very far in Tolstoy’s monumental work. She did admit her saturation in Charles Dickens and her sense that her work was a “’Victorian’ type novel.” Mitchell chose an epic moment in American history and never flinched in bringing it to life on a grand scale; a creative energy reminiscent of the nineteenth century drives the work. From the memorable first sentence through the Twelve Oaks barbecue on the eve of the war, the fall of Atlanta, Scarlett O’Hara’s unforgettable journey back home to Tara, and her beginning struggles during Reconstruction, Mitchell’s narrative power (at the very top of its form) propels the reader through the limning of a culture (its grace and color and folly and weakness), a vivid evocation of the cauldron of war, and a bitter picture of the devastation following.

The author spoke often of her research in accounts and memoirs of the period, but probably more important was her knowing people who had lived through the era. A child naturally drawn to old people and to the great drama of her region, Mitchell had gone horseback riding with Confederate veterans, sat listening in the parlors of faded belles, and taken every literary advantage of her exposure to the past. The result is a detailed and realistic sense of the texture of the period—Scarlett O’Hara’s green morocco slippers, the bright rag rugs in her bedroom at Tara, Melanie Hamilton’s black lace mittens—that leads to the capturing of color and movement in great scenes like the Twelve Oaks barbecue and the ball in Atlanta. Alternating with such scenes are remarkably evocative descriptions of the landscape’s calm beauty.

Characters and Setting

Though her four major characters have now become stereotypes, when she drew them, with the exception of the moody Rhett Butler, they were not. Scarlett is a full-blooded woman, selfish, deluded, conflicted, but driven by her own strength of will. Melanie is far from the foolishly duped Amelia of Thackeray’s novel. Underlying her sweetness and Christian charity is enormous strength and purpose, and the Hamlet-like Ashley Wilkes is not the beau ideal of the southern planter or Confederate stalwart.

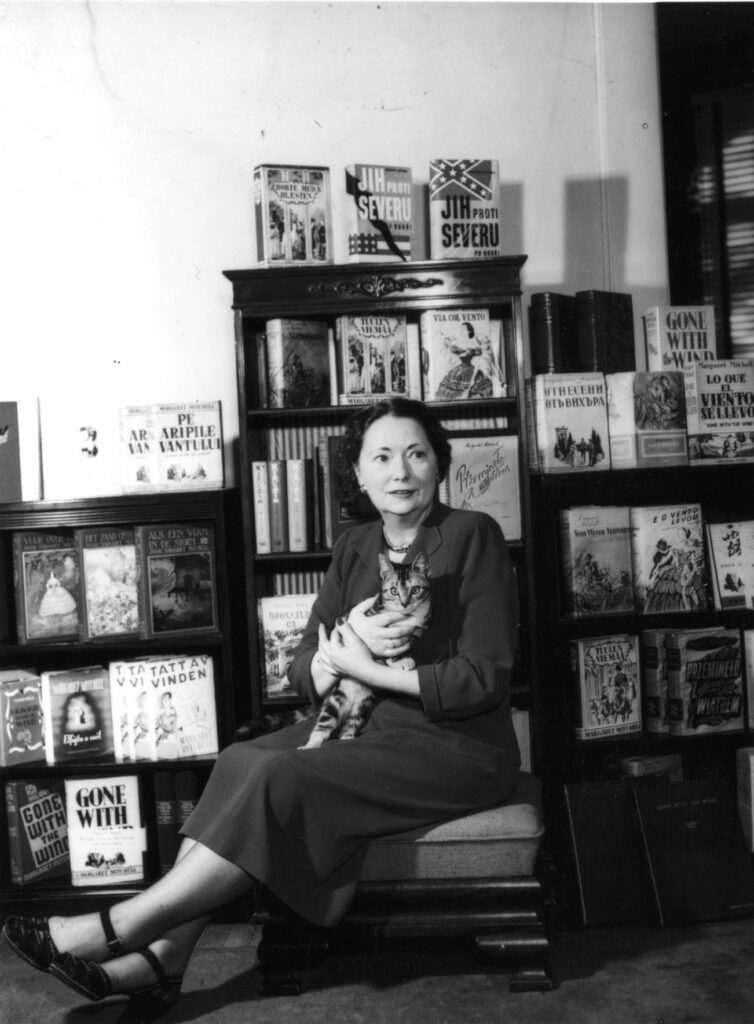

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Mitchell’s upland Georgia is also not the dreamy land of a Thomas Nelson Page plantation novel. She is insightful on the social structure, its closeness to pioneer days, and its mixture of old bloodlines and new men. She is astute about the violence lying not far submerged beneath the surface of all classes. She is unsentimental about the Lost Cause, tracing its origins to unreconstructed women, not to the men who fought the war. And she is remarkably good as a novelist of manners, understanding the mores and customs of the culture she is examining and bringing them skillfully into play.

Thematic Motifs

Like many of the omnibus novels of the nineteenth century that influenced it, Gone With the Wind is a powerful, flawed, uneven, and sometimes disturbing novel that explores diverse facets of the human experience.

Sexuality

The novel contains the stuff of great romance. Two great loves—one a misplaced, deluded infatuation, and the other a thwarted union of two passionate spirits—share equal focus with the story of people swept along by the forces of history. Additionally, the novel is sexually charged. Scarlett’s self-affirming attraction to Ashley could not be sustained were she not given proof at two significant points in the novel that he responds to her sexually, that he wants, in his own phrase, to “take” her. The powerful sexual chemistry dramatized between Scarlett and Rhett provides a running tension of the novel, countered as it is by Scarlett’s incredibly dogged and willful attachment to her first romantic ideal. It is testimony to Mitchell’s skill that these basic sexual and emotional tensions could be sustained for 1,037 pages in the original Macmillan edition.

Survival

Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind is one of the great novels of survival, and therein lies much of its appeal. In chapter 43 Mitchell gives to Rhett Butler a version of the speech that we know now her own mother had given her when she was a child. He is speaking, in the war’s aftermath, about Ashley Wilkes:

Whenever the world up-ends, his kind is the first to perish. And why not? They don’t deserve to survive because they won’t fight—don’t know how to fight. This isn’t the first time the world’s been upside down and it won’t be the last. . . . But there are always a hardy few who come through and, given time, they are right back where they were before the world turned over.

The Darwinian message is made flesh in Scarlett O’Hara. But Mitchell is clear-sighted enough to see that a moral and emotional price is often paid for survival against great odds. That fact is borne out in a number of ways in the novel’s conclusion.

Feminism

Mitchell also wrote a distinctly feminist novel. She sounds the note early with the narrator’s comment that “at no time, before or since, had so low a premium been placed on feminine naturalness,” and she mercilessly exposes a southern patriarchy that requires that women be flatteringly subservient to males, no matter how much less intelligent and capable. But even more telling than its overtly repeated feminist message, it is a novel dominated by strong women—Scarlett, Melanie, Ellen O’Hara, Mrs. Tarleton, Grandma Fontaine, Mrs. Meade, and Mammy. Mitchell takes pains to show the spine of a southern matriarchy secretly underlying a patriarchy.

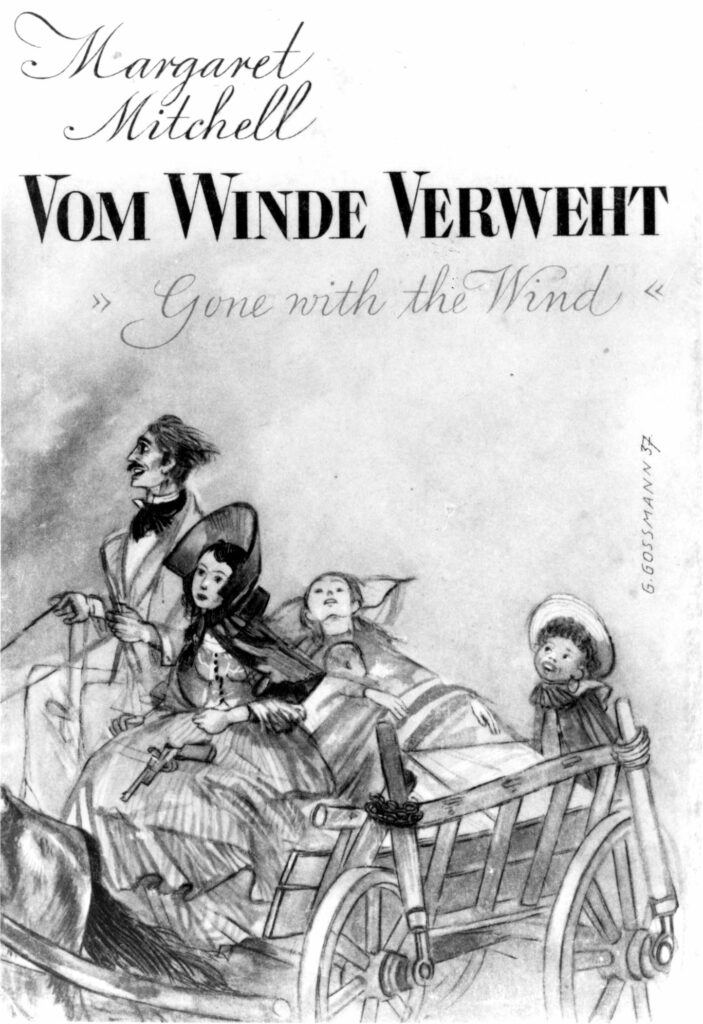

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Some critics have argued that Scarlett’s feminist success story is undercut by a sexual desire to be engulfed and dominated. Mitchell delves into human sexuality with all of its complications. Ashley Wilkes’s own fear of being passionately released but then engulfed and dominated by Scarlett is a case in point: “you would want all of a man,” he laments. In Mitchell’s failure to bend sexual desire to some clinically theorized, balanced, emotionally healthy structure, she is a modern writer.

Representations of African Americans

The inherent racism of the novel is more difficult to defend. Characteristic of her generation of southerners is Mitchell’s unquestioning acceptance of the essential inferiority of African Americans, whom she presents, in a few distasteful instances, in nonhuman terms. Melded with that prejudice, contradictorily, is evidence of her great respect for some members of the race. Such a bifurcated vision is the very dilemma that Mississippi author William Faulkner wrestled with his entire writing career. In the novel Mitchell merely accepts the institution of slavery and fails to recognize the strength and courage of those who rebelled against their enslavement.

What she presents well is an array of portraits of an uneducated African American peasantry, ranging from the nobility, shrewdness, loyalty, and affection of Mammy to the foolishness of Prissy. Like William Shakespeare, Mitchell writes fools among all classes, and very few have yet criticized her portrayal of Honey Wilkes. Margaret Mitchell was proud of the fact that she had tried to convey accurately the speech of the old African Americans of her acquaintance without resorting to the entangled dialect of Joel Chandler Harris, and she reacted against all the stock figures, white and Black, of the sentimental plantation novels that preceded Gone With the Wind.

Mitchell is most open to criticism in the last third of the novel. The narrative drive diminishes, returning only in fits and starts. Historical background is too often telegraphed, rather than blended, into the fabric of the novel. And Mitchell appears to succumb to a nightmare vision of white female purity under attack by Black bestiality only to be saved by the Ku Klux Klan. The model here, which Mitchell halfway acknowledges in a letter, is Thomas Dixon’s racist novel The Clansman (1905), made into what is often regarded as the first masterpiece of American cinema, The Birth of a Nation, in 1915—both works that praise the reemergence of the Klan in the twentieth century.

Mitchell’s conflicted sensibility is apparent when she has Scarlett comment about one such incident, “Probably the girl hadn’t been raped after all. Probably she’d just been frightened silly.” And she has Scarlett deliberately and foolishly expose herself to danger, against all advice, by her stubborn drive through Shantytown, where the homeless and desperate have collected. And even though the Black man’s assault upon her seems closer to a robbery than a rape attempt, still by introducing the situation of the imperiled white female threatened by the powerful Black man and the resulting Klan vengeance, Mitchell’s novel invites the same criticism heaped on Dixon’s work.

Conclusion

With its richly detailed evocation of a former age, its narrative engagement, its compelling portrait of the archetypal human instinct for survival, and its reflection of the contrariness of romantic dreams, Gone With the Wind continues to capture, entertain, excite, and sometimes exasperate readers. As well as being a gripping novel of epic proportions, the book is valuable as a historical document—though one that must be carefully read. A vivid record of a segment of life in the nineteenth-century South, the novel is also the record of a twentieth-century sensibility’s engagement with the region’s past.