In Patriotic Gore (1962), his classic study of Civil War (1861-65) literature, the literary critic Edmund Wilson asks, “Has there ever been another historical crisis of the magnitude of 1861-1865 in which so many people were so articulate?” Historian Louis Masur later made the same point, stating that “the Civil War was a written war,” one in which hundreds of participants and observers “struggled to capture the texture of the extraordinary and the everyday.”

Georgians were certainly among those for whom the war became a “written war,” and their accounts of what they experienced or observed took the form of letters; of diaries and journals, with entries made on a fairly regular basis during the war; and of memoirs and reminiscences, produced in hindsight, often many years after the war. Firsthand accounts in all these genres were written by soldiers as well as civilians, women as well as men, Blacks as well as whites, collectively offering a remarkably multifaceted view of how the war was perceived and felt by both Georgians and those brought to the state’s battlefronts and home fronts through a wide spectrum of circumstances.

A significant number of these accounts have made their way into print over the century and a half since the Civil War ended, and in numbers unmatched by any other war in American history. While some journals and diaries were published almost immediately after the war’s end, it was in the mid-1870s that most memoirs began to be published, at rates that continued unabated until well after the turn of the twentieth century. Much of this trend was in response to a strong public interest in the military history of the war, which emerged in the late nineteenth century in both the North and the South, and also to the full flowering of the “Lost Cause” in the South, in which white southerners sought to interpret the conflict in ways that justified both how and why the war was fought. The centennial of the war, from 1961 to 1965, inspired the publication of another round of wartime chronicles, many of which were reprinted, while others were published for the first time. That trend has been ongoing since, as newly found diaries, collections of letters, and other manuscripts continue to be edited and published in book form.

Atlanta Campaign

A number of diaries and memoirs by local residents capture the drama of the war in Atlanta, including the fall of the city and Union general William T. Sherman’s subsequent occupation in 1864.

Perhaps the most widely read of all memoirs by a Confederate soldier is Sam Watkins’s Co. Aytch (1952), which offers a comprehensive and personal account of the Atlanta campaign from a Southern participant. An enlistee from Tennessee, Watkins spent the entire war in Confederate gray, and yet he claimed to “only give a few sketches and incidents that came under the observation of a 'high private’ in the rear ranks of the rebel army.” He first came into Georgia to fight at the Battle of Chickamauga and returned to fight in almost every other major engagement in the state, including those at Resaca, Kennesaw Mountain, Atlanta, and Jonesboro. (His descriptions of the destruction and death he witnessed at Chickamauga and at the “Dead Angle” on Kennesaw Mountain are among the most harrowing that have survived from any military eyewitness.) Watkins’s narrative first appeared in his hometown newspaper in 1881 and 1882, and soon thereafter 2,000 copies were published, primarily for local consumption. During the Civil War centennial, a new edition was published, and it has never been out of print since.

Sarah “Sallie” Conley Clayton’s memoir, long held in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society, was published in 1999 under the title Requiem for a Lost City. The memoir provides a lively description of Clayton’s life as an adolescent in Atlanta and the increasing tensions and hardships she and her wealthy family endured. She offers a detailed account of the Battle of Atlanta, which raged within sight of her home, and of her family’s subsequent expulsion from the city.

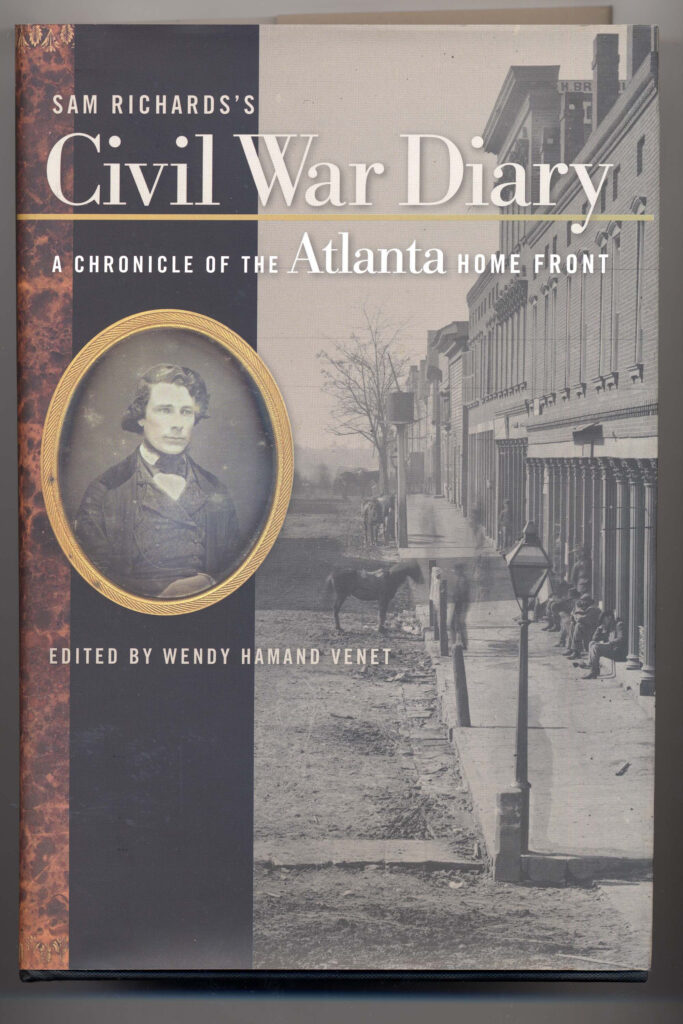

Samuel Pearce Richards, a prominent merchant, kept a diary for sixty-seven years, and his thorough coverage of the war years is considered by many to be the best surviving portrait of the Atlanta home front. Surprisingly, the diary only made its way into print in 2009. Richards, the younger brother of artist Thomas Addison Richards, moved to Atlanta from Macon after the war was under way. His diary entries offer astute commentary on Confederate economic and military policy, and the financial hardships he suffered as a result of both. He, like Clayton, wrote vividly about his forced exit from the city as well as his sojourn in New York, which lasted until he found it safe to return to Georgia in August 1865.

A very different perspective on Atlanta has also come to light in recent years. Cyrena Stone, a Vermont native who settled with her husband in Georgia in 1850, found herself part of a secret Unionist community in Atlanta when the war broke out, and she kept a diary about the experience. In 1976 that anonymous eighty-page document was sold to the University of Georgia library, where it was known simply as “Miss Abby’s Diary” until the 1990s, when historian Thomas G. Dyer discovered not only Stone’s identity but also that of many of her fellow Unionists, whom she referred to in code. From Stone’s diary, Dyer produced a full history of the underground Unionist movement, entitled Secret Yankees, which details a much different response to the Battle of Atlanta and Sherman’s occupation than do the chronicles of local Confederates.

Sherman’s March

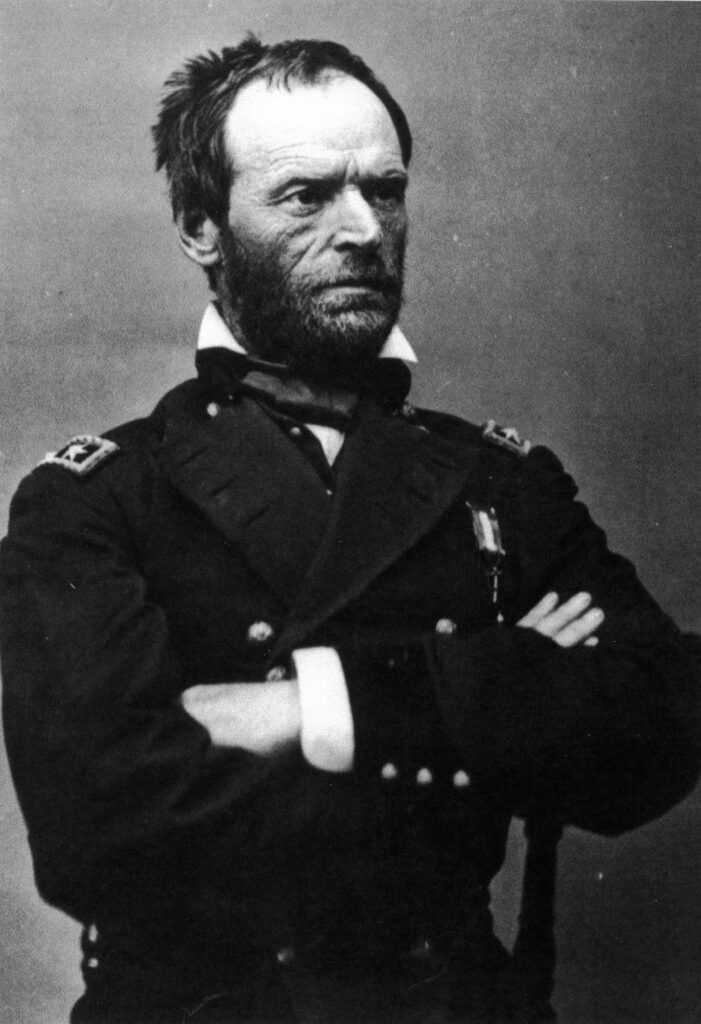

There are dozens of diaries and memoirs by Union troops who marched to the sea under Sherman. Historian Joseph Glatthaar wrote a book on the march based almost entirely on those firsthand accounts, including more than sixty diaries and reminiscences by enlisted men and junior officers. From their writings, Glatthaar was able to concentrate much of his analysis on their attitudes toward Sherman, toward his “total war” approach, and toward the many civilians and enslaved African Americans they encountered en route.

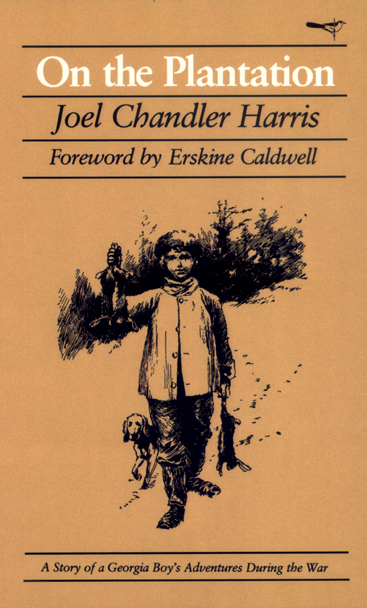

Among the best-known civilian perspectives on Sherman’s march are those of Joel Chandler Harris, Eliza Frances Andrews, and Dolly Sumner Lunt (Burge). Harris’s thinly fictionalized On the Plantation (1892) includes a curiously benign account of the movement of Sherman’s troops through Putnam County and the ransacking of Turnwold Plantation, where he lived and worked. Andrews’s classic War-Time Journal of a Georgia Girl, 1864-1865 (1908) recounts her harrowing retreat from her home in Washington; as Union forces approached, she moved across ravaged areas to find refuge at her sister’s plantation in the southwestern part of the state. Lunt’s A Woman’s Wartime Journal (1918), reprinted under different titles since its original publication, recounts the hardships she faced in managing a plantation near Covington before, during, and after Sherman’s men moved through the area.

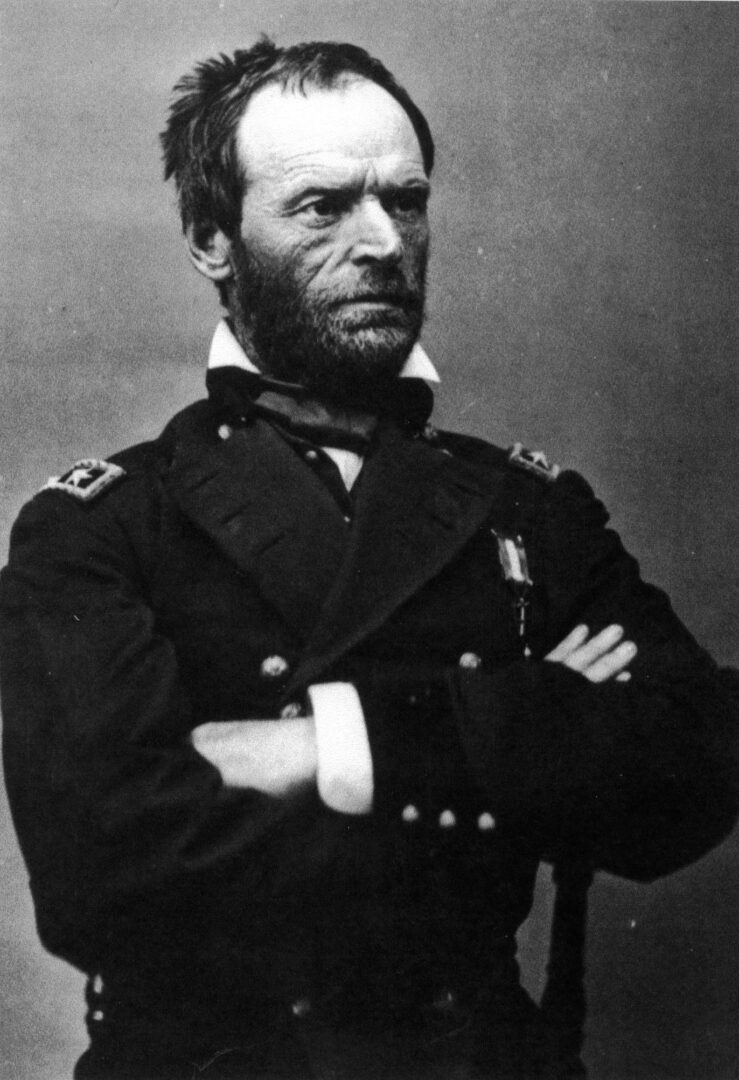

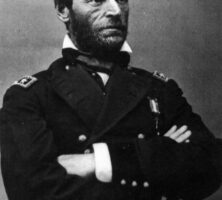

The most widely read first-person chronicle of Sherman’s activities in Georgia comes from Sherman himself. One of the first major military figures on either side to publish his account of the war, Sherman devoted more than a fourth of his memoir’s 800-plus pages to the Atlanta campaign, the March to the Sea, the occupation of Savannah, and the policies toward freedmen that he initiated there. As much a historical treatise, full of facts and figures, as a personal memoir, Sherman’s two-volume work (1875) was revised and updated twice before his death in 1891 and has appeared in numerous editions since, including several that include only the Georgia portion of the work, one of which is entitled “War Is Hell.”

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

Women on the Home Front and Battlefront

Georgia women produced some of the most significant memoirs chronicling home front activity in the state. Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas, in Augusta, wrote a journal covering the years 1848 to 1889, a far broader time frame than most; selections from her journal were published under the title The Secret Eye in 1990. Her commentary over the war years demonstrates the typical arc that many southern women experienced during the war, moving from initial enthusiasm for the Confederate cause to increasing resentment and war weariness as the conflict dragged into its third and fourth years.

Eleanor “Nellie” Kinzie Gordon, the Chicago-born wife of Savannahian William Washington Gordon II (and the mother of Juliette Gordon Low), found herself living with her in-laws when the war broke out. She spent most of the war in Georgia’s port city, while her husband served as a Confederate captain, and for much of 1862 she kept a journal. Although she was publicly supportive of the Confederate cause at the beginning of the conflict, Gordon soon became disenchanted with the war, and inconsistencies in both her writings and her actions leave historians unsure of her true wartime loyalties. Edited portions of her journal were published by the Georgia Historical Quarterly in 1986. Another revealing Unionist perspective comes from a journal kept by Louisa Fletcher, who with her husband kept a hotel on the main square in Marietta. It was published as Journal of a Landlady in 1995.

More actively engaged women have also left behind narratives describing their wartime enterprises. Susie King Taylor’s memoir is unique in that it is the only surviving wartime description by a Black Georgia woman. A freedwoman, Taylor was born on a Liberty County plantation. She escaped in 1862 and joined the ranks of coastal contrabands in South Carolina, where she became a nurse to sick and wounded Black Union troops as they moved down the coast from South Carolina, through Georgia, to Florida. She composed her account of that experience only at the turn of the twentieth century, and it appeared in print in 1902 under the title Reminiscences of My Life in Camp.

Two other nurses who served opposing armies in Georgia kept journals that were later published. Scotland native Kate Cumming traveled with the Army of Tennessee into Georgia and documented her work as a hospital matron in A Journal of Hospital Life in the Confederate Army (1866). It has appeared in multiple editions since then. Fannie Oslin Jackson, a Unionist in the north Georgia mountains, established a field hospital for Union troops on her farm during the fighting at nearby Resaca, and then followed the troops with a mobile hospital operation as they moved toward Atlanta. Her brief memoir of that experience, entitled On Both Sides of the Line, was composed soon after the war but not published until 1989.

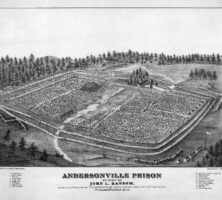

Andersonville Prison

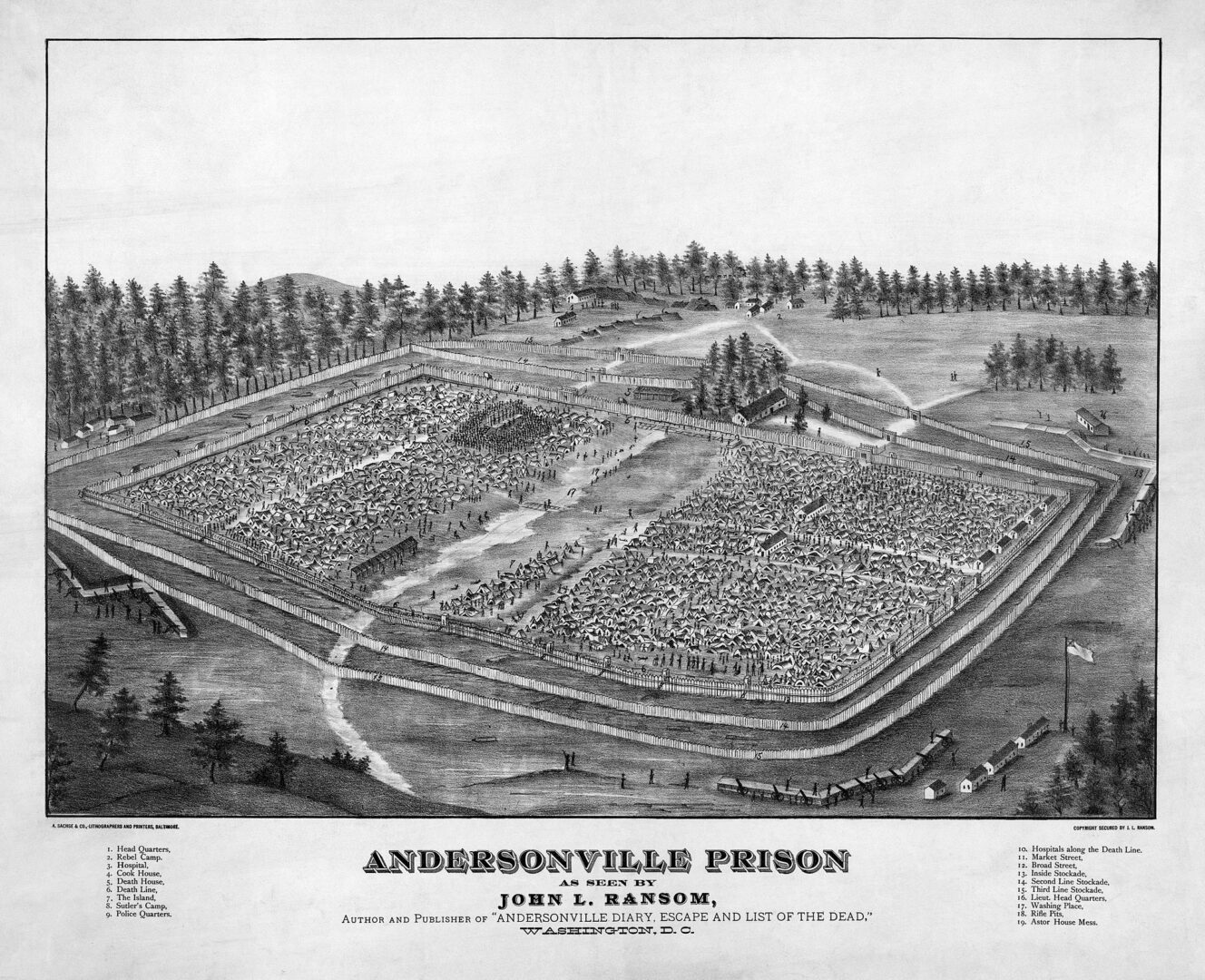

In addition to Sherman and his troops, other outsiders who experienced much of the war in Georgia were prisoners at Camp Sumter, known as Andersonville Prison, and other prisoner-of-war camps in the state. Dozens of different accounts of life at Andersonville, the most notorious of Confederate prison camps, appeared soon after the war, some as memoirs, many as published diaries and journals. These publications served as part of a propaganda campaign condemning the treatment of those held at Andersonville and demonizing Henry Wirz, the commandant whom many held responsible for the deplorable conditions there. The first of these publications, Connecticut native Robert Kellogg’s Life and Death in Rebel Prisons, appeared late in 1865. In it, Kellogg states his intention of “kindl[ing] the fires of indignation” throughout the North for the treatment of Union troops, particularly at Andersonville, where he spent several months in 1864.

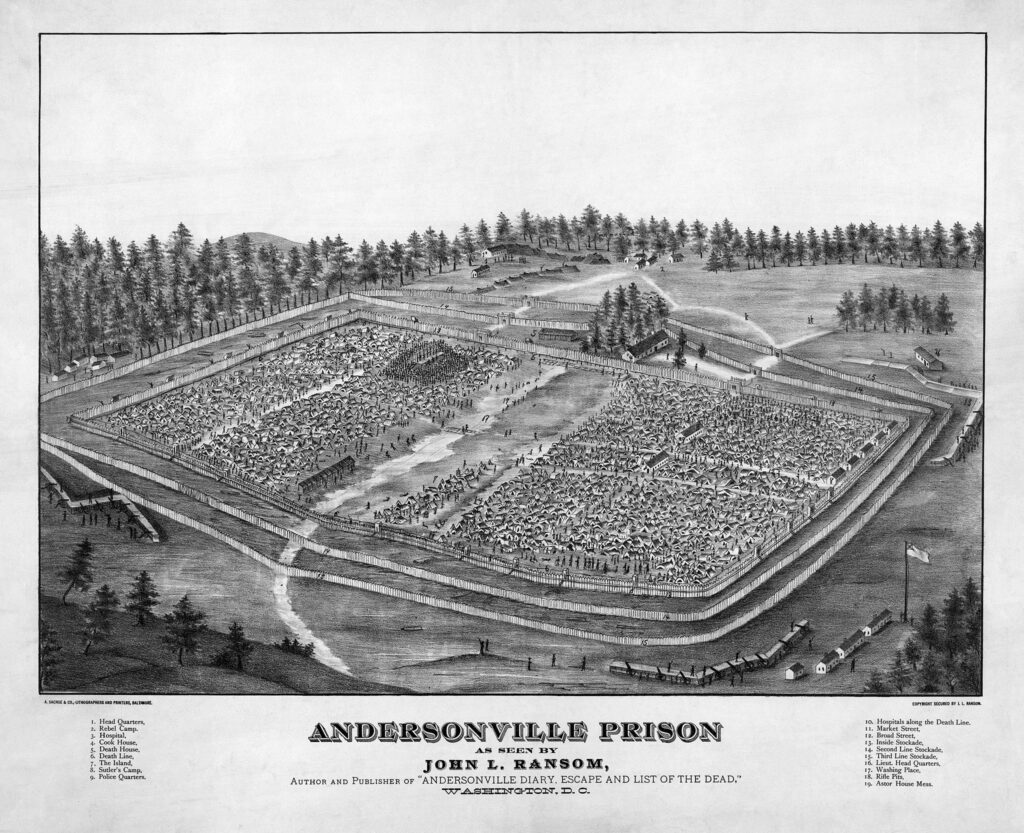

Perhaps the most widely reproduced prisoner’s account of Andersonville Prison is Michigan sergeant John Ransom’s Andersonville Diary, which has appeared in several editions (and under different titles) since its original publication in 1881. Ransom was among the first prisoners brought to Andersonville and spent six months there. Inaccuracies in facts and dates, as well as his harsh judgments of Wirz, the guards, and his fellow prisoners, have made his account suspect among historians, though the thoroughness of its coverage has made it one of the best-known narratives of life there. The graphic illustrations of the camp’s deplorable conditions included in many of these accounts added to their use as effective propaganda by both former prisoners and vengeful northern politicians seeking retribution from the South, almost to the end of the century.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Historical Value

In short, the written testimonials of those who witnessed or participated in the war in Georgia, whether on the home front, the battlefield, or in hospitals or prisons, have provided a vital part of the historical record on which scholars have drawn to recreate the struggle’s human dimension from multiple perspectives. For soldiers, especially, their own accounts of battlefield action provide a sense of the confusion, the fear, the exhilaration, and the horror of warfare far better than do official records and other traditional military histories (which is why the best military histories now so often incorporate these firsthand accounts into their narratives). These personal accounts also reveal much about issues of shifting morale among both soldiers and civilians, as well as relationships between those two groups; of complex and sometime ambivalent loyalties; and of how individuals understood, remembered, and interpreted the most momentous period in their lives.