The “Fabulous” Fox Theatre, an awe-inspiring brick structure of mixed architectural motifs, has towered over the corner of Peachtree Street at Ponce de Leon Avenue in Atlanta since 1929.

Its unique cream- and buff-colored ribbons, arched doorways, minarets, and domes all combine to make the Fox an architectural illusion—lending it the appearance of a cluster of small buildings. In reality, the Fox is one cohesive building, broken up by balconies and stairways leading to various zones of the theater, which occupies the larger part of a Midtown city block. A lone minaret guards the southwest corner, styled after the prayer towers of Islamic mosques. Repeated in miniature, it flanks the Fox’s dazzling marquee. The south arabesque façade (along Ponce de Leon Avenue) is topped with three domes. The largest is a copper onion-dome laced with a ribbed latticework and crowned with the Islamic half-moon crescent. The 140-foot theater entrance arcade off Peachtree Street resembles a magic Arabian carpet—transporting patrons out of the mundane cityscape into a land of dreams. The loggia is embellished with filigreed lamps, tile, terrazzo flooring, and elaborate stenciling and plasterworks.

Inside, the 65,000-square-foot auditorium has been designed to resemble a weathered desert tent. The Fox’s cantilevered balcony was engineered to relax some three inches at full capacity. The whole interior is a masterpiece of trompe l’oeil, with false beams, false parapets, false tents, and a false sky that replicates the designer’s idea of the night sky in the desert—spangled with tiny illuminated “stars” (eleven-watt lightbulbs shining through four-inch crystals) and veil-like clouds projected onto the ceiling. Virtually every modern heating and cooling convenience is camouflaged with faux grillwork.

The fortresslike walls of the auditorium are connected on the west side by a stately bridge lit by eight flickering lanterns. This imposing bridge forms the top of a seventy-nine-foot proscenium that frames the main house curtain, which depicts mosques and Moorish rulers in a mosaic of hand-sewn sequins and rhinestones.

Since the Great Depression, the Fox has dominated the performing arts scene in Atlanta. The Atlanta Opera (1995-2003) and Metropolitan Opera (1948-68), the Atlanta Ballet, Mick Jagger, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Beverly Sills, among other performers, have appeared on the very wide (135 feet) yet very shallow (38 feet) stage. Many films have also been shown in the theater.

The controversial Disney film Song of the South, which originally premiered at the Fox in 1946, set a first-week record when it was rereleased in 1972. Although Gone With the Wind did not premiere at the Fox (that honor went to Loew’s Grand), the theater celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the film by transforming its Peachtree façade into a reproduction of Tara.

What the Public Doesn’t See

Audiences enthusiastically applaud the pièce de résistance of the theater, the Möller Deluxe forty-two-rank pipe organ console (affectionately called “Mighty Mo” by longtime Fox-goers) rising out of the orchestra pit. What they can’t see, however, is the organ’s 3,622 pipes hidden behind two trefoil arches supported by faux balcony boxes—all designed to blend with the Moorish theme. In addition to the organ’s pipe collection, the Möller also boasts dozens of sound effects, including songbirds, sirens, a Ford horn, chimes, cymbals, and a locomotive whistle.

In addition, the Fox has a large freight elevator, a separate screening room, a broadcasting studio, a central vacuum system, and showers in its seven floors of backstage dressing rooms. It also has a clinic equipped with a hospital bed, an automatic sterilizer, and supplies to handle everything from a bruise to a broken leg.

Deep beneath the stage, the Fox seems even more massive and mysterious. A morass of boilers, fans, pipes, and ducts control the climate within the vast complex. The basement is a winding maze of corridors, passageways, and rehearsal rooms. Three distinct electric lines enter the main power room on the lowest level of the theater and furnish enough electricity to light a medium-sized city. An emergency generator assures that if all else fails, the emergency lighting system at the Fox will remain on. Until recently, the backstage walls were scratched with the names of New York City streets and avenues—a necessity for the language-diverse Metropolitan Opera cast who, through this ingenious system of “street signs,” could quickly find the stage entrance in this underground labyrinth.

History of the Fox

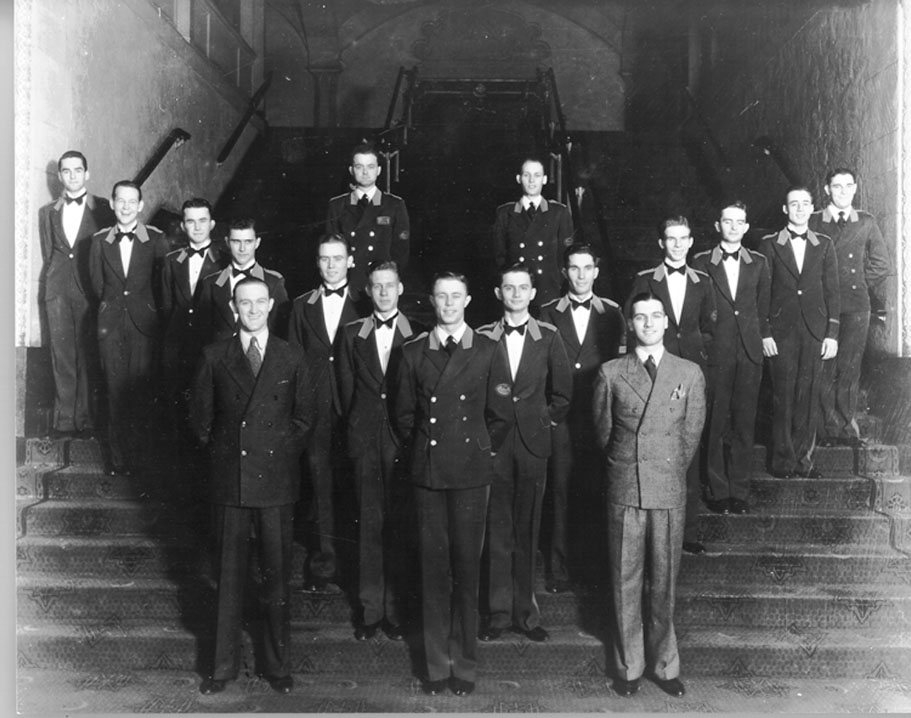

The Fox was originally intended to be Atlanta’s Yaarab Temple, the meeting hall for the Shriners, part of the Masonic organization. It was designed by the firm of Marye, Alger, and Vinour to reflect the Shriners’ Moorish theme. Soon after construction began in 1927, it became apparent that the project was too expensive for the Shriners’ budget, and they formed an agreement with the movie magnate William Fox, who leased the auditorium as a theater. Built at a cost of $2,228,670.50, the theater opened on Christmas Day 1929, just two months after the New York Stock Exchange crashed.

Despite the grim economy, the Fox gave Atlanta a sprightly Christmas present. For tickets ranging from fifteen cents to seventy-five cents, the holiday gift included a concert on the mammoth organ, a performance by the Fox Grand Orchestra, the Mickey Mouse cartoon Steamboat Willie, a sing-a-long, the Sunkist Beauties, Fox Movietone News, and the feature film Salute.

The Great Depression was not an auspicious time to launch such an ambitious project, however. By 1932 the Shriners were defaulting on their pledges, and William Fox was bankrupt. Late that year, the mortgage was foreclosed, and the theater was forced to shut down, after less than three years in operation. In the late 1930s, after passing through several hands, a new partnership bought the Fox and placed it on a sound financial footing.

During World War II (1941-45) the Fox remained open and became a popular escape route from reality to the world of make-believe. The Fox prospered as one of Atlanta’s finest movie houses from the 1940s through the 1960s, but in the 1970s the heyday of American movie palaces came to a close. The Fox was reduced to showing second-rate films.

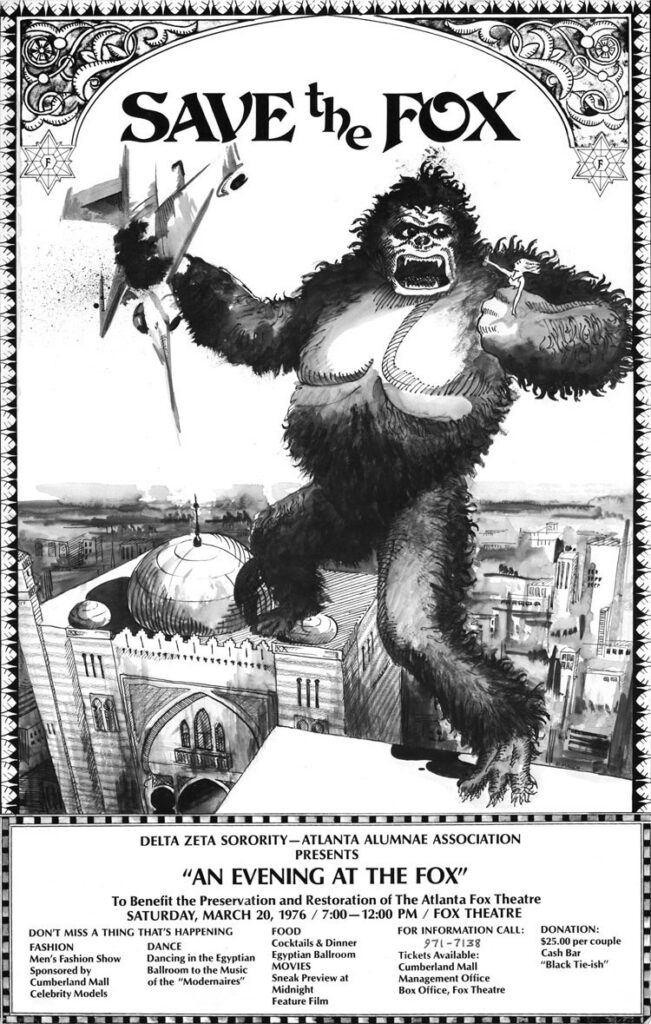

The mid-1970s was a time of explosive growth for Atlanta, and the relentless progress almost destroyed the Fox. The telephone giant Southern Bell (later BellSouth and AT&T) wanted the Fox’s desirable corner lot for its world headquarters. The city of Atlanta did not want this prestigious company to move outside the city limits, taking their employees and their lucrative tax base with them. It looked as if the Fox would be sold and demolished to make way for Southern Bell’s new corporate headquarters.

“Save the Fox”

The Fox was rescued through the efforts of Atlanta Landmarks, Inc., a nonprofit organization of interested, energetic, and committed Atlantans who purchased the property in 1975. A four-year “Save the Fox” fund-raising campaign enabled Atlanta Landmarks to pay off the mortgage in 1978. Since 1975 the Fox has operated as a multipurpose performing arts center. Rock and classical music concerts, ice shows and magic shows, Broadway musicals, dancing waters, circuses, and many organ concerts (with and without an image on the silver Cinemascope screen) are among the range of events at the theater. The Fox continues to attract nearly three-quarters of a million visitors a year, from local residents to tourists to international dignitaries, and generates millions of dollars annually for the Atlanta economy.

The theater stands today as a fiercely protected landmark and a nationally acclaimed venue, having withstood economic depression, mortgage foreclosure, bankruptcy, competition, the advent of television, and real-estate development. The Fabulous Fox has enjoyed an operating surplus every year since 1975 and is now protected as a National Historic Landmark.