One of the most recognizable features of the Atlanta skyline is Georgia’s gold-domed state capitol, located several blocks southeast of the center of downtown. Although dwarfed by nearby skyscrapers, the dome glistens from the same hill that supported the first state capitol building in Atlanta.

Early Capitol Buildings

In all, three different buildings in Atlanta have served as statehouse; the first two have been torn down. This story begins in April 1868, when Georgia held a statewide referendum to ratify a new constitution. Article 10 of the 1868 Constitution designated Atlanta as the new state capital. Shortly afterward the contents of the old Milledgeville statehouse were shipped by train to Atlanta, where there was not yet a building to house the new state government. City and county officials came to the rescue by volunteering the building then used jointly as the Atlanta City Hall and Fulton County Courthouse. Built atop a hill just south of downtown in 1854, the two-story brick structure served as Georgia’s statehouse from July 1868 to January 1869. Overcrowded conditions quickly made it impractical for this building to continue as the home of three governments.

In August 1868 Atlanta’s city council met with a legislative committee on the matter. The city proposed the construction of either an addition to city hall or the completion of the unfinished Kimball Opera House for use by the state government. The legislature chose the latter. By January 1869, the opera house was ready for occupation. The five-story brick building in downtown Atlanta served as Georgia’s state capitol for the next two decades.

Georgia’s Current Capitol

With the end of Reconstruction (1867-76), some Georgia politicians were advocating the return of the state capital to Milledgeville. When a constitutional convention met in Atlanta in 1877, the question arose as to the best location for Georgia’s capital city. Seven days after the convention assembled, Atlanta’s city council brought a resolution before the convention stipulating that:

If Atlanta is selected by the Convention as the permanent Capital of the State, and if such selection is submitted to and the same is ratified by the people, the City of Atlanta will convey to the State of Georgia any ten acres of land in or near the City of Atlanta, now unoccupied, or the square in the heart of the City, known as the City Hall Lot, containing five acres of land, and bounded by a street on every side, on which to locate and build a Capitol for the state. Second—The City of Atlanta will build for the State of Georgia on the location selected a Capitol Building as good as the old Capitol building in Milledgeville.

The convention adopted an ordinance declaring that, at the next general election, voters of the state would decide between Atlanta and Milledgeville. On December 5, 1877, voters reaffirmed Atlanta as Georgia’s capital city. Two years later, the legislature accepted Atlanta’s proposal and selected the city hall site for the new capitol. In 1881 it set the value of the old capitol building in Milledgeville at $55,625 and stipulated that if the city of Atlanta would pay this amount plus a $60,000 mortgage on the Kimball Opera House, then the state would assume the cost and responsibility of constructing a new capitol. Atlanta agreed to this condition, though it would be several years before the state was financially able to proceed with construction.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

Not until September 1883 did lawmakers appropriate $1 million for the construction of a new capitol. In the same act the legislature stipulated that the cost of construction could not exceed $1 million; that construction should be finished by January 1, 1889; and that the capitol “shall be built of granite rock and marble, as far as practicable, and that all the materials used in the construction of said building shall be those found and procured within the State of Georgia; provided, the same can be procured… as cheaply as other materials of like quality in other localities.”

A board of commissions was appointed to oversee the project. The board advertised nationally for bids and chose the design submitted by the Chicago architectural firm of Edbrooke and Burnham on the grounds that it was more academic than the others, simple yet elegant, and monumental in its appearance. The classic Renaissance style was one of “beauty, strength and harmony.” The board then selected the Toledo, Ohio, construction firm of Milesand Horn to construct the capitol, on the basis of its $862,756.75 bid. Miles and Horn, however, proposed the use of Indiana oolitic limestone as the chief building material. The board found the use of Indiana limestone to be acceptable, after determining that the use of only Georgia marble and granite was impractical and too expensive. Further, they judged Indiana to have superior facilities for quarrying and dressing the stone.

The cornerstone, all interior floors and steps, and many walls of the capitol, however, were constructed of Georgia marble. Along the sides of the walls on the second floor is Etowah marble, noted for its pink hue. In all, the marble used in the interior covered almost one and a half acres, and, ironically, cost $12,000 more than the Indiana limestone used in constructing the entire capitol. In addition, Georgia granite was used for the foundation of the building, as were some 500,000 bricks salvaged from the 1884 demolition of the old city hall and county courthouse, which had served as the first statehouse in Atlanta.

On November 13, 1884, construction on the new capitol began, although the cornerstone was not laid until September 2, 1885. Estimates of the number present to watch the setting of the marble cornerstone ranged from 6,000 to 10,000 people.

Construction of the capitol took nearly four and a half years, with approximately 250 workmen involved. During this time, large steam-powered derricks, pulleys, and rock-polishing machines were set up. Construction was completed on March 20, 1889, two months later than stipulated by the legislature. The keys to the capitol were then delivered to Governor John B. Gordon.

During construction, the Kimball Opera House had continued to serve as Georgia’s statehouse, but on July 3, 1889, the members of the Georgia General Assembly marched as a body from the Kimball building to the new capitol. On the next day, July 4, the formal dedication of the capitol took place.

Housed in the new capitol were the offices of governor, treasurer, comptroller general, commissioner of agriculture, attorney general, secretary of state, adjutant general, school commissioner, state chemist, state physician, principal keeper of the state penitentiary, the geology department, and the railroad commission. Also located in the building were the Supreme Court of Georgia, the state library, and the house and senate chambers of the General Assembly. Offices for the Speaker of the House, the clerk of the house, and the president and secretary of the senate were provided, as well as twenty-three committee rooms.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

If the capitol was only half filled in 1889, the growth of government was such that the keeper of public buildings, in his 1910 report to the legislature, was calling for the need to build an annex, which he predicted would be “an absolute necessity” within a few years. Indeed, state agencies soon began branching out to offices in downtown Atlanta. During the 1930s and 1940s, the state erected several buildings for use by state agencies, while also purchasing several existing structures for conversion into state office space.

Architecture

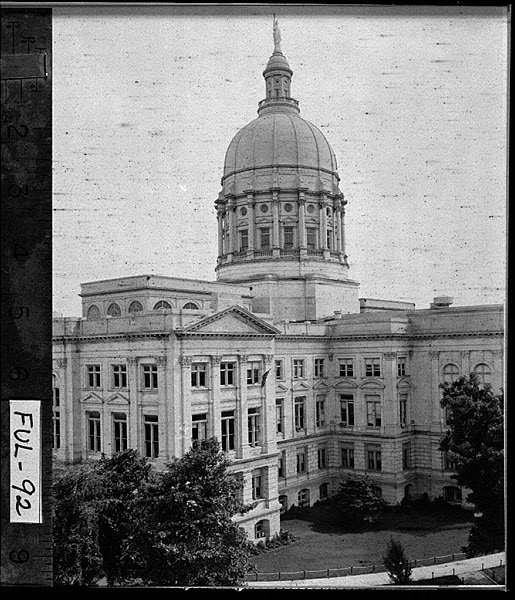

In contrast to the eighteenth-century Georgian-styled Louisville statehouse and the Gothic-inspired capitol at Milledgeville, Georgia’s current capitol is in the classic Renaissance style. Classic Renaissance arose during the 1400s and 1500s in Italy, during a period of renewed interest in the art of ancient Greece and Rome.

Photograph by Jim Everson, DVM

At the time of its construction, Georgia’s capitol was the tallest building in Atlanta, rising just over 272 feet from the ground floor. At its greatest length, it is nearly 348 feet. The outer dimensions of the dome are estimated to be approximately 75 feet in diameter. Above this dome is the observation area, which is topped by a smaller cupola, upon which a statue stands.

By contrast, the nation’s capitol in Washington, D.C., is just over 287 feet in total height and 350 feet wide. Among state capitol buildings, Georgia’s structure ranks twelfth in height. In the South, only the 34-story, 450-foot-high Louisiana capitol (built as a modern skyscraper) and the 311-foot-high Texas capitol are taller than Georgia’s.

Capitol Statue

Atop Georgia’s capitol is a statue of a woman with a torch in one hand and a sword in the other. Who she is, what she represents, and how she came to adorn the capitol is something of a mystery. In an Atlanta Constitution newspaper account written during the construction of the capitol, Captain W. H. Harrison, the secretary of the board of capitol commissioners, refers to the statue as the “Goddess of Liberty.” In recent decades, however, she has been referred to as “Miss Freedom.”

There are no records or specifications from the original installation of the statue in late 1888, so her height and weight were unknown until 2004, when the statue was removed and sent to Canada for restoration. Before being shipped north, she was weighed and measured for the first time. Miss Freedom is 22 feet tall from head to foot, with the total height from her torch to her feet being just over 26 feet. The statue, weighing 1,600 pounds, is a hollow frame covered with sheets of copper that have been painted white. At night, the torch in Miss Freedom’s hand is lit. Although it was planned from the first that a light would be placed within the torch, it was not until 1959 that this was achieved. A five-inch tube was placed through her arm and attached to a retractable trolley so that the lightbulb can be changed from the inside.

Courtesy of Georgia Info, Digital Library of Georgia.

The Dome

During a 1957 renovation of Georgia’s capitol, A. Thomas Bradbury, the architect in charge of the project, and Gordon Price, a Dahlonega-born engineer living in Atlanta, proposed that the deteriorated tin-covered dome be replaced by a more attractive and durable surface, which would then be covered by a gilding of Georgia gold.

In response to the state’s reservations about the cost, citizens from Dahlonega and Lumpkin County offered to donate the gold. Within a week, twenty ounces of gold had been pledged by citizens from an area that 129 years earlier had been the site of the nation’s first gold rush. Secretary of State Ben Fortson accepted the chairmanship of the gold dome project, which by the end of July had collected the forty-three ounces of gold estimated to be necessary for covering the dome.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

On August 4, 1958, a caravan of seven mule-drawn covered wagons left Dahlonega with the gold. Following the three-day trip to Atlanta, during which time the wagon train averaged about three miles an hour, the gold was presented to Governor Marvin Griffin in a ceremony on the steps of the capitol. Thereafter, the gold was sent to Philadelphia, where it was milled into gold leaf 1/5,000th of an inch thick, or about the thickness of a piece of tinfoil used to wrap chewing gum.

Regilding the Capitol Dome

The gold was expected to last thirty or forty years. Unfortunately, the gold was applied during the winter months, and the engineers were unaware that gold leaf does not bond properly when it is applied during cold weather. The thinness of the gold leaf also made it susceptible to wearing away from oxidation and weather.

By 1977, only nineteen years after its application, almost half of the gold was gone from the dome. Concern over the disappearing gold and the dome’s appearance led a number of Georgians and state officials to explore how the dome might be regilded. The Dahlonega–Lumpkin County Jaycees committed their organization to raising the gold for the project, as they had done in the late 1950s, with overall responsibility for regilding to be assumed by the Georgia Building Authority.

The fund-raising effort was ambitious; a wagon train crossed the state, visiting each of the state’s former capitals. In June 1979, after a journey of almost six weeks, the wagon train pulled up to the city limits of Dahlonega, where Governor George Busbee boarded the lead wagon and drove it for the final few miles. Before the end of the year, enough gold for the dome had been collected.

By 1981 the total regilding of the capitol dome was complete. Gold leaf is very thin and vulnerable to heat, wind, and rain damage, so by the 1990s flaking was again occurring on the dome. Today, rather than waiting until the damage is visible from the ground, the Georgia Building Authority now repairs the damage as it occurs.

Only ten other states have capitol domes covered with gold leaf: Colorado, Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. Of these, the gilded domes of Iowa and Georgia are the largest.

Capitol Complex

At the time of its dedication, the Georgia capitol was only half filled with occupants. Twenty years later, however, the state government had grown to the point that the adjutant general declared the need for a capitol annex.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Works Progress Administration, created by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program, constructed several new buildings for use by state agencies. In 1951 the legislature created the State Office Building Authority (later the Georgia Building Authority) to borrow money for the construction of new state office buildings. Today, most agencies of Georgia’s state government have their headquarters in an area known as the “state capitol complex,” which consists of all or parts of ten square blocks surrounding the state capitol.

The latest addition to the complex is the twenty-story Twin Towers Office Building, officially designated the James H. “Sloppy” Floyd Veterans Memorial Building. Constructed in the early 1980s, Twin Towers is the first office building in the complex to rise above the capitol in height. Its high-rise style was part of a 1974 capitol complex master plan for future state office buildings. Since the completion of Twin Towers, however, no new state office buildings have been constructed in the capitol complex.

Courtesy of Georgia Info, Digital Library of Georgia.

During the late 1980s, the old Health Building across the street from the state capitol was converted into the Legislative Office Building (later the Paul D. Coverdell Legislative Office Building), and in the 1990s a new state parking deck was built to the east of Twin Towers. In 2003 the marble-covered state archives building in the state capitol complex was closed, and the facility was relocated to Morrow.