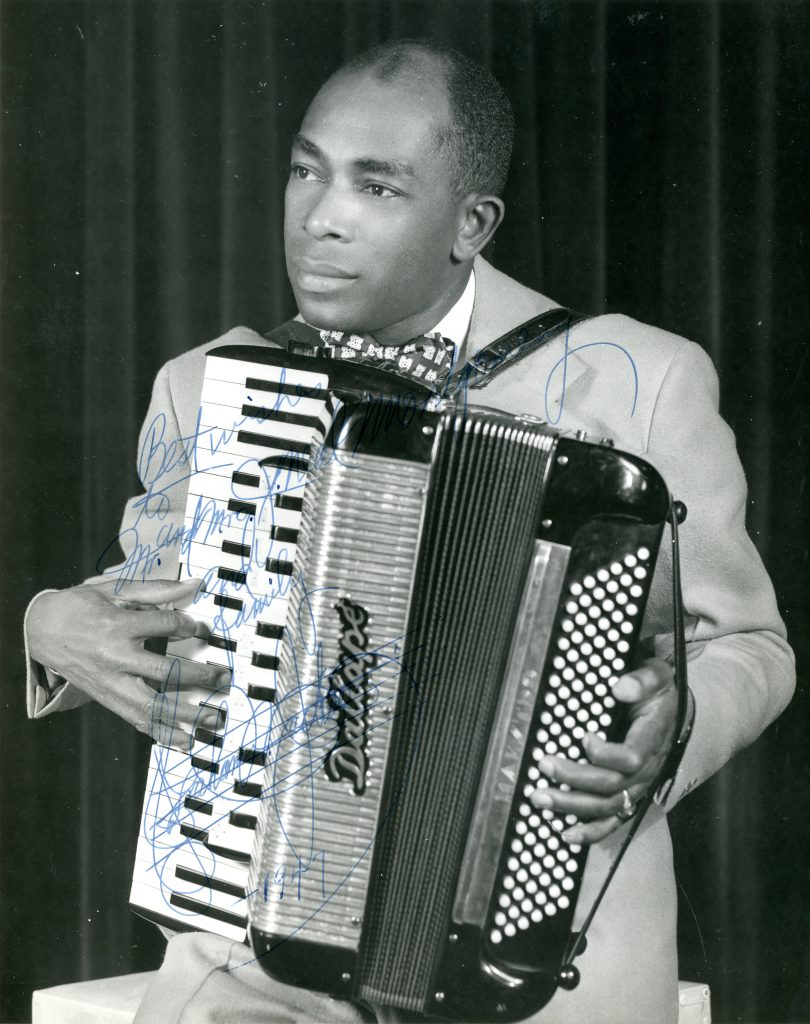

Graham Washington Jackson Sr. was a musician and band leader best known for his personal connection to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He performed for six presidents and was affectionately known as “The Ambassador of Good Will” during his lengthy career.

Jackson was born in Portsmouth, Virginia on February 22, 1903. He was raised in poverty by his aunt after his father lost his arm in a hunting accident and his mother was committed to a mental hospital. As a child he played hymns on the piano before he could write, and as a teenager he composed his own music.

Jackson moved to Atlanta, Georgia to attend Morehouse College in 1924. Within months he formed a jazz band called the Seminole Syncopators. Their first record, “Blue Grass Blues / Sailing on Lake Pontchartrain” was recorded in New York and Atlanta in 1924. The group performed on WSB radio in August that year, making them among the first African American artists to perform on the station. Jackson was also the house pianist at Bailey’s 81 Theatre, where he performed with artists such as Count Basie and Bessie Smith.

In 1928 Jackson became Music Director at Booker T. Washington High School, the only public African American High School in Atlanta. He trained a generation of students by conducting the orchestra, glee club, and band. He also started a long tenure as organist at First Congregational Church and performed regularly on the Mighty Mo organ at the Fox Theatre.

Jackson developed relationships with wealthy white patrons who regularly hired him and his orchestra for events, and it was through these connections that he met Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the years that followed, Jackson would perform for Roosevelt over twenty-four times, often at the Little White House in Warm Springs and occasionally in Washington.

Jackson and his Plantation Revue group played alongside then-pastor Martin Luther King Sr.’s Ebenezer Baptist Church choir at the opening festivities of the 1939 premiere of Gone with the Wind, a major event in Atlanta. Accompanying the musicians were performers from several African American churches including a ten-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. The decision to support the event aroused controversy in some quarters. African American leader John Wesley Dobbs, for one, was disgusted by the slave attire worn by the Black musicians, considering their participation an unconscionable affront to racial pride.

Segregationist policies limited the service roles available to African Americans during World War II (1941-45), but President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to pressure from the Black press by ordering the Navy to enlist African American musicians as naval bands. Jackson volunteered to serve and was quickly promoted to Chief Petty Officer. He was tasked with recruiting African Americans for naval service and went on to raise over three million dollars in War Bond sales, receiving six commendations for his bond work.

After Roosevelt died at Warm Springs in April 1945, Jackson reflected on his final performance for the President, saying, “He looked so broken. I was alone with him one whole evening on that visit. ‘Graham’, he said, ‘I am so tired. Play to me and let me rest.’” When Roosevelt’s body was taken from Warm Springs, Jackson performed one of the president’s favorite songs, “Going Home,” on the accordion. Life magazine photographer Ed Clark snapped an iconic photo of Jackson weeping while playing that came to epitomize the nation’s grief. Jackson later remodeled his home in Atlanta to be a replica of the Little White House and successfully petitioned the city council to rename the street White House Drive.

Jackson continued his musical career throughout the 1950s, appearing on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town and the Today Show. He also appeared in Coca-Cola advertisements marketed to African American customers. Jackson produced two additional record albums, the first a collection of traditional African American music arranged and directed by Jackson titled Spirituals, and the second a solo organ album titled Solid Jackson.

The centennial of the Civil War and white resistance toward integration brought nostalgia for the antebellum era and the Confederacy. During this period, Jackson held a musical residency at Dixieland, one of four Johnny Reb’s restaurants around Atlanta that memorialized the Old South. Like other commercial memorials to the Confederacy, Johnny Reb’s restaurants elicited criticism from Black media and political leaders; in 1962 the NAACP picketed the chain’s downtown location in protest of its segregationist policies. In 1967 Jackson moved to another neo-Confederate themed restaurant, Pittypat’s Porch. Jackson also recorded Civil War-themed albums in conjunction with his restaurant appearances.

In 1969 Jackson became the first African American appointed to Georgia’s State Board of Corrections when Governor Lester Maddox, an ardent segregationist, selected him for the post. Skeptics considered Jackson an “Uncle Tom” appointment who failed to represent meaningful reform and lacked requisite expertise in criminal justice. Jackson acknowledged that Maddox had selected him because he was Black, saying that the governor was a “very fine man” who “wants to help the whole system and give it a new approach.” When asked directly how he could accept an appointment by a man opposed to civil rights, Jackson replied, “I’m a musician, not a politician… He has treated me very fine.”

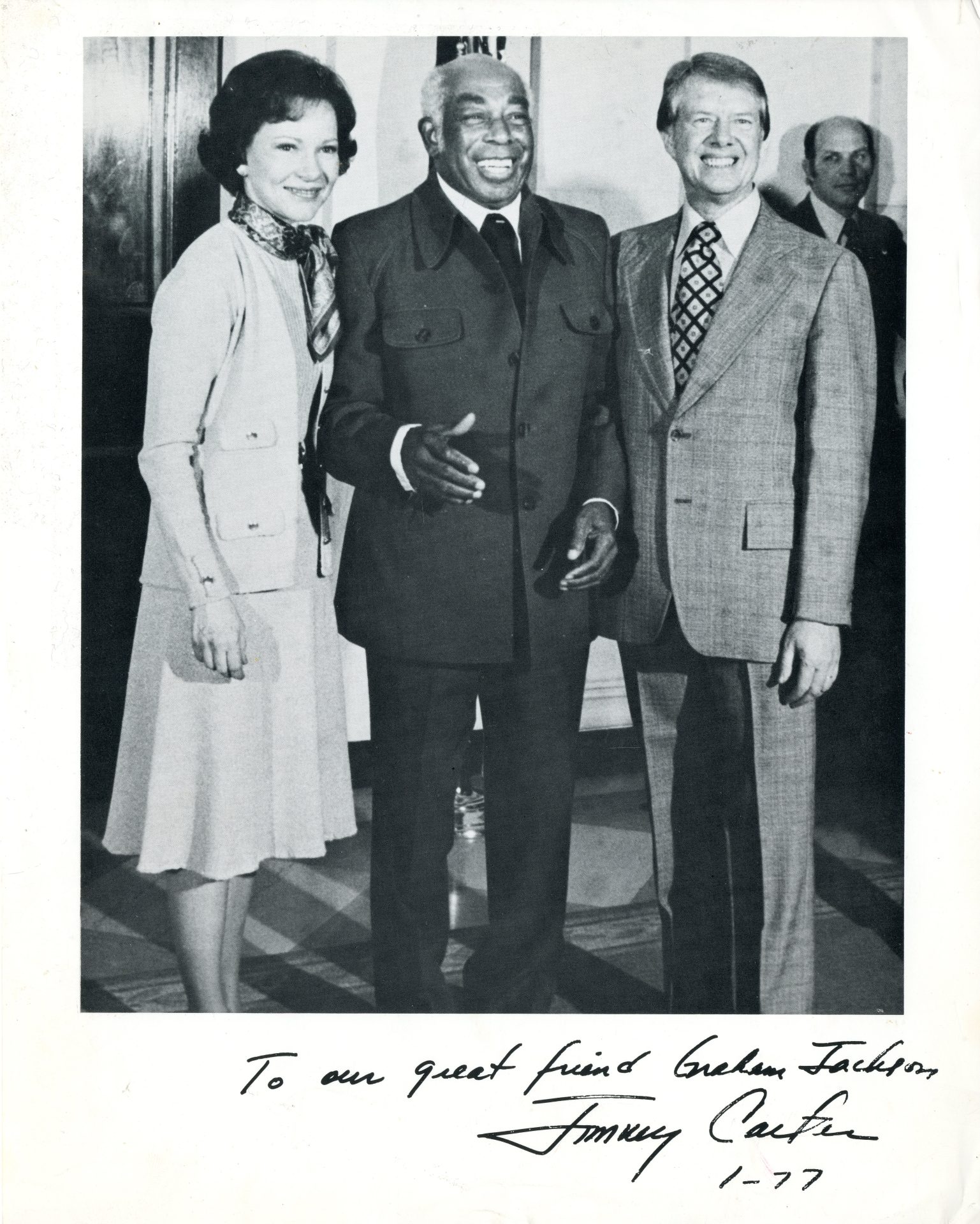

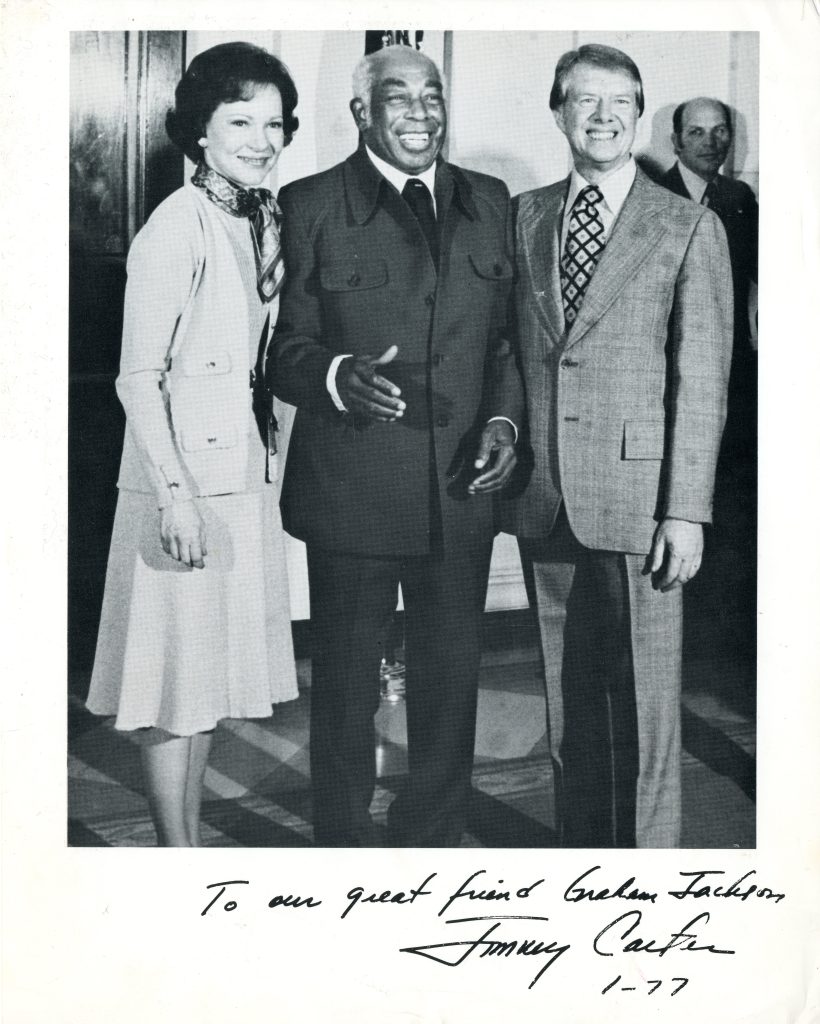

Jackson proved popular with Maddox’s successor as well. As governor, Jimmy Carter named Jackson the official musician of the State of Georgia. In 1976, after winning the Democratic nomination for president, Carter invited Jackson to perform at his campaign’s opening event, held at Warm Springs. And after taking up residence in Washington, Carter welcomed a delegation of Georgians to the White House, where Jackson was again the featured performer.

Jackson died on January 15, 1983, leaving behind his wife Helen, and sons Graham Jr. and Gerald Jackson.