At the time of the Civil War (1861-65), Atlanta boasted a population of almost 10,000 (one-fifth of whom were enslaved), a substantial manufacturing and mercantile base, and four major railroads connecting the city with all points of the South. Although it was neither Georgia’s capital nor the largest city in the state, Atlanta was energetic and thriving, and its strategic importance to the Confederate war effort grew as the conflict continued.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Early War

After the outbreak of war in spring 1861, Atlantans volunteered and formed the bulk of the twelve companies of infantry from Georgia. Casualties soon occurred. The city’s two main newspapers, the Intelligencer and the Southern Confederacy, honored nearly a dozen Atlantans who had been killed at the First Battle of Manassas, Virginia, on July 21. Soldiers’ deaths left some families destitute; fund-raising groups formed to aid them, and physicians offered free care.

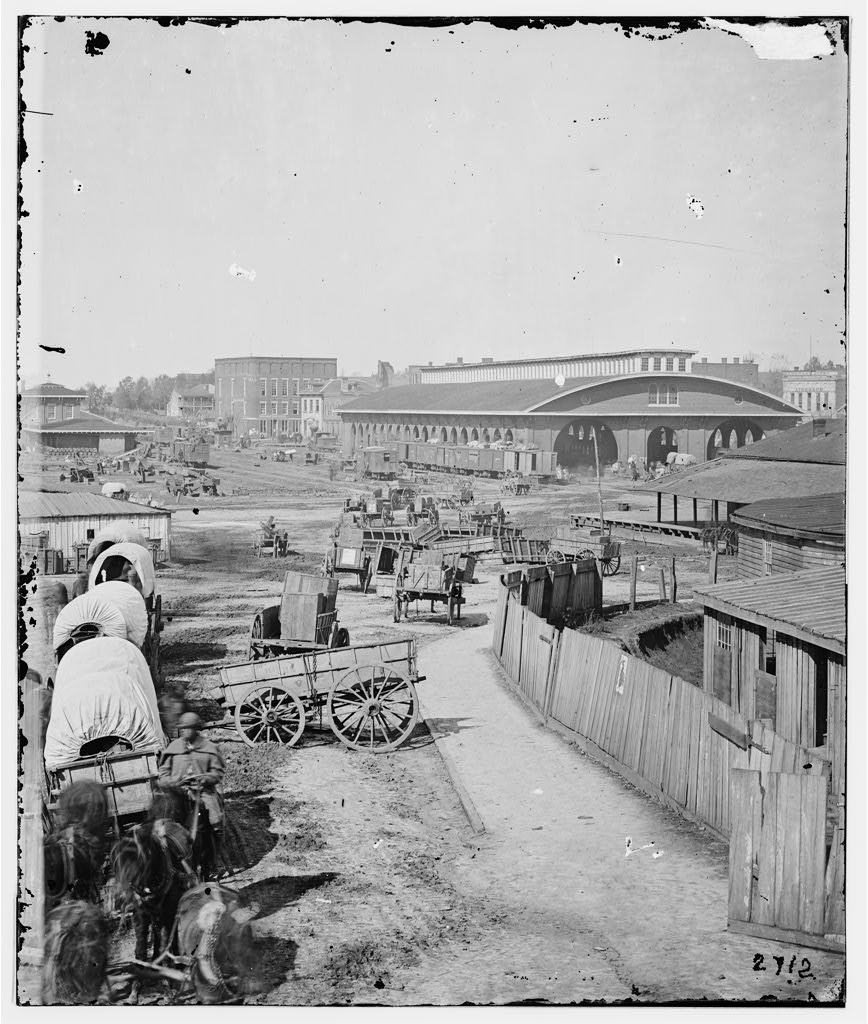

With the Confederate loss of middle Tennessee in early 1862, Atlanta became the South’s military medical center. The Atlanta Medical College (later Emory University School of Medicine), which had already suspended classes, became a hospital, as did hotels and municipal buildings. Construction of a big hospital complex on the city fairgrounds eventually relieved the crowding of sick and wounded soldiers downtown. The railroad passenger depot in the center of town served as a busy receiving and distributing point for Southern servicemen. A convalescent camp was established in the northwest suburbs, near the home of Ephraim Ponder. The city cemetery, then twenty-five acres (today known as Oakland Cemetery and much larger), also had to be expanded; some 632 soldiers were buried during 1862 alone.

Advances of Union forces in Tennessee and Mississippi made Atlanta a city of refugees. Its population was estimated at 17,000 in mid-1862 and 20,000 a year later. Hotels and boardinghouses were overwhelmed as newcomers took over vacant lots and train cars. So many strangers milled about that the city council put up Atlanta’s first street signs in May 1863.

Industrial Center

As a key railroad hub, Atlanta became an important military supply center. Commissary, quartermaster, and ordnance stores were warehoused throughout the town. More important were Atlanta’s manufacturing facilities. Schofield and Markham’s Atlanta Rolling Mill was one of only two in the Souththat could produce rails. The mill also turned out plating for such Confederate ironclad gunboats as the Tennessee. Smaller manufactories were more numerous and just as important, such as James L. Dunning’s Atlanta Machine Works. After Dunning, who was a member of the city’s small, secret circle of Union loyalists, refused to accept Confederate weapons contracts, the government took over the plant, which produced artillery shells and small arms. Other shops under government contract turned out swords, buttons, buckles, cartridge boxes, saddles, bridles, and other items.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs division

The government also set up its own operations, such as the arsenal built at the racetrack outside the city’s western limits; it produced percussion caps and artillery and small-arms ammunition, probably as many as 75,000 rounds per day by August 1862. In 1863-64 the Atlanta Arsenal employed nearly 5,500 men and women. In spring 1863 the Confederacy’s Quartermaster Department had some 3,000 women in the city working as seamstresses and turning out thousands of wool jackets, pants, and cotton shirts. A government shoe factory produced 500 pairs a day, when leather supplies permitted. Bakeries and meatpacking plants made Atlanta a major army commissary as well.

Defending Atlanta

All these valuable shops and warehouses made Atlantans suspicious of spies and secret Union incendiaries in their midst. Martial law was declared for only a month in August 1862, but citizens suspected of having Union sympathies were always threatened with arrest. In the spring of 1863, when Union cavalry raided close to Rome (sixty miles northwest of Atlanta), Atlanta mayor James M. Calhoun and the city council called upon all able men to form volunteer militia companies. Policemen, firemen, railroaders, and ordnance workers all formed companies, ready for the next Union approach.

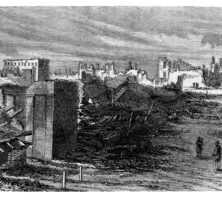

The city fathers resolved on May 22, 1863, that longtime Atlantan Lemuel P. Grant, captain of the Confederacy’s Engineer Bureau and senior engineer with headquarters in the city, should survey along the Chattahoochee River for defensive earthworks to prevent enemy crossings of the river. Two months later the War Department Engineer Bureau in Richmond, Virginia, ordered further protection for Atlanta: preparation for a “proper system of defense,” presumably a fortified perimeter around the city. That August, Captain Grant proposed his line of rifle pits and artillery forts, ten miles in circumference, averaging a mile outside the city. Thus after the fall of Chattanooga, Tennessee, in September 1863 and the Confederate army’s retreat into north Georgia, but well before the onset of Union general William T. Sherman’s campaign against Atlanta in the spring of 1864, the city had begun to ready itself.

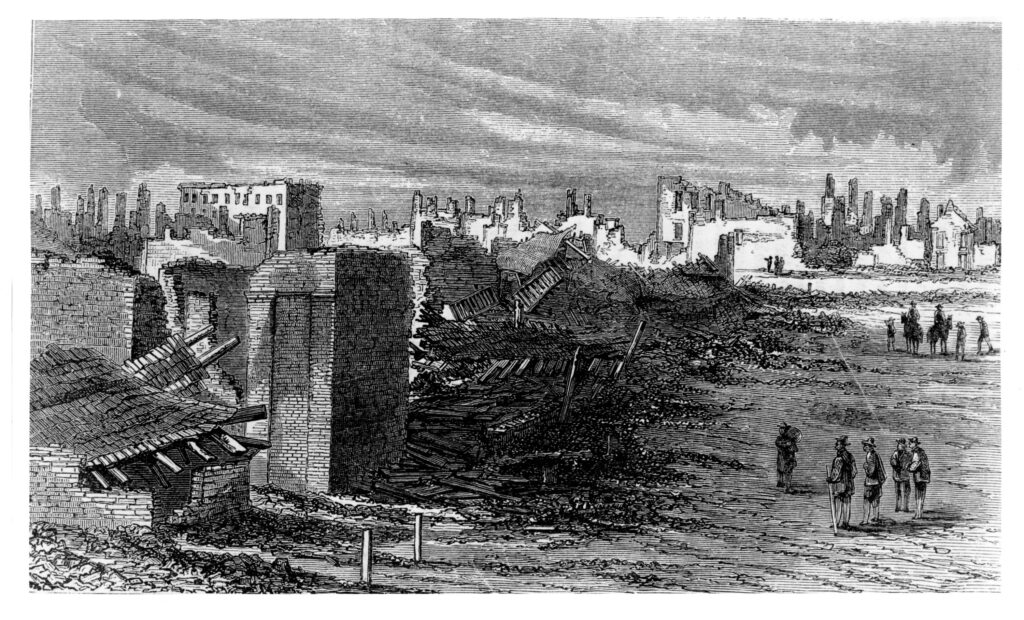

From Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign, by G. N. Barnard

Local Response to Sherman’s Attack

The approach of Sherman’s armies threw Atlantans into alarm. Newspaper editors urged calmness and chastised gloomy “croakers” who began to predict the city’s fall. Increasing numbers of wounded soldiers arrived by train as the battles moved closer; the fall of Rome and other nearby towns poured more refugees into the city. Atlantans heard their first distant thud of cannon fire on May 25, 1864, when General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate army held Sherman’s forces near Dallas, in Paulding County. After the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain on June 27, a panic gripped many townspeople, who packed their families and belongings and fled. Even Mayor Calhoun sent his wife and two children away. Confederate officials began moving arsenal machinery to Macon and Augusta. On July 5 General Johnston ordered the military hospitals to pack up and leave. After Union troops got across the Chattahoochee River near Roswell, Johnston withdrew his army across the river in the night of July 9-10. The news heightened the public panic. Civilians vied with ordnance and medical officers for train and wagon space.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

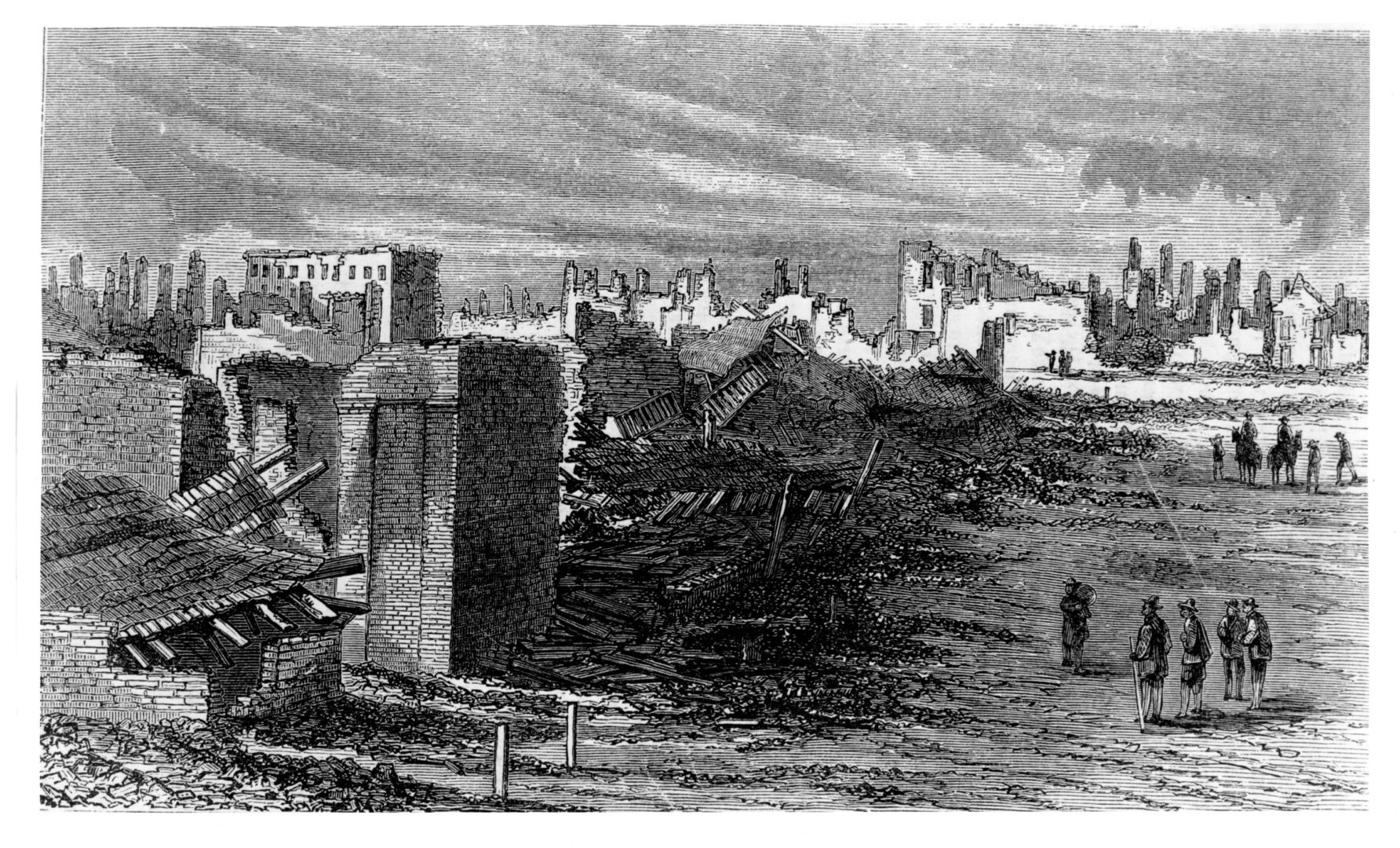

The Confederate government’s replacement of Johnston with General John Bell Hood did little to bring calm. On July 20 the jarring sounds of battle at Peachtree Creek mixed with that of the first Union shells falling into the city—Sherman had ordered a bombardment of the downtown area to pressure Hood into evacuation. The thirty-six-day shelling drove more civilians to leave. Judging from newspaper reports, Sherman’s artillery fire killed perhaps only a score of civilians but probably wounded hundreds more (medical records are nonexistent). The daily cannon fire intensified until August 9, when 3,000 to 5,000 exploding shells fell downtown, damaging and destroying countless buildings. Many townspeople, especially the poor, could not leave. Some simply chose to stay, seeking shelter in basements or specially dug “bombproofs.” With stores and commerce closed, they fared on garden produce and rations distributed by the army.

From Harper's New Monthly Magazine, v.31 (June-Nov 1865)

From a population of about 22,000 in the spring of 1864, probably 3,000 civilians remained in the city when the Confederate army was forced out of Atlanta on September 1. Days later, Sherman ordered almost all noncombatants to leave town. With their exodus, Atlanta’s significance as a Confederate military and industrial hub dissolved.