Hall Johnson was a highly regarded African American choral director, composer, arranger, and violinist who dedicated his career to preserving the integrity of the Black spiritual as it had been performed during the era of slavery.

His Hall Johnson Choir, the first professional group of its kind, enjoyed a successful concert and recording career for more than three decades in the United States and abroad. During his professional life Johnson coached hundreds of distinguished musicians, including the famous opera singer Marian Anderson. Virtually every Black singer of note has performed Johnson’s solo compositions and arrangements.

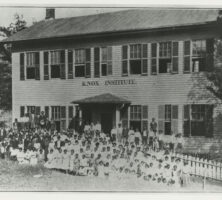

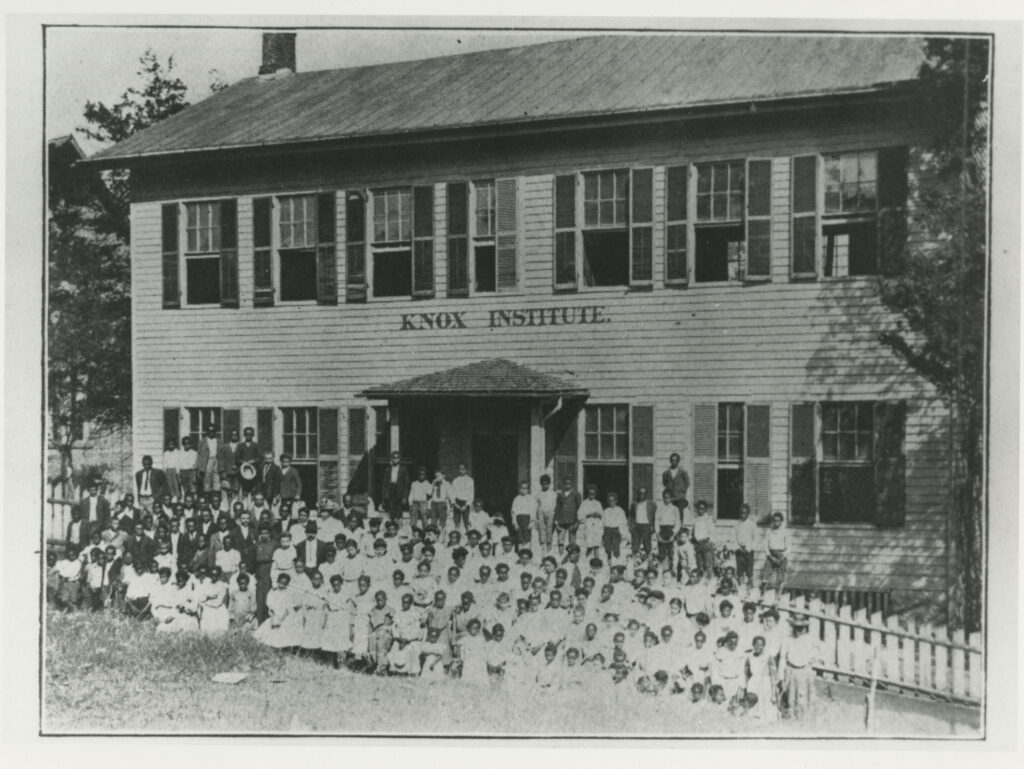

Francis Hall Johnson was born in Athens on March 12, 1888, to Alice Virginia Sansom and William Decker Johnson, an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) bishop and native of Sumter County. Bishop Johnson also founded a school for African Americans in Webster County. He showed musical talent at an early age and studied piano with his older sister, Mary Elizabeth. As a child he heard Black spirituals sung by his mother as well as his grandmother, Mary Hall Jones, both of whom had been enslaved. By the time he was eight, Johnson was already writing down songs he heard. Inspired by hearing a violin recital given by Joseph Henry Douglass, grandson of Frederick Douglass, Johnson wanted to play the violin and was given one at age fourteen. Determined to master the instrument, he taught himself to play using a self-instruction manual. After graduating from the Knox Institute in Athens in 1903, Johnson continued his education first at Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), then at Allen University in Columbia, South Carolina, and finally at the University of Pennsylvania, where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in music in 1910. In 1912 Johnson married a fellow Athenian, Celeste Corpening.

By 1914 Johnson and his wife had settled in New York City, where he became a member of the dance orchestra of Vernon and Irene Castle. Tireless in advancing his career, Johnson also taught violin at his own studio, and in 1918 he joined Will Marion Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra, which toured the country performing African American folk music, blues, syncopated songs, and standard popular tunes. In 1921 he was a member of the orchestra of the Broadway production of Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along, and he also participated in that show’s sequel, Runnin’ Wild, which introduced the Charleston dance to Broadway.

In 1923 Johnson began to perform as the violist in the Negro String Quartet, a group that won critical acclaim for its interpretations of the standard European classical repertoire and also introduced American concert audiences to works by contemporary Black composers. Towering over his fellow performers, Johnson became known as “the tallest viola player in New York.”

Sitting in orchestra pits and hearing performances of Black spirituals presented in essentially white barbershop harmonies, Johnson sought to present the rich legacy of African Americans in a more authentic fashion. In the fall of 1925 he formed a choir of eight voices. The singer Bob Caver persuaded the choir, first called the Harlem Jubilee Singers, to take the name of its founder and director. At first the small group of eight members sang in local churches and performed on a few broadcasts. They made their formal New York City debut in March 1926 and were soon acclaimed as one of the most impressive musical groups of the Harlem Renaissance.

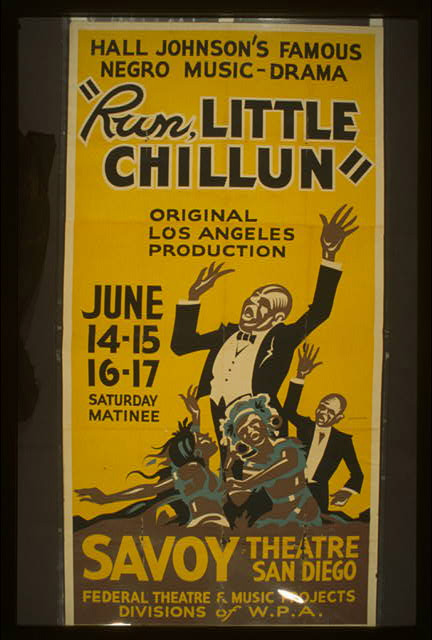

Within a few years of its debut, the Hall Johnson Choir was performing to enthusiastic audiences at various prestigious New York City venues. National recognition came in March 1930, when Johnson’s choir performed under his direction (and using his arrangements) in Marc Connelly’s Green Pastures. In 1933, despite the economic depression, Johnson’s folk opera Run Little Chillun enjoyed a Broadway run of four months.

In 1935 Johnson took his choir to California to participate in the film version of Green Pastures (1936). Johnson’s group remained in California, appearing in many films, including Hearts Divided (1936), Banjo on My Knee (1936), Lost Horizon (1937), Dumbo (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Cabin in the Sky (1943). Extremely active in the Hollywood film studios, in 1938 Johnson recruited local African American talent to found another ensemble, the Festival Choir of Los Angeles.

In 1946 Johnson returned to New York, where he organized the Festival Negro Choir of New York and conducted the premiere performance of his Easter cantata, The Son of Man. In 1951 the Hall Johnson Choir was chosen by the U.S. Department of State to represent America at the International Festival of Fine Arts, held in West Berlin, Germany.

A lifelong student and champion of the Black spiritual, Johnson dedicated his long career as a choir director to preserving and interpreting the rich legacy of African American music that developed under slavery. In 1965 Johnson published an essay, “Notes on the Negro Spiritual,” in which he explained the significance of this Black American art form. He coached several generations of singers and conductors, including Marian Anderson, Harry Belafonte, Leonard De Paur, and Shirley Verrett. In 1970 New York City honored Johnson with its Handel Award.

Johnson died in an apartment fire on April 30, 1970, possibly a result of his having fallen asleep with a lighted cigarette. One writer has pointed out that, ironically, a number of Johnson’s compositions, including his 1959 operetta Fi-yer! used fire as their subject matter.

In 1975 Johnson was posthumously elected to the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. In 1976 he was honored by his hometown of Athens with a plaque in city hall, and in 2020 he was among the first ten musicians inducted into the Athens Music Walk of Fame. A sidewalk marker near the historic Morton Theatre now honors his contributions to the city’s musical legacy.