The Reverend Henry Hugh Proctor was the first African American pastor of First Congregational Church in Atlanta, serving from 1894 until 1920. His dynamic leadership and efforts to improve race relations, especially after the 1906 Atlanta race massacre, made him a key figure in the Social Gospel movement and a significant precursor of the civil rights movement.

Early Life

Proctor was born in rural Tennessee on December 8, 1868, to formerly enslaved parents Hannah Murray and Richard Proctor, a carpenter. He had four older siblings, all born before the Civil War (1861-65). The first school he attended, where the term was only the three summer months, doubled as a church. Children and parents worked in the fields. His father even fashioned a small plow for the young Henry. The family at one point lived twelve miles from Pulaski, where six Confederate veterans had founded the Ku Klux Klan in 1866.

When Proctor was around twelve years old, the family moved to Fayetteville, Tennessee—population 2,104—in search of better schools. There Proctor completed the common school course, taught briefly at a small rural school, and then returned to the city school to serve as principal.

Higher Education

In 1884 Proctor scraped together enough money to attend the spring term at Central Tennessee College in Nashville. He transferred the following autumn to Nashville’s Fisk College (later Fisk University). Founded in 1866 by the American Missionary Association (AMA), Fisk was one of numerous AMA-backed institutions devoted to the education of freedmen and freedwomen.

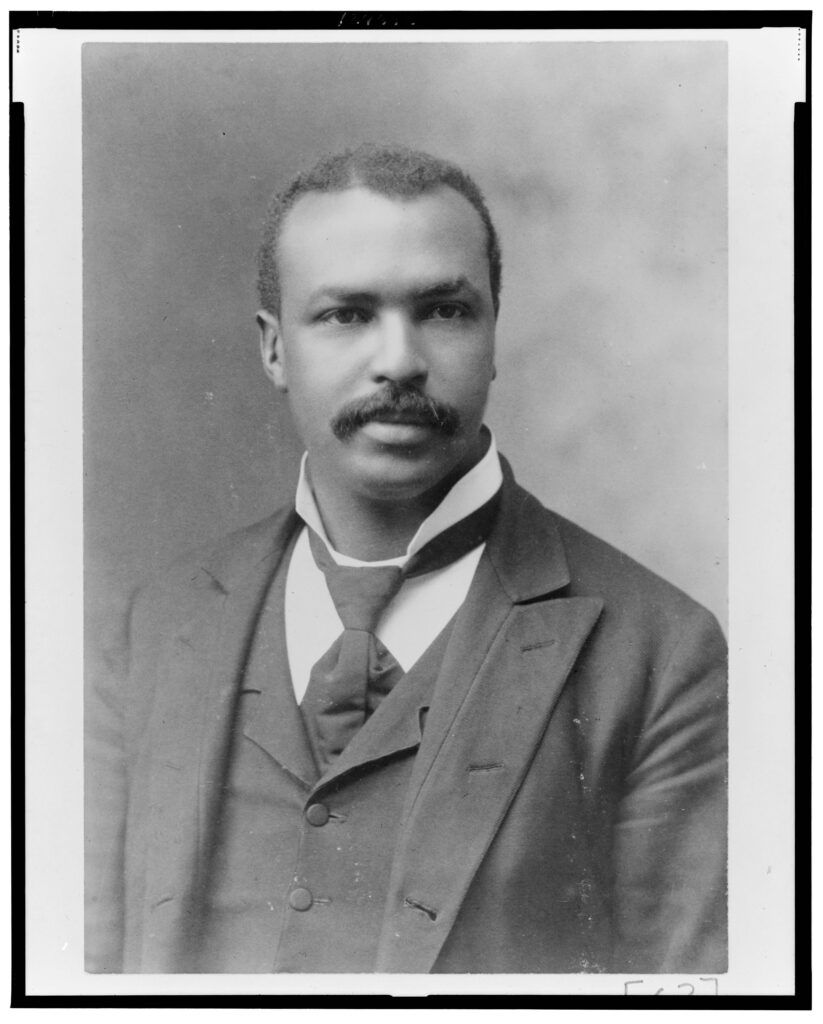

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Proctor attended Fisk for seven years, working to pay for his expenses. His time at the college shaped his future significantly. Music was an important part of life at Fisk, an experience that influenced Proctor well beyond graduation. Among his friends was fellow student W. E. B. Du Bois, who later became a prominent educator and leader. After graduating from Fisk, Proctor enrolled at Yale Divinity School in New Haven, Connecticut.

The academic offerings at Yale—Greek and Hebrew, philosophy, systematic theology, elocution, sacred music, benevolent work—dazzled Proctor. He and three other Black students formed a quartet, singing at local churches to earn tuition money. Proctor’s passion for music led him to write his thesis on the theology of southern slave songs. Meticulously, he parsed phrases from those spirituals, asserting their grounding in orthodox Christianity and noting that the songs are free from a thirst for revenge. He received his Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1894.

First Congregational Church

After graduating from Yale, Proctor accepted a call to First Congregational Church in Atlanta. His wife, Adeline L. Davis, accompanied him. The couple, who had married in 1893, later became the parents of six children.

First Church, as it was called, had been organized in 1867 as an outgrowth of the Storrs School, founded in Atlanta after the Civil War by the AMA for the education of African American children. The church’s membership included many leaders in the Black community. It was there that Proctor became prominent in the Social Gospel movement of the Congregational Church. Adherents of this movement supported social reform and were involved in such issues as civil rights, workers’ rights, and woman suffrage.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Proctor increased membership significantly in First Church to 1,000. His zeal reached far beyond his own church—to the city and the nation. Clark University (later Clark Atlanta University) recognized his contributions to the community in 1904 by granting him an honorary doctorate. Two years later, his leadership was integral in helping the city recover from the devastation of the Atlanta race massacre. With white lawyer Charles T. Hopkins, Proctor formed the Interracial Committee of Atlanta, composed of twenty Black men and twenty white men, to promote interracial cooperation in the city.

The massacre ignited a new fervor in Proctor. He had a vision of a church open and active, serving its people in every aspect of their lives. He began fund-raising on an ambitious scale, first targeting his own parishioners, then the local white community, and then—with educator Booker T. Washington’s help—sympathetic citizens all over the country. The church built an expansive new complex with facilities that supported a range of ministries, including Sunday school classrooms, a library, a gymnasium, a 1,000-seat auditorium, a residence for young working women, and a “trouble bureau,” which served as a “clinic for all sorts of ills.” One of the humblest installations in the new complex had a striking social significance during this era of segregation: a public water fountain from which anyone, Black or white, could take a drink of water.

Proctor believed in ministering to the whole person—body, mind, and spirit. The activities of his church attracted national attention. In November 1914 famed advertising mogul and author Bruce Barton, after visiting First Church, published an article in The Congregationalist and Christian World entitled “The Church That Saved a City.” When U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt visited in 1910, a year after leaving the White House, Proctor gave him a tour of the church complex. He showed the president a portrait of himself, displayed beneath a big stick, a visual reference to Roosevelt’s famous comment, “Speak softly, and carry a big stick.” Proctor reported that the president “chuckled delightedly.”

Music remained integral to Proctor’s life. In 1910 he organized, with the Atlanta Colored Music Festival Association, a classical music concert featuring Black performers, including renowned baritone and composer Harry T. Burleigh, who had performed extensively in Europe. The concerts continued annually, attracting both Black and white audiences, until 1918. They were revived as the Atlanta Music Festival in 2001 by the Reverend Dwight Andrews of First Congregational Church and Steve Darsey of Glenn Memorial United Methodist Church at Emory University.

Travels

During the decades of his ministry in Atlanta, Proctor traveled extensively in the United States and Europe. When the new First Church facilities were completed in 1908, Proctor’s parishioners presented him with $1,000 for a trip to the Holy Land. Refused the opportunity to travel with U.S. touring groups because of his color, Proctor journeyed on his own through Greece, Egypt, the Middle East, Italy, and Germany. He found a different racial attitude abroad, writing, “As the skyline of New York faded out, the color line faded with it.”

After the end of World War I (1917-18), the U.S. War Department asked Proctor to visit the Black troops who remained in Europe. In March 1919 he arrived in France and for the next three months traveled around the country, delivering motivational sermons to around 100,000 soldiers.

Proctor left First Church in 1920 to head Nazarene Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York. In so doing, he found himself on the front lines of what historians would later identify as the first wave of the Great Migration, when more than a million African Americans moved from the rural South to find jobs in the urban North between 1910 and 1930.

Proctor died unexpectedly on May 12, 1933, and was buried in Atlanta. Du Bois published a memorial summing his friend’s achievements in the pages of The Crisis, the journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People:

One of the first men I met, when I came to Fisk in 1887 was Henry Hugh Proctor, a long lanky youth. . . . He grew into a strong and forceful man and dying before his day, left a mark on the world. . . . His great work was the community church in Atlanta, perhaps the first and certainly one of the most successful in Colored America. . . . But neither the time of his coming nor the character of this community was suited to his plans. . . . Yet he was ever at the edge of a new great triumph.