Howard Swanson was a highly regarded African American composer of classical music whose works have been performed by major orchestras and leading concert singers. Overcoming racism and economic challenges, his life reflected his heartfelt statement, “The only thing I live for is my music.”

Swanson was born in Atlanta on August 18, 1907, to Mamie Thomas and Howard Swanson. Swanson’s mother had taught school before her marriage and was active in Atlanta cultural life. She determined that not only Howard but also her other three children would receive musical instruction. As a boy Swanson possessed a beautiful soprano voice, and he often sang duets with his mother at their own church and other churches in the community. During summers he lived on his father’s farm outside Atlanta, where he was stirred by the rousing hymns of the church congregation using the “sol-fa” or shape-note system.

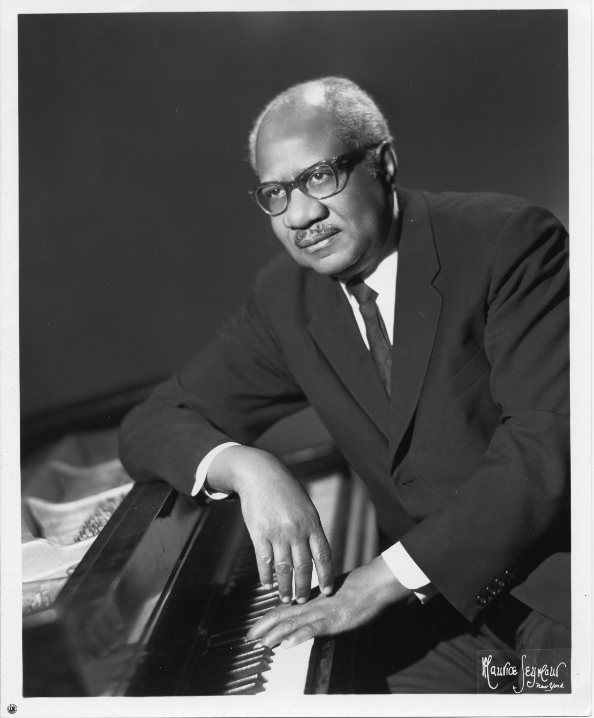

Courtesy of the Center for Black Music, Columbia College, Chicago. Photograph by Maurice Seymour, New York

In 1916, seeking economic opportunity, the Swanson family left Atlanta for Cleveland, Ohio. Two years later, Swanson began to study piano. In 1925 he graduated from Cleveland’s Glenville High School. That same year, his father died, and the Swanson family was thrown into a financial crisis. As the oldest son, Swanson was forced to find a job in order to support his mother and siblings. For a time he worked at the New York Central Railroad’s roundhouse, where his father had been employed. Soon he found employment with the U.S. Postal Service, where he worked for more than a decade.

Determined to expand his musical horizons, in 1930 Swanson began to study piano at the Cleveland Institute of Music. Several of his teachers became aware of his musical talents and persuaded him to work at night so that he could take a full course of study during the day.

The burden of maintaining a full-time job made it impossible for Swanson to devote the time required to become a piano virtuoso. Instead, he aspired to become a composer. In Cleveland Swanson studied composition with Herbert Elwell, a composer who had studied in Paris, France, with the noted teacher Nadia Boulanger, whose other American students included composer Aaron Copland. In 1938, having been awarded a coveted Rosenwald Fellowship, Swanson traveled to Paris to study with Boulanger.

Following the German occupation of Paris in June 1940, the young musician was forced to return to the United States in 1941, on the eve of World War II (1941-45). Several lean years followed, with Swanson working as a file clerk for the Internal Revenue Service. Regular employment left him with little time or energy for composing, but determined to create a major work, he quit his job in 1943 and composed his first symphony.

The year 1950 proved to be crucial in Swanson’s career. On January 15,1950, the opera singer Marian Anderson performed his 1942 setting of a Langston Hughes poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” at New York’s Carnegie Hall. Anderson made this song part of her repertoire and performed it during her farewell American tour in 1964-65. In the summer of 1950 the noted conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos heard several of Swanson’s songs performed at a concert and asked Swanson if he might have an orchestral work to present at one of his future concerts with the New York Philharmonic. Swanson’s reply was that he did indeed have such a work—his Symphony no. 2 (Short Symphony), composed in 1948.

On November 26, 1950, Mitropoulos gave the world premiere performance of this symphony with the New York Philharmonic. Audience response was enthusiastic, and the astute New York Herald Tribune critic (and composer) Virgil Thomson praised the Neoclassical symphony for its “highly personal” nature and for speaking “clearly, warmly, modestly and at the same time with authority.” Other critics agreed with Thomson, awarding the Short Symphony the New York Music Critics Circle award as the most interesting composition of the season.

In 1952 Swanson received a grant from the National Academy of Arts and Letters and a Guggenheim Fellowship. These two honors enabled him to return to Europe. He lived in Paris and for a time in Vienna, Austria, as well, from 1952 through 1966, when he returned to New York.

Best known for his art songs, most notably “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” and for the Short Symphony, Swanson composed a number of other distinguished works, including “The Cuckoo” Scherzo for Piano (1948); Suite for Cello and Piano (1949); “Night Music” (1950); “Music for Strings” (1952); Concerto for Orchestra (1957); and Symphony no. 3 (1969). In virtually all of his compositions, Swanson worked within the conventional forms of classical music, but he was able to infuse them with a personal style grounded in African American traditions. Swanson died in New York City on November 12, 1978, the same year in which Leontyne Price sang his “Night Song” at a performance at the White House.