From 1946 until his death in 1973, Jacob Rothschild served as rabbi for the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, Atlanta’s oldest and most prominent Jewish synagogue, also known as “the Temple.” Throughout his rabbinate, Rothschild forged close relationships with members of the city’s Christian clergy, helped to engineer Atlanta’s moderate political consensus, and distinguished himself as a charismatic spokesperson for civil rights.

Background

Jacob Mortimer Rothschild was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on August 4, 1911, to Lillian and Meyer Rothschild. He was raised in the Reform congregation Rodelph Shalom, where his own rabbi, Samuel Goldenson, used his position to oppose the exploitation of labor in Pittsburgh’s steel industry. Due in large part to Goldenson’s example, Rothschild decided to pursue a rabbinical career, enrolling in 1927 at the Hebrew Union College (later Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion) in Cincinnati, Ohio.

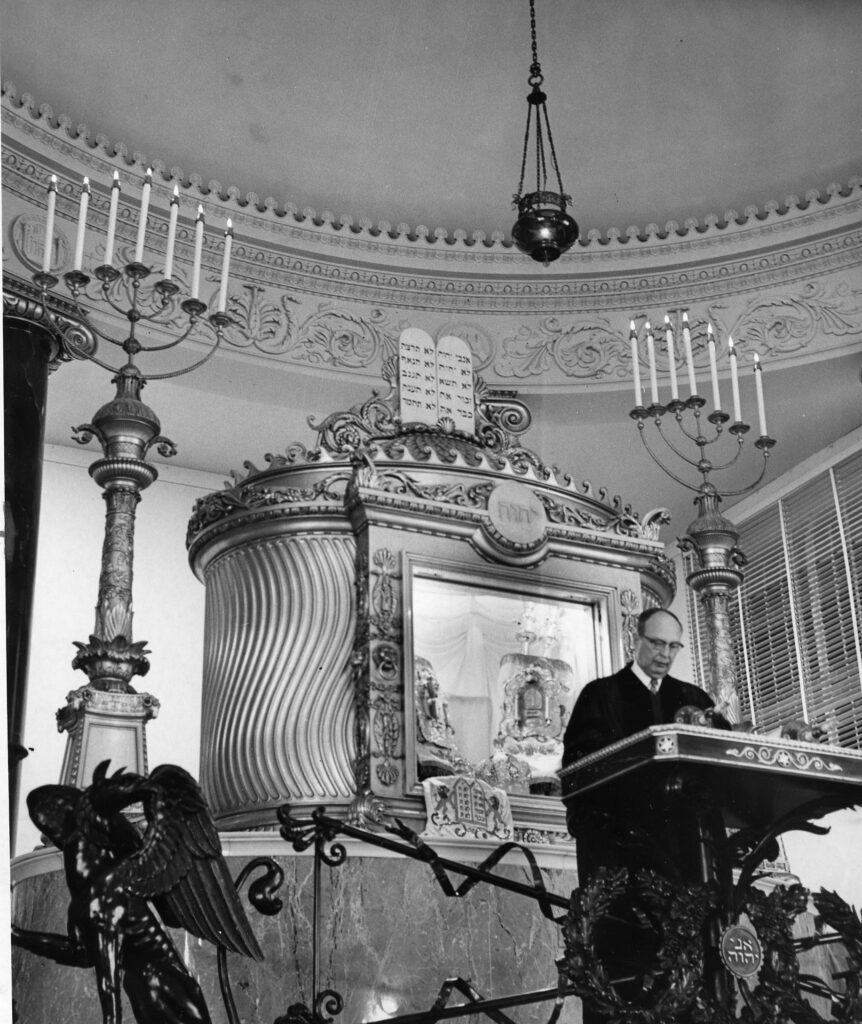

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

After completing his degree in 1936, Rothschild served brief stints at congregations in Davenport, Iowa, and in Pittsburgh before entering the army in March 1942. As a chaplain during World War II (1941-45), Rothschild was exposed to combat on the Pacific front, accompanying the American Division when it relieved marines at Guadalcanal in December 1942. A bout with malaria later forced him to return to the United States, where he remained for the duration of the war. After completing his military service in April 1946, Rothschild was offered the pulpit of Atlanta’s Hebrew Benevolent Congregation.

Civil Rights

Rothschild was disturbed by the depth of racial injustice he witnessed upon arriving in Atlanta and resolved to make civil rights a focal point of his rabbinical career. He first broached the topic in his 1947 Rosh Hashanah sermon but remained mindful of his status as an outsider and proceeded with some caution to avoid alienating supporters during his first few years in Atlanta. By 1954, however, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Brown v. Board of Education decision, which called for the desegregation of public schools, race relations had become a recurring theme in his sermons, and Temple members had grown accustomed to his support of civil rights.

At the same time, he reached out to members of the local Christian clergy and became active in civic affairs, joining the Atlanta Council on Human Relations, the Georgia Council of Human Relations, the Southern Regional Council, the Urban League, and the National Conference of Christians and Jews. In order to promote cooperation with his Christian colleagues, Rothschild established the Institute for the Christian Clergy, an annual daylong event hosted by the Temple each February. Black ministers were always welcome at the Temple’s interfaith events, and on other occasions Rothschild invited prominent Black leaders, such as Morehouse College president Benjamin Mays, to lead educational luncheons at the Temple, despite objections from some members of his congregation.

In 1957, when other southern cities were erupting in violent opposition to court-ordered school desegregation, eighty Atlanta ministers issued a statement calling for interracial negotiation, obedience to the law, and a peaceful resolution to the integration disputes that threatened Atlanta’s moderate reputation. The Ministers’ Manifesto, as the statement came to be known, marked an important turning point in Atlanta’s race relations. Although the Manifesto’s strong Christian language prevented Rothschild from signing it himself, the rabbi helped to draft and conceive the statement, and he endorsed it in an article that ran separately in both the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution and later appeared in the Congressional Record.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

While Rothschild’s activism won admiration from some quarters of the city, it earned contempt from others. When fifty sticks of dynamite exploded at the Temple on October 12, 1958, many observers concluded that the rabbi’s outspoken support of civil rights had made the synagogue a target for extremist violence. Because it was condemned by elected officials, members of the press, and the vast majority of ordinary citizens, however, the bombing resulted in a repudiation of extremism and a renewed commitment to racial moderation by members of official Atlanta.

Rather than withdraw from public life, Rothschild stepped up his activism following the bombing, speaking regularly in support of civil rights at public events throughout the city and region, and assuming the vice presidency of the Atlanta Council on Human Relations. Members of his congregation followed Rothschild’s lead, taking leadership positions in HOPE (Help Our Public Education) and OASIS (Organizations Assisting Schools in September), two influential organizations that helped ensure the peaceful integration of Atlanta’s public schools in 1961.

During this period Rothschild forged a close personal friendship with Martin Luther King Jr. After King received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, Rothschild helped to organize a city-sponsored banquet in King’s honor, for which also he served as master of ceremonies. Following King’s assassination in 1968, the combined clergy of Atlanta held a memorial service at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. Philip to pay their respects, and Rothschild was selected by his peers to deliver the eulogy.

In the years after King’s death, Rothschild’s opposition to the more militant measures adopted by younger Black activists cost him much of the support he once enjoyed from his African American counterparts in the civil rights movement. His diminished stature in the Black community notwithstanding, Rothschild continued to speak regularly and candidly about social justice and civil rights until he died, after suffering a heart attack, on December 31, 1973.