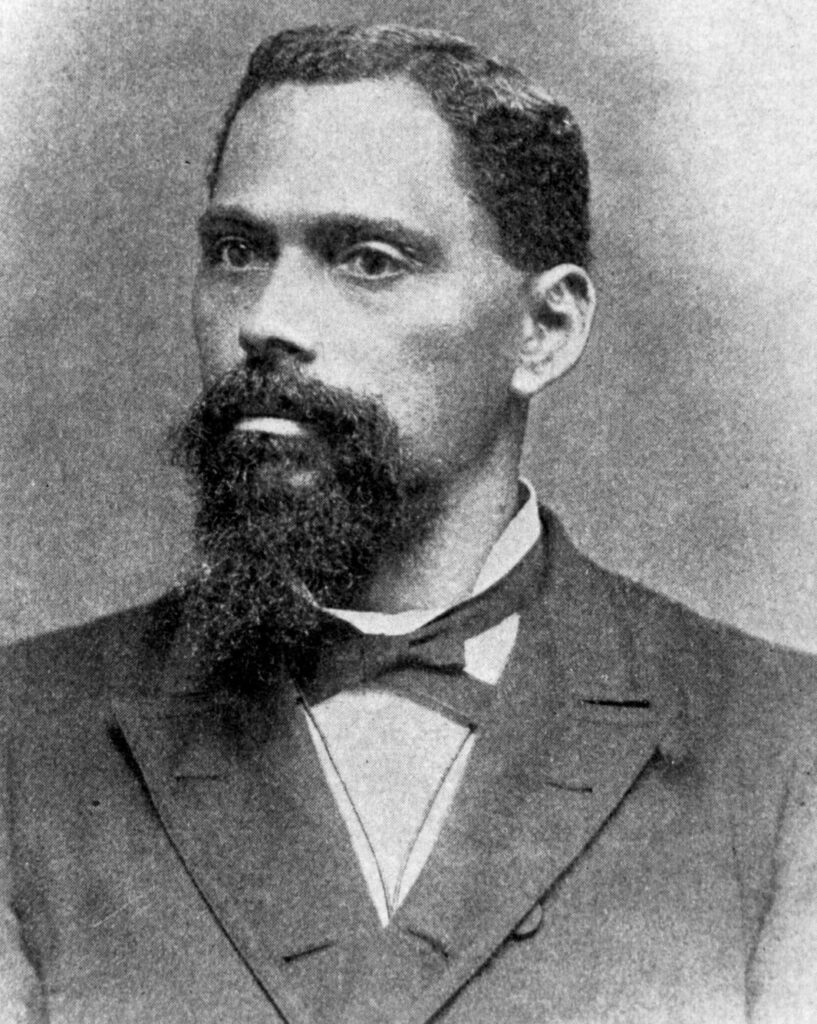

As bishop of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (later Christian Methodist Episcopal Church), Lucius Henry Holsey oversaw the growth of the denomination in his native state of Georgia. Through paternalistic interracial cooperation, he promoted collaboration between Black and white southern Methodists that resulted in a number of successes, such as the establishment of Paine College in Augusta.

Holsey, whose father was white, retained close ties with members of both races and worked for racial uplift even after, in exasperation over lynching and other racial proscriptions, he called on the American government to create a separate Black state in the West.

Born near Columbus in 1842 to an enslaved woman and her enslaver, Holsey later became the property of a white cousin who lived in Sparta, in Hancock County. The light-skinned redhead grew up among distant relations, some of whom taught him to read. With death approaching, Holsey’s second enslaver allowed Holsey to choose his next owner. Holsey chose the planter and educator Richard Malcolm Johnston, who in 1858 accepted a position as professor of English at the University of Georgia and relocated his family to Athens. There Holsey worked as body servant and carriage driver, and he continued his education, largely on his own. While attending a Methodist plantation missions revival led by the Black exhorter Henry McNeal Turner, Holsey converted to Methodism. When the Civil War (1861-65) suspended classes at the University of Georgia, the Johnston family returned to Hancock County, where Richard Johnston opened Rockby Academy and where Holsey met his future wife, the enslaved woman Harriett Turner. Turner was once owned by Johnston’s neighbor Bishop George Foster Pierce of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MECS).

As favored bondsmen, the Holseys received special treatment. Bishop Pierce performed the wedding ceremony for Turner and Holsey at his plantation home, Sunshine. With freedom at the end of the Civil War, Holsey received land from Johnston, while his wife took in the laundry of Rockby students. Pierce provided property for a Black congregation that Holsey led, Ebenezer Methodist Church.

During Reconstruction the white MECS decided to separate its Black members into a “colored conference” that could evolve into a distinct denomination. Organized in 1870, the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (CME) attracted many of the Black Methodists still attending white churches in the South. Holsey participated in the organizational meeting and received an appointment to Trinity CME Church in Augusta. When one of the Black bishops died in 1873, Pierce joined other white Methodists and the remaining Black bishop in the laying on of hands that signified the elevation of Holsey to the bishopric.

As a leader of the fledgling denomination, Holsey secured its footing and extended its membership among Black Methodists in Georgia. He founded a number of congregations, including Butler Street CME Church in Atlanta. He revised religious tracts, including a Manual of Discipline, and a hymnal for use in the CME Church. As secretary, he regularly attended the general conferences of both denominations to report on the activities of the CME bishops and to speak to the members of the MECS. Later in life Holsey published an autobiography that included a selection of sermons, as well as a volume of poems. Promoting biracial cooperation, the Black Holsey and white Bishop Atticus G. Haygood of the MECS traveled the South raising money for Paine College. This venture by Black and white southern Methodists underscored the potential of racial collaboration.

Yet by the turn of the twentieth century, vigilante violence, segregation ordinances, and disenfranchisement laws drastically altered life for many African Americans. At first Holsey joined other Black leaders in supporting the biracial efforts of the Populist Party, but after the 1899 brutal lynching of Sam Hose in Newnan, Holsey renounced paternalistic interracial cooperation in favor of Black separatism. He moved to Atlanta from Augusta and championed the idea of a separate state for Black Americans created by the federal government out of the Indian territories—a foolhardy plan perhaps, but one that Holsey hoped would allow some people of color to enjoy first-class citizenship.

Still holding to racial separation, he joined Black and white church leaders in an effort to restore order after the deadly Atlanta race massacre of 1906. Living on Auburn Avenue, where the King Center is located today, Holsey continued to influence the Black community as racial diplomat and bishop of the CME Church until his death in 1920.