Georgia’s statewide system of tuition-free public schools dates from the late nineteenth century. Because the architectural styles of school buildings vary from one time period to another and according to local district preference, Georgia’s public schools are often easily categorized by type.

A building type identifies the overall form or outline of the main or original part of the building, as well as the general layout of interior rooms. State funding for public education has varied from minimal support throughout the early nineteenth century to more substantial assistance through the state Board of Education (later the Georgia Department of Education), which was established in 1870. Both the amount of state funding and the directives that accompanied funds have influenced the construction of school buildings.

State Support for Public Education

Public schools in Georgia were first authorized in the Georgia Constitution of 1777, which provided that schools be established in each county at state expense. During the decades between the end of the American Revolution (1775-83) and the beginning of the Civil War (1861-65), a system of chartered academies partially funded by the state grew across Georgia. Academies, however, depended on tuition fees to meet operating expenses and were essentially private schools for free citizens only. Georgia law prohibited education for enslaved children. Beginning in 1822 the Georgia legislature provided modest funding to pay the tuition of children whose parents could not afford tuition costs. The “poor school fund” entitled a child to no more than three years of basic reading, writing, and arithmetic at public expense.

In 1858 state funding was provided to establish a free public elementary school system for all white children, but after the Civil War responsibility fell back on local governments, with only some wealthier areas able to provide continued schooling during the war years. Public schools expanded at the local level during the post–Civil War period, and for the first time, Georgia’s African American children had a legal right to obtain an education.

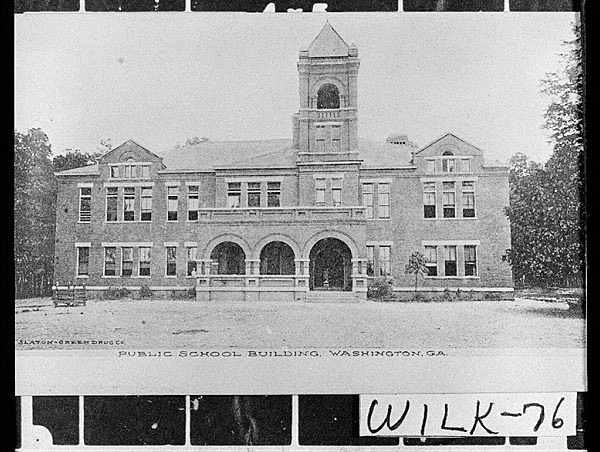

By 1874 every county in Georgia had at least some form of school organization, but Georgia’s post-Reconstruction Constitution of 1877 restricted state funding for education to elementary schools and the state university only. This left funding for public high schools contingent on those local governments that could afford such expenses. Incorporated cities and towns, but not counties, were also given the right to levy taxes on property within the town or city for the purpose of maintaining schools, and to issue bonds to construct and equip schools. Georgia’s county systems, with the exception of a very few that had previously established the right to levy property taxes for financing public schools, were left without the authority to raise funds to finance their schools, except through donations. While urban areas of the state took advantage of the opportunities to expand and improve their schools, rural counties were forced to subsist with little support for their school systems.

Beginning in 1905, the Georgia legislature passed a series of educational funding reforms. The McMichael Bill of 1905 required that each county be divided into school districts and given the right to vote to tax property for school funds. In 1912 the state school system was expanded to provide for public high schools. With the Barrett-Rogers Act of 1919, the Georgia legislature appropriated $100,000 to assist rural school districts with the costs of consolidating their many small schools into larger, more efficient facilities. These reform measures had a profound impact on the construction of public school buildings in Georgia.

Building Types

Five basic public-school building types exist in Georgia: one-room, two-room, linear plan, extended linear, and contemporary schools.

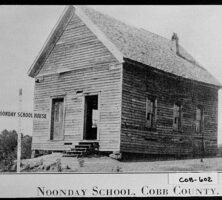

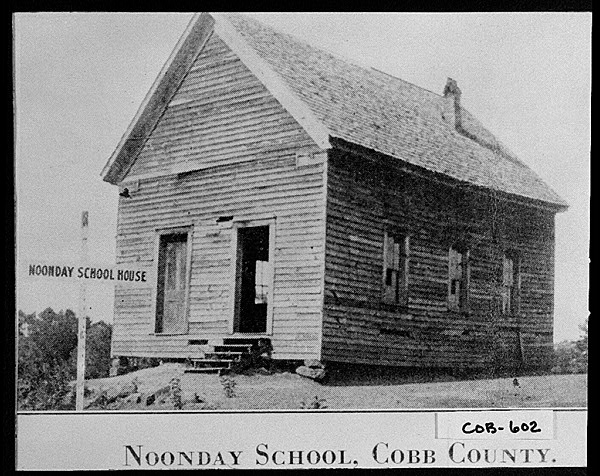

One-room schools existed in all areas of the state prior to 1900 and in many rural areas and small communities even as late as the 1940s. These schools were generally rectangular in form and constructed of wood. Typically a bank of windows ran along the side walls for light and ventilation, but there were no windows in the facade wall.

Two-room schools were constructed in rural areas and small communities from around 1900 to about 1940. They featured two classrooms divided by a central hallway or vestibule. Ribbons of windows lined the exterior classroom walls. From 1917 to 1932 the Julius Rosenwald Fund provided grants to local school systems to help build new schools for African Americans in rural communities of the South. Of the 242 schools constructed in Georgia with the aid of Rosenwald funds, many were one- or two-room school buildings.

Linear plan schools were constructed during the expansion and consolidation phases of public school systems in the early twentieth century. They existed in rural areas and small to large communities throughout Georgia. These schools featured a projecting central entrance or, in some cases, a recessed central entrance. A main corridor was lined on both sides with classrooms. While many were only one story in height, multistory examples of this type served neighborhoods in larger towns and cities. These schools were typically of brick construction.

Extended linear school buildings were constructed statewide in midsize to large towns and cities from the 1920s through the middle of the twentieth century. This type of school building featured a three-part main block and had one or more wings projecting from the rear of the main block. The overall shape typically formed an E, T, or U. Most were one story in height and constructed of brick. The projecting wings of these schools generally served specialized purposes, such as auditoriums, cafeterias, gymnasiums, or science laboratories.

Contemporary school building types have evolved since the 1970s, when educational planners began to confront new and complex issues through the design of school facilities. Concerns about energy conservation and security monitoring, barrier-free accessibility and accommodations for students with special needs, and the rapidly changing role of technology in the classroom are all reflected in the architectural designs of modern-day schools. While many communities have successfully rehabilitated and expanded historic, community-centered school buildings to meet current needs, others have constructed new facilities. Such new facilities are often sprawling structures that may contain hundreds of thousands of square feet of interior space. They are typically asymmetrical in design and may feature a central core or node that provides space for administrative offices and the main media center, while classroom corridors extend away from the central core, like spokes in a wheel or in a variety of other configurations.

Examples of the earliest school building types can still be found in Georgia. Some have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places and restored as museums or for other community uses. The Chestnut Grove School near Athens, built in 1896, is typical of one-room school buildings that served rural areas of the state. The building has been restored as a community center. In Bartow County the two-classroom Noble Hill School (1924) has been restored as a community heritage museum.

Later examples, such as the Winnona Park Elementary School (ca. 1924) in Decatur and Booker T. Washington High School (1924) in Atlanta, have been expanded and continue to serve as educational facilities. The original four-story Washington High School building was constructed from 1922 to 1924 and has a projecting central entrance flanked on either side by classroom corridors. The first expansion of Washington High, in 1937, was a Works Progress Administration (later Work Projects Administration) project that added a science laboratory and six classrooms along the north end of the school.

Other buildings that once served as community schools have been adapted for use as living spaces, professional offices, or civic centers. In a growing number of Georgia communities, citizens are beginning to question the practice of moving students out of historic neighborhood schools and into large campuses outside of town. Parents are responding to a recent National Trust for Historic Preservation initiative aimed at preserving neighborhood schools, and they are working with school boards and administrators, as well as with state and local preservation organizations, to find ways of rehabilitating older school buildings.