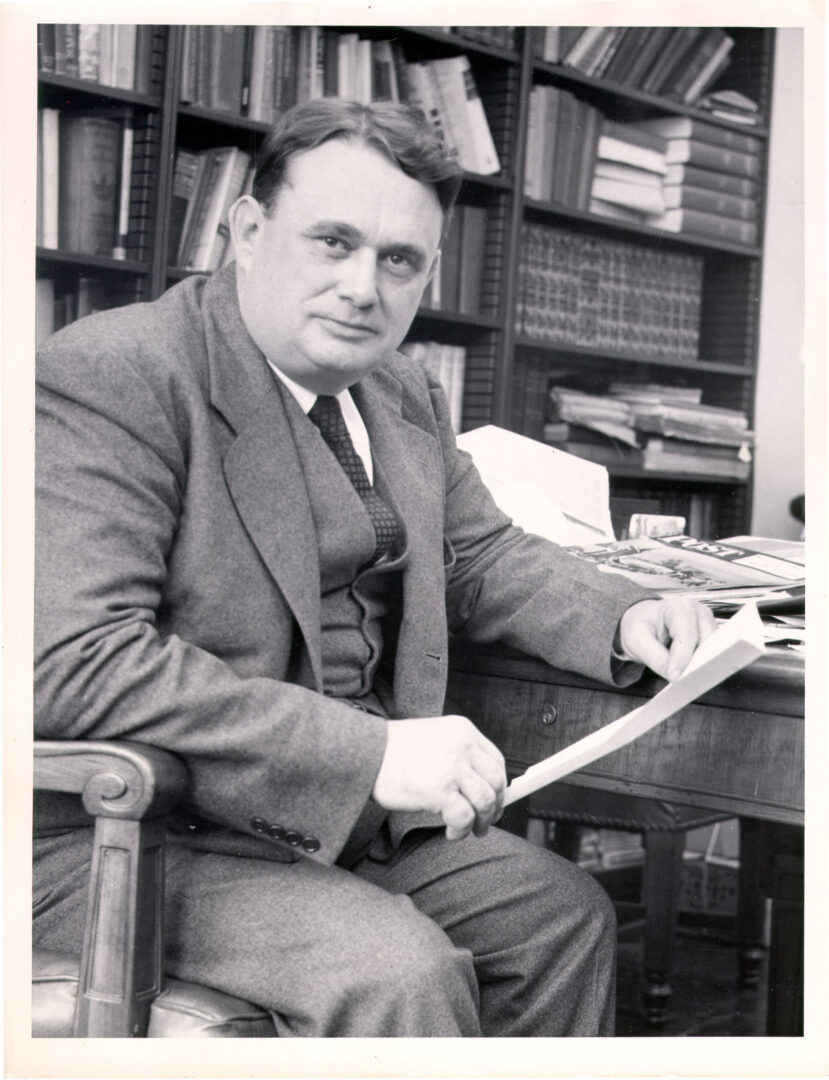

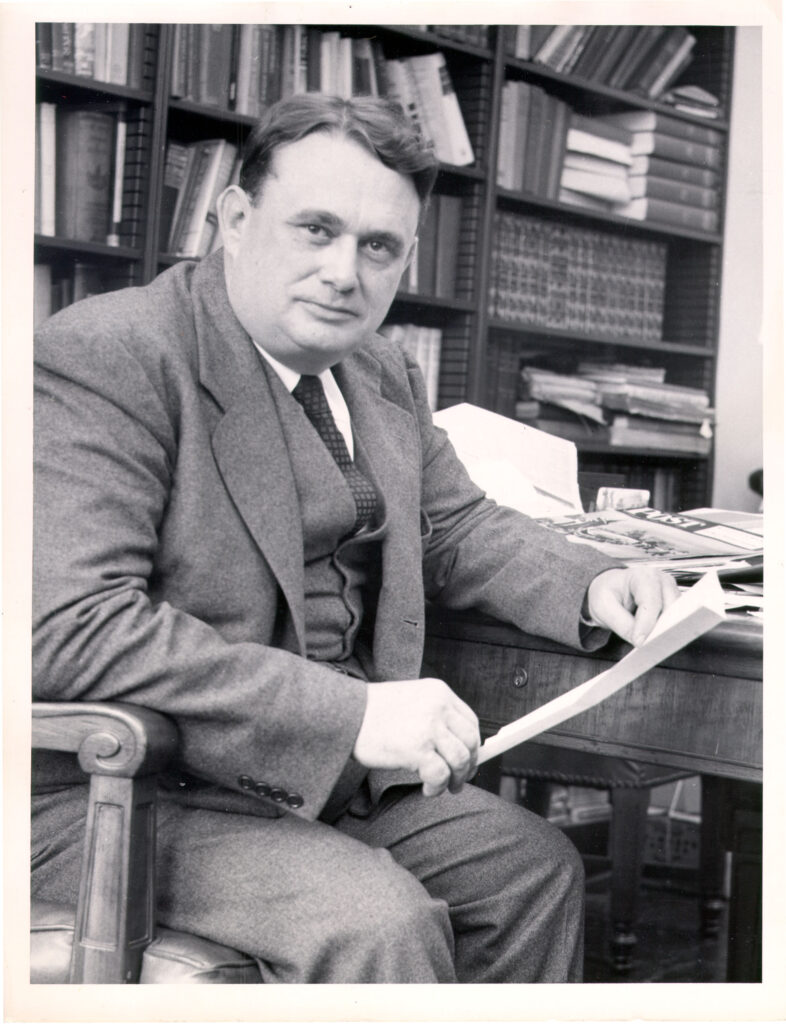

Ralph McGill, as editor and publisher of the Atlanta Constitution, was a leading voice for racial and ethnic tolerance in the South from the 1940s through the 1960s.

As an influential daily columnist, McGill broke the code of silence on the subject of segregation, chastising a generation of demagogues, timid journalists, and ministers who feared change. When the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregated schools in 1954 and southern demagogues led defiance of the court, segregationists vilified McGill as a traitor to his region for urging white southerners to accept the end of segregation. In 1959, at the age of sixty-one, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing.

Early Life

Ralph Emerson McGill was born on February 5, 1898, in the remote farming community of Igou’s Ferry, about twenty miles north of Chattanooga, Tennessee. He was the second son (the first died as an infant) of Mary Lou Skillern and Benjamin Franklin McGill. McGill graduated from the McCallie School in Chattanooga and between 1917 and 1922 (with time out for service in the U.S. Marines in 1918-19) attended Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, but he did not graduate. In his senior year he was suspended after writing a column in the student newspaper that suggested wrongdoing because Vanderbilt had not erected a student lounge, as stipulated in the will of a professor who had bequeathed the school $20,000. McGill might have appealed to return to graduate, but he had found a full-time job as a reporter for the Nashville Banner, and as a colleague noted, “the degree didn’t mean that much to him.”

During the 1920s McGill became the Banner’s sports editor and sports columnist, but he eagerly looked for opportunities to break away from the seasonal sports routine to cover murder trials and political campaigns. Friendships with other southern sportswriters led him in 1929 to the Atlanta Constitution, as assistant sports editor and later sports editor and columnist. Also in 1929 McGill married Mary Elizabeth Leonard, the daughter of a dentist, whom he met when he interviewed her brother, a Vanderbilt football star. They had a daughter, who died days after her birth. Shortly thereafter the couple adopted a baby girl, and she died a few years later from leukemia. A son, Ralph Jr., was born in 1945. McGill’s wife died in 1962, and in 1967 McGill married Mary Lynn Morgan, an Atlanta children’s dentist.

Early Atlanta Career

McGill’s distinct writing voice established him as a popular talent, giving the morning Constitution an edge over the two afternoon papers, the Atlanta Georgian, owned by the William Randolph Hearst chain, and the Atlanta Journal. As in Nashville, his enormous energy and sense of timing secured him opportunities to write on serious subjects. In 1933 he got his first break in international journalism, persuading the Constitution to send him to cover the Cuban revolution. His datelined stories, including an exclusive interview with dictator Gerardo Machado days before he fled, were displayed on the front page of the paper, establishing McGill as a serious journalist.

McGill completed his transformation to serious journalism after he won a Rosenwald Fellowship, freeing him to study and write from Europe during the first six months of 1938. From Vienna, Austria, his front-page accounts of Adolf Hitler’s seizure of that country earned him a promotion to editor of the editorial page when he returned to Atlanta.

From June 1938 until his death in February 1969, McGill wrote daily, more than 10,000 columns. In 1942 he was promoted to editor-in-chief of the Constitution, and in 1960 to publisher. For much of his career he was a lone voice in Atlanta journalism, breaking the white code of polite silence about social and educational segregation and political disfranchisement—the so-called situation, or “sitch.”

The Conscience of the South

Between 1938 and 1954 McGill courageously portrayed the South’s failure to live up to the “separate but equal” ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896. Without advocating integration, he described the deplorable conditions of Georgia’s Black schools, comparing their budgets for books and buildings with those of white schools. In the political arena he noted that one day African American voters would have considerable influence.

McGill understood that he could not write unrelentingly about civil rights and still keep his audience. In sportswriting he had chronicled pitchers who cleverly mixed their pitches, and he adopted that pattern: he mixed his columns, writing one day about barbecue, then about a charity, then about a newsworthy Atlanta citizen, then a sports column, and then, again, the “sitch.” A notable column in 1953, “One Day It Will Be Monday,” presaged the Supreme Court’s ruling that would outlaw the system of dual societies: “So, somebody, especially those who have a duty so to do, ought to be talking about it calmly, and informatively.”

For such comments segregationists vilified him. They telephoned his home and wrote letters, often with misspelled words, which he found somewhat humorous and shared with his small group of likeminded “brethren” editors across the South, among them Harry Ashmore at the Arkansas Gazette and William C. “Bill” Baggs at the Miami News. Segregationists branded McGill as “Rastus,” a Communist, a traitor. His colleague Jack Tarver noted that the Constitution’s polls showed readers were evenly divided between those who loved him and those who reviled him, that some could not eat breakfast without reading McGill and others could not eat breakfast after reading him.

All these emotions erupted after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. The U.S. Supreme Court ruling and southern governors’ resistance forced the issue of segregation out of the sanctuary of silence. McGill sided with the law of the land, which meant a radical reorientation of a society that for generations nurtured legal segregation from the rest of the nation.

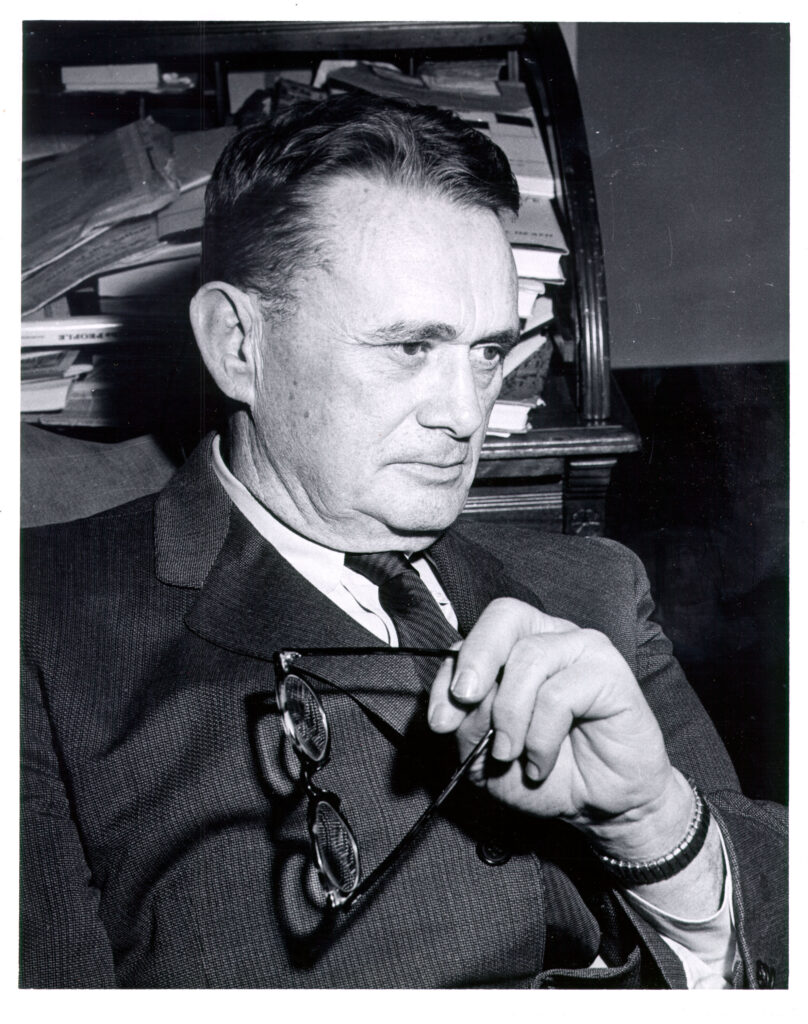

During the late 1950s and 1960s McGill made another career transformation, becoming a national voice as a syndicate circulated his column to hundreds of newspapers. With his national audience in mind, McGill traveled frequently to Washington, D.C. As a lifelong Democrat, he gained an inside political track during the administrations of U.S. presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Both presidents sent him on cold war ambassadorial trips to newly independent nations in Africa to persuade leaders that the United States was working to solve its civil rights problems.

Intimacy with the presidency had a downside. McGill, as a loyal Democrat and a former marine, was unwilling to criticize America’s war in Vietnam. In general, he was more likely to be correct about what was closest to his heart and soul—the South—than about the other worlds he reached out to—distant cultures where he was not a citizen but a sojourner.

Two things were clear to McGill’s appreciative contemporaries. The first was that he spoke and wrote unfalteringly what he thought and felt, and in doing so he inspired others to break the silence. He had a poet’s facility with language and a journalist’s ease with the medium. In the last months of his life, he repeated a central article of faith—that “the desire for individual dignity and freedom . . . is in the genes of all mankind.”

The second reality was his bedrock intellectualism—a never-ending appetite for scholarship. Few public men read so ravenously as McGill, and few understood as much and communicated it to so large an audience—an audience that was often unready and frequently hostile. McGill consciously employed his mind methodically, he developed habits that made him work his mind tirelessly, and he found the conditions that encouraged him to study, to write, and to publish daily.

Book Publications

McGill published four books over the course of his career. The first three consisted primarily of compilations of his newspaper columns. One of these three, A Church, a School (1959), comprised his editorials on the Temple bombing in Atlanta and on hate crimes by the Ku Klux Klan. It was these editorials for which McGill won the Pulitzer Prize in 1959.

His most notable book was the The South and the Southerner, first published in 1963. A selective memoir of his East Tennessee upbringing and various facets of his journalistic career, it is also a much broader social commentary on and sharp critique of the South, past and present, though it also reflected his optimism for the region’s capacity for progressive change.

McGill died suddenly of a heart attack in Atlanta on February 3, 1969, just two days before his seventy-first birthday. In 2004 he was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.