As a performer and recording artist in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Ray Charles pioneered a new style of music that became known as “soul,” a blend of gospel music, blues, and jazz that brought him worldwide fame. Over the next four decades his unique voice, passionate style of playing the piano, and tireless showmanship made him a legendary figure in the world of entertainment.

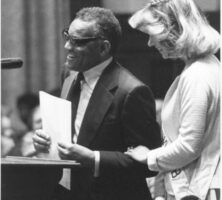

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

In the popular imagination Ray Charles will probably always be linked with his rendition of “Georgia on My Mind,” his number-one pop hit of 1960. Over the next forty years, this “old sweet song” remained his signature piece, becoming Georgia’s official state song in 1979.

Early Years

Ray Charles Robinson was born in Albany on September 23, 1930, the same year that Hoagy Carmichael composed “Georgia on My Mind.” A few months after his birth his mother, Aretha Williams, moved with RC (as everybody called the young Charles) to Greenville, a small town in north Florida.

At the age of five Charles slowly began to lose his sight, most likely as a result of congenital juvenile glaucoma. In the same year his younger brother drowned. Despite these setbacks and dire poverty, his mother pushed Charles toward greater independence. After he was declared legally blind at the age of seven, she enrolled him in the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind in St. Augustine, where he remained for nine years, until her death in 1945.

As Charles describes in his 1978 memoirs, his early years were filled with music. Although no one in his family was a musician (his mostly absent father, Bailey Robinson, was a railroad employee), he found music in every direction: the raw, emotional sounds of gospel music in the church, the jukebox at the general store that blasted out the blues, the boogie-woogie that the store owner would play on piano with the attentive young boy at his side. Charles also listened to big band music on the radio, along with hillbilly tunes from the Grand Ole Opry. At the school for the blind, Charles learned to read music and play Frederic Chopin, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Johann Strauss. Over time he also discovered jazz music and a deep appreciation of jazz pianist Art Tatum.

Professional Years

In 1945 the fifteen-year-old Charles left school to make his living as a professional musician. His early travels took him to nearby Jacksonville and Orlando, Florida, where his reputation grew as a versatile piano player, saxophone player, and arranger who could handle blues, jazz, boogie-woogie, swing, or hillbilly. He imitated the smooth vocals of popular singers Charles Brown and Nat King Cole, and wouldn’t develop his own singing style for at least another decade.

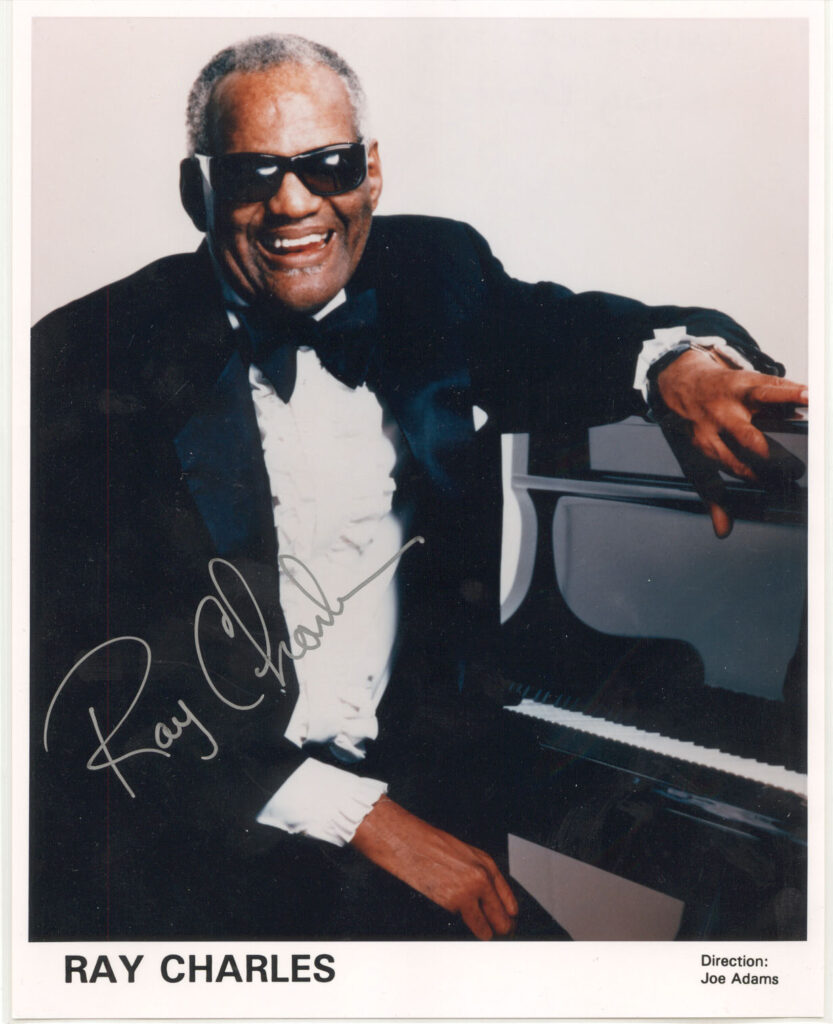

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

After his move to Seattle, Washington, in 1948 to pursue better career opportunities on the West Coast, Charles’s show-business persona began to emerge. He dropped his last name to avoid possible confusion with the well-known boxer Sugar Ray Robinson. He also began wearing the dark glasses that would become his trademark. More important, he recorded his first song, which he followed the next year with his first national hit on the Black charts (“Baby, Let Me Hold Your Hand”). At the time Black culture was isolated and largely ignored by white mainstream culture, which accepted only a few Black musicians, including Brown and Cole, as well as Fats Waller, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong.

In 1950 Charles moved to Los Angeles, California, which later became his permanent home and the location of his private recording studio, to seek his own popular success and financial independence. For the next few years he toured on the road, playing behind other musicians, often enduring long trips through the segregated South.

Soul Years

Once Charles began traveling, performing, and recording with his own band, the voice that would become his trademark took shape. His 1954 rhythm-and-blues hit for Atlantic Records, “I Got a Woman,” was an electrifying synthesis of gospel music, blues, jazz, and boogie-woogie that became the pattern for future hit songs. It also brought howls of protest from those who claimed his music was sacrilegious.

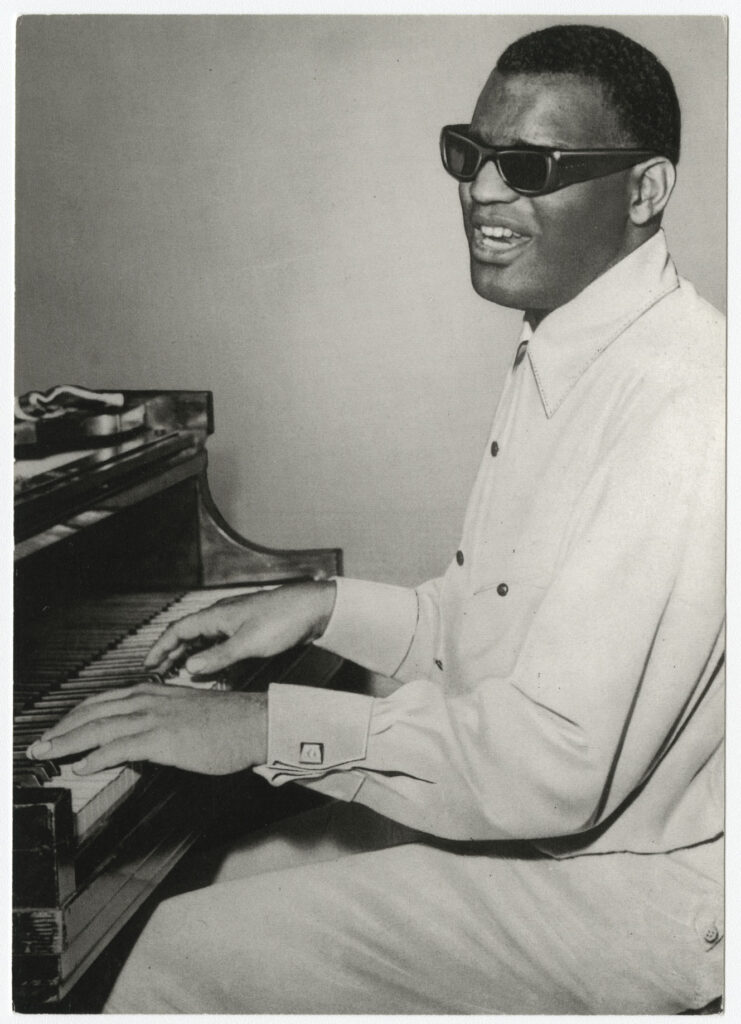

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Charles insisted that he was only doing what came naturally—playing the music that came straight from his soul. By doing so, he appealed to a youthful audience of Blacks and whites alike who supported a new generation of energetic young Black musicians that included Charles, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard.

Toward the end of 1955 Charles began experimenting with female backup singers, taking his cue from girls’ gospel groups. Once he discovered the combination of feminine harmony with his strong, masculine vocals, he made the Raeletts a permanent addition to the band in 1957. By that time all the elements that would define Charles’s unique style were in place: the gruff vocals that could express any degree of loneliness or exuberance, the expressive piano playing, the professional backup musicians who could follow his lead wherever he wanted to go, and the backup singers.

Over the next few years Charles recorded three number-one pop hits. “Georgia on My Mind” (1960) was followed by “Hit the Road Jack” (1961) and “I Can’t Stop Loving You” (1962). The last song was included on a country and western album that surprised many critics and fans, but he insisted that it was a natural expression of his musical heritage.

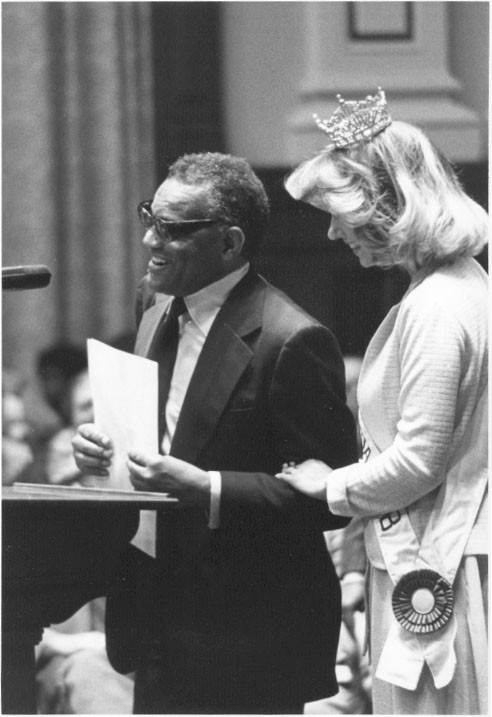

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Charles’s performing and touring did take a toll on his personal and family life, however. His second marriage, to Della Howard, produced three children, but two paternity suits in the early 1960s revealed that he had fathered several more children out of wedlock. In 1964 he was arrested for possession of heroin and later admitted that he had been addicted since the late 1940s. After a period of rehabilitation at a California sanitarium, Charles kicked his drug habit and received a five-year suspended sentence.

Legacy

Charles’s music and reputation endured into the twenty-first century. His vibrant personality reached a new generation of fans in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers and in a 1990 Diet Pepsi commercial. He was the first performer inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame (1979), and he is also honored in the Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame (1982 )and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1986). He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1993. Charles died on June 10, 2004, of acute liver disease at his home in Beverly Hills, California.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

In the months following his death, the legacy of Ray Charles continued to grow. A final album, Genius Loves Company, was released in September 2004 and consists of duets with twelve prominent singers. Charles’s duet with Norah Jones, “Here We Go Again,” won the Grammy Award for Record of the Year, while Genius Loves Company won the Grammy for Album of the Year. The motion picture Ray, which opened in October 2004, chronicles his childhood and career through the 1960s. Directed by Taylor Hackford, the film features Jamie Foxx as Ray Charles in a widely acclaimed performance that garnered the actor both Golden Globe and Academy awards.

Photograph by Meg Inscoe

A special exhibition of memorabilia and video recordings entitled “The Genius of Ray Charles” opened in November 2004 at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, and in September 2005 Rhino Records released Pure Genius: The Complete Atlantic Recordings (1952-1959), a CD/DVD boxed set.

The Ray Charles Plaza in Albany, which commemorates the singer with a bronze revolving statue, opened in December 2007.