In early-twenty-first-century Georgia, stadium-sized revival meetings featuring Billy Graham or the Promise Keepers attract tens of thousands of people. Such revivals are the modern-day descendants of early-nineteenth-century camp meetings, held on grounds around the state, and a method of evangelical preaching that gained popularity in the late eighteenth century.

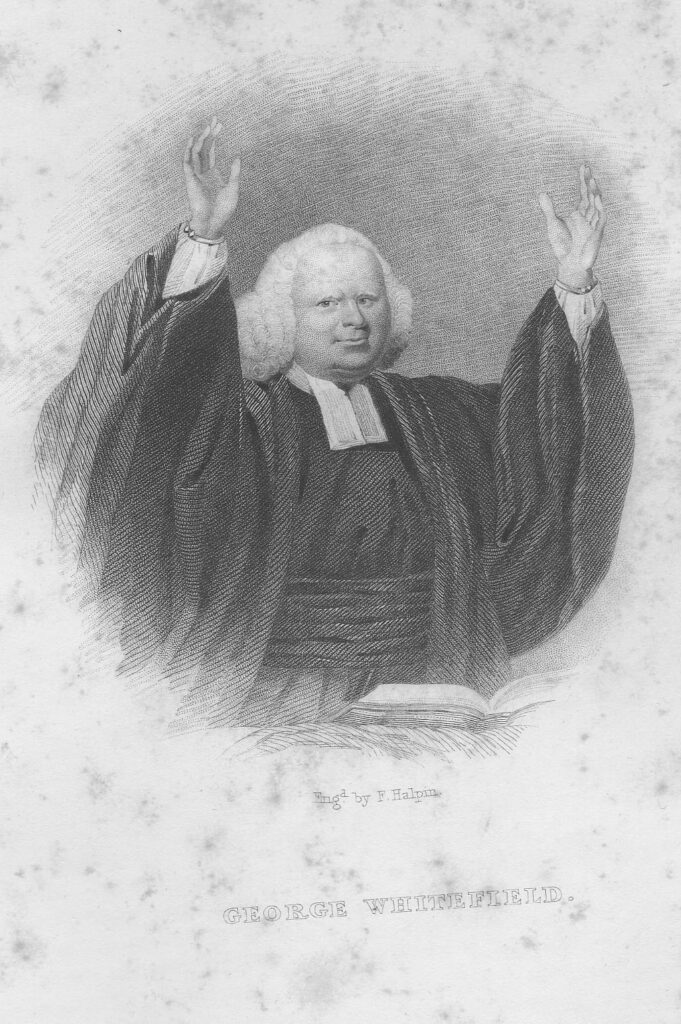

The tradition of revivalism in the South, and in Georgia in particular, traces its roots to what some historians call the Great Awakening. The Great Awakening, which occurred from about 1720 to 1780, was a series of revivals that sparked a move away from formal, outward, official religion to experiential, inward, personal religion. Its central figure, George Whitefield, was a traveling Anglican preacher from England who cooperated with Protestants of every sort to gain converts.

From his home base in Savannah, Whitefield brought a riveting new preaching style to the colonists. He spoke extemporaneously rather than read from a prepared sermon; he spoke to, not at, his listeners; he used pamphlets and newspapers to promote his sermons; and he used emotional entreaties rather than formal theology to convert thousands.

In Georgia and throughout the colonies Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians took Whitefield’s revival message to heart. Never having had the advantage of state support, these democratic-minded churches adopted the revivalist themes of individual exertion, earnest preaching, and soul searching. Democratic in its appeal and egalitarian in its preaching, revivalism fit the social and political spirit of the new nation. Members of the lower and middle classes were empowered by the Evangelical Protestantism preached by revivalists, through which they achieved identity and solidarity. Soon Methodist circuit riders and Baptist farmer-preachers replaced learned pastors as leaders of those churches. Whitefield and other itinerant preachers went out of their way to preach to all persons, including enslaved African Americans. By 1773 there was an independent African American church in South Carolina, and soon similar churches sprang up in Georgia and Virginia.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Revivalism took many forms. In the East revivals were carefully guided and disciplined affairs, governed by itinerant evangelist Charles Finney’s “new measure” techniques. But Finney was merely taming the more exuberant forms of revivalism, especially the camp meeting, that were born on the western frontier. Camp meetings lasted up to five days and featured revival preaching day and night. Whites, Blacks, men, women, and persons of all denominations took turns exhorting would-be converts. Repentant sinners were asked to approach the “anxious bench,” where they sat with all eyes on them until they were converted to Christ’s cause. Camp meetings induced sensational results: some observers described participants laughing out loud, barking like dogs, falling down as if dead, and experiencing “the jerks.” During the so-called Second Great Awakening, from about 1790 through 1830, camp meetings became one of the most popular ways to preach the revival message.

The first recorded camp meeting in Georgia took place in 1803 on Shoulderbone Creek in Hancock County. Methodist preacher Lorenzo Dow, who witnessed that meeting, was so impressed that he took the concept back to England, where he duplicated it with much success.

Camp meetings were popular with rural Georgians. Not only a time for spiritual renewal, camp meetings were also gathering grounds where families and friends could reunite. In the nineteenth century most Georgians were farmers who lived solitary, demanding lives. Camp meetings were festive affairs celebrated annually at a time when crops were laid by, thus providing a reprieve from the rigorous routine of farm life.

But by the late nineteenth century Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians around Georgia disdained the behaviors and emotionalism associated with the camp meeting. In the latter half of the century these denominations had become the most powerful in the state, and it was the emerging Holiness and Pentecostal groups who embraced the egalitarian camp meeting. While these groups maintained the tradition of holding extended revival meetings, they shed the excessive emotional attributes that marked early camp meetings. Today there are nearly 100 active Methodist, Holiness, and Pentecostal camp meeting sites in Georgia each year. Camp meetings are still used to reinvigorate churches through extended revival meetings.

Since the Great Awakening the purpose of the revivals has remained the same: to convert sinners to Christ. And while the camp meeting tradition has changed, the revivalist techniques of George Whitefield, Lorenzo Dow, and Charles Finney still thrive in today’s Evangelical Protestant churches.