From small, idiosyncratic drawings to elaborate outdoor environments, Georgia’s self-taught artists have made significant contributions to the state’s artistic heritage.

Many of these self-taught artists—so called because they received no formal artistic training—began to make art after life-changing experiences such as an illness, a religious vision, or retirement. In the late twentieth century, as Georgia’s artists began to gain international recognition, the state became known as a bastion of self-taught art.

Georgia artisans of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries largely produced crafts and objects that reflected the utilitarian needs of the era. Occasionally an artist emerged from prevailing traditions to produce works of great originality and profound expression. The quilter Harriet Powers of Athens was such an artist. Born into slave status, Powers is known through two pictorial appliqué quilts that use biblical and folkloric imagery in a style that has been likened to Dahomean pictorial textiles of Africa. The earlier quilt (ca. 1886) is housed at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. The later quilt (ca. 1895-98) is housed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts.

Early Twentieth Century

Numerous self-taught artists emerged in early-twentieth-century Georgia. In Meigs, a small town in Thomas County, in south Georgia, Laura Pope Forester began making concrete figures, many commemorating important women in history and literature, including Nancy Hart, a heroine of the Revolutionary War (1775-83), and Scarlett O’Hara, the protagonist of Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone With the Wind (1936). Forester’s “Mrs. Pope’s Museum” in Thomas County, which reopened in 2018 thanks to local preservationists, was one of Georgia’s earliest outdoor self-taught art environments.

The era of the Great Depression spawned a number of “make-do” objects and crafts as people scrambled to make a few pennies. Georgia artisans like David Carter of Savannah, for instance, made rustic furniture from twigs, occasionally embellished with carved snakes. By the 1930s professionally trained artists and collectors began to notice and encourage the productions of self-taught artists like William O. Golding, a Black seaman from Savannah. Golding made more than sixty lively pencil-and-crayon color drawings of ships and exotic ports during his stints in the U.S. Marine Hospital at Savannah. In the coastal town of Darien, William Rogers, an African American preacher, made walking sticks and animal carvings reminiscent of African art.

Late Twentieth Century: Exhibitions and Recognition

Georgia’s self-taught art reached its full flower in the late twentieth century. The 1976 exhibition Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art, 1770-1976, shown at the Atlanta Historical Society in Atlanta, the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences (later Telfair Museums) in Savannah, and the Columbus Museum of Arts and Crafts (later the Columbus Museum) in Columbus, was the first attempt to gather the state’s nonacademic art into a traveling museum exhibition. This show represented the first major exhibition opportunity for such noted Georgia artists as Howard Finster, Nellie Mae Rowe, and Ulysses Davis.

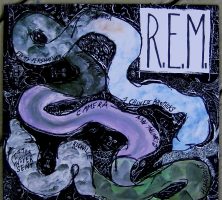

Other national exhibitions followed, including Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980, at the Corcoran Museum of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1982, which featured the work of Rowe and Davis. Rock music videos and album covers for popular music groups like R.E.M. and the Talking Heads featured the work of Finster and R. A. Miller. Finster was chosen to represent America in the Venice Biennale of 1984. Today, works by Georgia’s self-taught artists are represented in the collections of virtually all the state’s art museums and are found in major private and public art collections around the world.

Artists in Geographical Context

Southeast and South Central Georgia

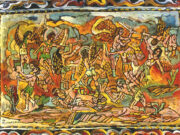

In Savannah, Ulysses Davis established a barbershop, where he alternated between cutting hair and carving wood. Best known for his carvings of U.S. presidents, Davis inspired other African American woodcarvers, including Arthur “Pete” Dilbert and Vernon Edwards. The blind Savannah artist Captain William E. Jordan produced hundreds of color-pencil landscape, still life, and abstract drawings between 1957 and 1964. Painter Rudolph Valentino Bostic from Savannah paints scenes from the Bible and popular culture, rendered in a “make-do” reinvention of such old-master painting techniques as chiaroscuro, the use of light and shade to create depth.

Willie Tarver of Wadley, in Jefferson County, sculpted imaginative human and animal figures in both concrete and welded metal. South of Augusta, in Girard, Ralph Griffin made red-, black-, and white-painted figures from found tree trunks and roots. After experiencing a vision of an angel, Zebedee “Z. B.” Armstrong of Thomson created wooden sculptures and calendars marking the countdown to the end of time. His constructions are painted white with gridlike markings in black and red. Another Georgia visionary, J. B. Murry (sometimes spelled as “Murray”) of Sandersville, in Washington County, drew small, ecstatic abstractions composed of indecipherable writing and spirit figures—a visual equivalent to the religious practice of speaking in tongues.

Northeast Georgia

Near the University of Georgia campus in Athens, Dilmus Hall created a sculptural yard environment of concrete, metal, and wood figures; crayon, graphite, and ballpoint-pen drawings inspired by the Old Testament; and smaller concrete sculptures of animals and people, including a relief sculpture of physician Crawford Long. In Gainesville R. A. Miller made metal cutouts, whirligigs, and paintings, often using flat, simplified figures of humans and animals combined with spiritual messages. George Andrews of Madison, the father of noted artist Benny Andrews and writer Raymond Andrews, was known as the “Dot Man,” for his funky paintings decorated with dots on found objects, such as rocks and furniture, and on canvas. Carlton Garrett of Flowery Branch made colorful wooden sculptures, often using metal and other materials. “Memory painter” Mattie Lou O’Kelley from Maysville, in Jackson County, began to paint in 1962, at the age of fifty-four. Memory painters like O’Kelley were known for depicting scenes from their earlier lives—usually rural themes reflecting simpler times.

Atlanta

Atlanta-area artists include Nellie Mae Rowe, who began drawing and creating a yard environment of stuffed dolls wearing wigs, chewing-gum sculptures, and plastic toys after the death of her second husband in 1948. Rowe’s works received notice from galleries, collectors, and curators in the state and nationally, and she has been the subject of museum exhibitions. Painter Lorenzo Scott was inspired by the work of Renaissance masters he viewed in New York and Atlanta museums. Archie Byron, a former private detective and Atlanta city councilman, created sculptural reliefs and freestanding figures with a modeling compound made from sawdust and glue. The Atlanta woodcarver Ned Cartledge was known for his humorous and stinging social commentary. One of his carvings, for example, depicts U.S. president Ronald Reagan pulling a skunk out of a magician’s hat.

Northwest Georgia

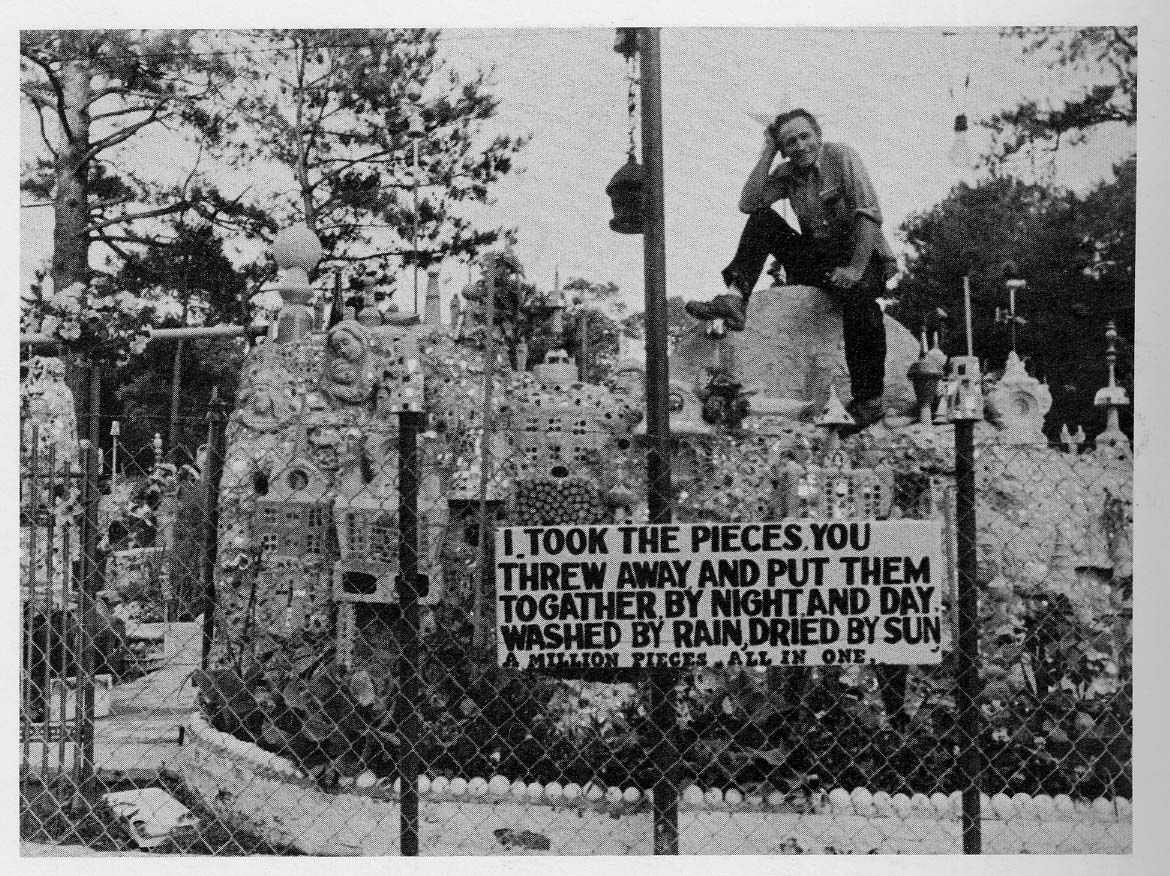

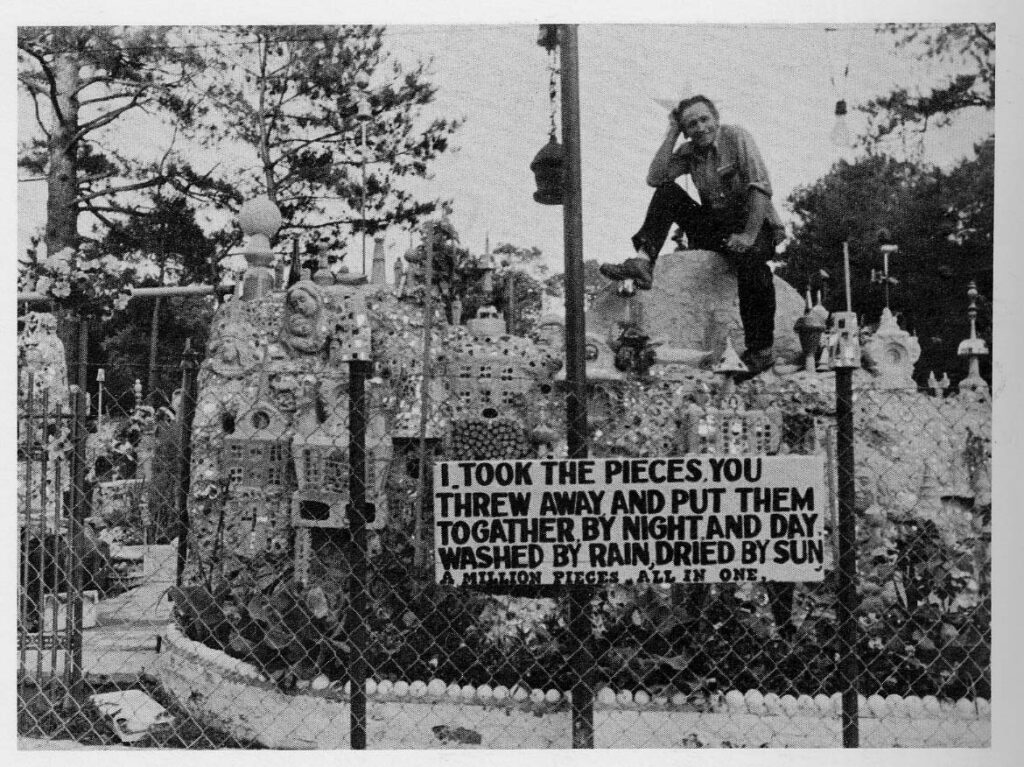

Northwest Georgia was home to the Reverend Howard Finster, of Chattooga County. Finster became Georgia’s most famous artist, achieving international notice through his appearance on NBC’s Tonight Show, the inclusion of his work in international exhibitions, and the reproduction of his works on album covers and books. Finster’s work combines evangelical and commemorative messages with references to popular culture. He claimed to have received a call from God compelling him to make art and to create his “Paradise Garden,” a sculpture garden filled with mixed-media creations next to his house in Pennville. Finster painted on plywood, canvas, or gourds and created sculptural objects from found materials. Major components of his Paradise Garden are now in the collection of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.

Southwest Georgia

Eddie Owens Martin, also known as “St. EOM,” created a mystical environment of totemic figures and buildings in Buena Vista, in Marion County. “Pasaquan,” as Martin called his monumental creation, is still open to the public and is one of the largest folk art environments in Georgia. The site is preserved and operated by Columbus State University, which assumed full ownership of Pasaquan in 2016.