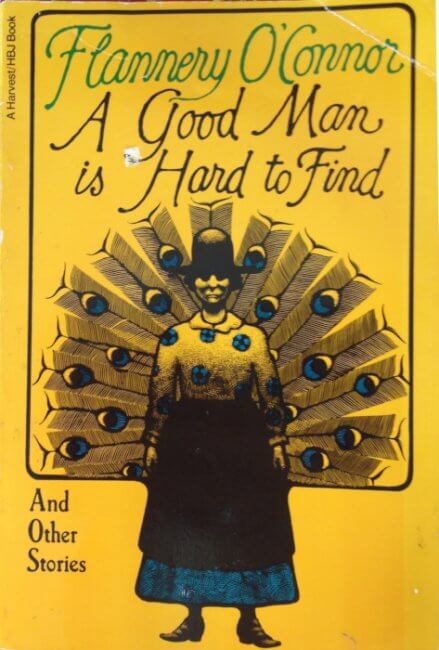

Economy of form, biting satire, vivid characterizations, and a stern moral vision are the defining characteristics of Flannery O’Connor’s short fiction. Her reputation as a short-story writer rests on two volumes, only the first of which appeared in her lifetime: A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955). Everything That Rises Must Converge was published in 1965, a year after her death from lupus.

O’Connor began writing fiction in earnest at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the late 1940s. During her apprentice years there, she enjoyed the advice of such older writers as Paul Engle, Caroline Gordon, Robert Lowell, Andrew Lytle, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren. Shortly after completing her master’s thesis, a group of stories entitled “The Geranium,” she won the Rinehart-Iowa Fiction Award for her unpublished first novel: Wise Blood was published in 1952, and soon after, she began to write the stories for which she is renowned.

Style

O’Connor’s stories are set in the modern South, more often in the country than in the city. Many are placed on farms similar to the one on which she herself lived. The main character is often a middle-aged, middle-class w oman living on her own, with responsibility for a farm. Less often the protagonist is a child, usually a young girl, or a young man. All her protagonists have well-established views of themselves, of human nature, and of the world. They attempt to order their lives in accordance with their views of the world. The pattern of action in the stories moves toward a moment in which the main characters recognize the falseness of their views.

Image from National Book Foundation

Often the catalyst for this recognition is another character, either an outright antagonist, such as the Misfit in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” or the Bible salesman Manley Pointer in “Good Country People,” or a lower-class woman whose opinions clash with the protagonist’s, serving as a foil to her. In “A Circle in the Fire” Mrs. Pritchard, who works for the main character, Mrs. Cope, serves this function. Her fascination with a woman in an iron lung who died in childbirth irritates Mrs. Cope and her desire to run an orderly, upright farm. O’Connor typically works to deflate social and intellectual pretensions—as she does in “Everything That Rises Must Converge” and “The Enduring Chill”—or even to portray them as evil.

Themes

O’Connor’s stories typically set opposing forces against one another—the modern secular world with its emphasis on science, social programs, humanism, and progress, and the God-centered spiritual world, with its emphasis on sin and salvation. This pattern is almost always present, but the stories are not formulaic, and they vary considerably in situation and in character.

O’Connor examines other concerns as well. She is especially effective in portraying the consciousness of a character on the verge of enlightenment, change, or transformation, as in “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” “A Stroke of Good Fortune,” and “Parker’s Back.” She also wrote several successful stories about race, the best-known of which is “The Artificial Nigger,” in which two inhabitants of the north Georgia mountains visit Atlanta, encounter African Americans for the first time, and discover the meaning of racism in a lawn ornament.

The Collections

Most of the stories in A Good Man Is Hard to Find had been published in literary journals by the time the collection appeared. The title story is about a middle-class Atlanta family murdered by a criminal known as the Misfit on their way to a Florida vacation. The story pays much attention to the banal details of the family’s existence: the bickering children, the irritable father, the bland mother, and the manipulative grandmother, whose unreliable memories lead to the final disaster. Underneath the ordinary surfaces of modern life, O’Connor suggests, is a real and menacing evil that can intrude without warning.

In “Good Country People” evil appears in the form of a Bible salesman. The main character, Hulga, an amputee with a Ph.D. in philosophy, decides to seduce the salesman to show him the truth about life’s meaninglessness. He instead opens his hollowed-out Bible, shows her pornographic pictures, steals her wooden leg, and leaves her trapped in a hayloft.

In “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” a tramp marries a girl with an intellectual disability in order to steal her mother’s car. After abandoning the girl at a roadside diner, he picks up a boy who has run away from home and tries to talk him into returning to his family by telling his own story, “My mother was a angel of Gawd. . . . He took her from heaven and giver to me and I left her.” The boy retorts, “My old woman is a flea bag and yours is a stinking pole cat.” The story ends with the tramp’s prayer, “Break forth and wash the slime from this earth!” Many of O’Connor’s stories end with similar redemptive moments; “Revelation” is an example.

O’Connor slowly and arduously wrote the nine stories of Everything That Rises Must Converge during the final years of her illness. In comparison with those in her first volume, they are darker in tone and more directly contend with contemporary issues. In the title story a young man named Julian, recently graduated from college, wants to embarrass his old-fashioned mother by forming friendships with Black people. He wants to force her to accept the reality of the modern world and abandon her romantic illusions, yet he is caught up in his own illusions—he wants to be a writer but sells typewriters instead, and he lives with his mother, rather than making his own way. The story’s setting and central symbol is a public bus, an emblem of the civil rights movement through its association with the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955-56 and the Freedom Riders of 1961. When Julian accompanies his mother on the bus to the local “Y,” their encounter with several Black passengers leads to a crisis that reveals his essential hollowness. The story ridicules Julian’s intellectual pretensions and his lack of compassion for his mother. This final moment of self-discovery is reminiscent of the epiphany used by James Joyce in his short-story collection Dubliners (1914).

Legacy

When O’Connor died in 1964, she left unpublished three other short stories, along with an unfinished novel. Her portraiture of characters, her evocation of mystery, her descriptions of the regional culture of the modern South, and her trenchant humor imbue her stories with a unique distinctiveness. Her view of the modern world is bleak. Many of her characters suffer terrible fates. What she offers as consolation is the possibility of spiritual redemption that lies at the heart of her view of the world: in a letter to a friend, she referred to this philosophical position as “Christian realism.” The nineteen stories in her two volumes of short fiction make her one of the most highly regarded writers of short fiction in the twentieth century.