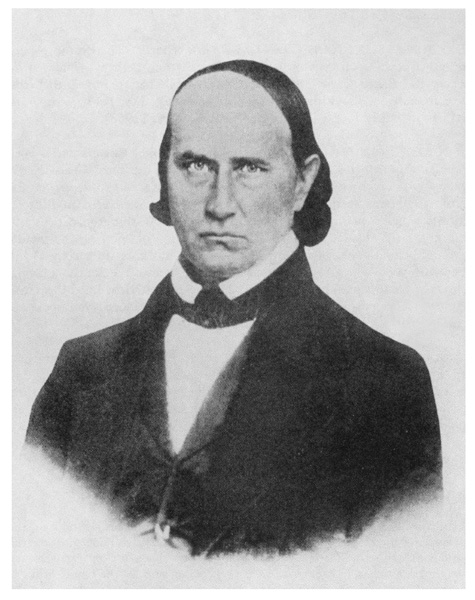

Thomas Holley Chivers, poet and physician, published eleven volumes of poetry, plays, and pamphlets. He also contributed to leading antebellum literary periodicals and newspapers, especially the Georgia Citizen, and wrote a biography of Edgar Allan Poe, his friend and kindred spirit.

Nevertheless, the eccentric Georgia writer never achieved the critical acclaim that he craved. Unfortunately, his famous legacy—the Poe-Chivers plagiarism controversy—has overshadowed his talent as a mystical poet.

Born and reared near Washington, Georgia, Chivers left Wilkes County after a failed youthful marriage. In 1830 he earned a medical degree from Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, but rarely practiced medicine. With his inheritance he was free to write, travel, live intermittently in the Northeast, and pay to publish his books. In the early 1830s he traveled widely throughout the western frontier and the North.

Before his 1835 return to Georgia, Chivers published The Path of Sorrow, mostly autobiographical poems, and Conrad and Eudora, a play about a notorious Kentucky murder trial. The title poem of Nacoochee (1837) celebrates a Cherokee legend. In 1837 Chivers married Harriette Hunt; of their seven children, four died in youth. In The Lost Pleiad (1845) the grieving father eulogizes his beloved daughter Allegra Florence (1839-42), the eldest of his children with Harriette and the first to die. His most memorable poetry appeared in Eonchs of Ruby (1851) and Virginalia (1853).

His traditional Baptist heritage notwithstanding, the tormented romantic visionary embraced the beliefs of the Transcendentalists and Swedenborgians, the latter based on a Swedish mystic’s writings on spiritualism and immortality. The deep but troubled friendship between Chivers and Edgar Allan Poe was founded on a mutual fascination with metaphysical speculations, as well as on shared literary interests. The close association between the two poets, however, ended in bitterness when each began to regard the other’s artistic borrowings as plagiarism.

Convinced that he was a divinely inspired poet, Chivers passionately devoted his life to composing musical, euphonious verse. An innovative experimenter, he excelled in capturing the rhythms and dialect of songs by enslaved people. A number of his poems and plays also reflect his ideaized views of American Indians and their plight, inspired in part by his contacts with Cherokees during his frontier travels.

Chivers spent his last years in Decatur, where he died on December 19, 1858, and is buried.