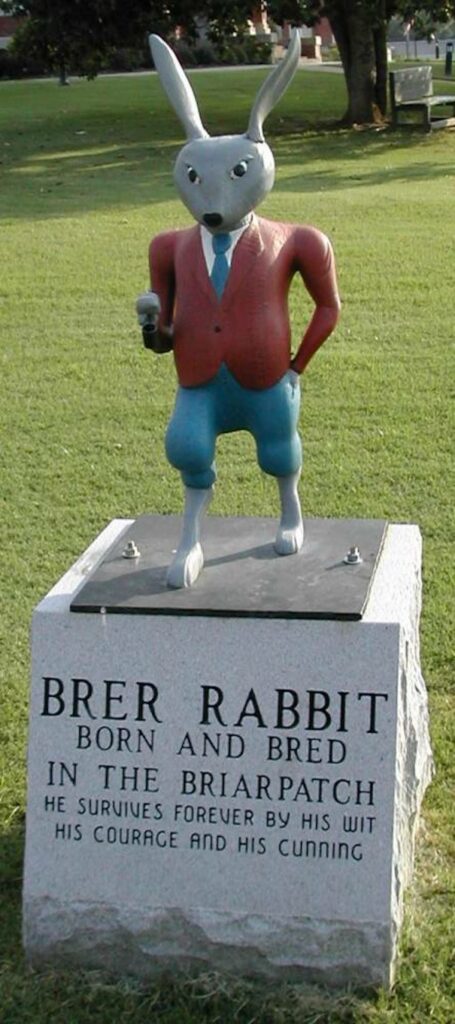

The Uncle Remus tales are African American trickster stories about the exploits of Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, and other “creeturs” that were recreated in Black regional dialect by Joel Chandler Harris. Harris, a native of Eatonton, was a literary comedian, New South journalist, amateur folklorist, southern local-color writer, and children’s author.

Origins and Influences

Two-thirds of Harris’s celebrated trickster tales—which constitute the largest gathering of African American folktales published in the nineteenth century—derive their deep structures and primary motifs from African folktales that were brought to the New World and then retold and elaborated upon by enslaved African Americans living in the southeastern United States. The remaining stories have their roots in European and Native American folklore.

The Brer Rabbit stories have been translated into nearly thirty foreign languages and have had an impressively wide influence on writers and on popular culture generally. Writers indebted to Harris include Mark Twain, Charles Chesnutt, Zora Neale Hurston, Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, and Van Dyke Parks and Julius Lester (who have retold the Uncle Remus tales in richly illustrated multivolume sets). Eatonton’s other famous literary personality, however, Alice Walker, only begrudgingly acknowledges Harris’s influence, arguing that he in effect stole a major part of the Black folk legacy from its authentic African American creators.

A whole gallery of children’s-story heroes, including Kim’s animal friends in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Books, Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit, Howard Garis’s Uncle Wiggily, and A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, were influenced by Harris’s creation of street-smart, recognizably human animal characters who speak “de same ez folks.” Walt Disney’s pioneering film that first combined live action and animation, Song of the South (1946), Disney World’s Splash Mountain theme ride, an endless array of Saturday morning cartoon tricksters, from Bugs Bunny to the Road Runner, and even B&G Foods’ Brer Rabbit Molasses were born, bred, or otherwise cooked up in Brer Rabbit’s briar patch.

The Brer Rabbit Stories

Harris’s fictionalized storyteller, Uncle Remus, was a “human syndicate” whom he had admittedly “walloped together” from several Black storytellers he had met while working from 1862 to 1866 as a printing compositor on Joseph Addison Turner’s Turnwold Plantation, outside Eatonton, in Putnam County. Although Uncle Remus’s name has its ultimate origins in Rome’s Romulus and Remus legend, its more immediate antecedent was an elderly Black gardener Harris met in Forsyth, Georgia, where Harris had served from 1867 to 1870 as an editor for the Monroe Advertiser.

From 1876 to 1879, during the first phase of Harris’s quarter-century career as associate editor of the Atlanta Constitution, he wrote for the newspaper several dialect sketches that portrayed Uncle Remus as a reluctant city dweller who was fond of dropping by the paper’s editorial office and sharing comic, philosophical, and sometimes cynical perspectives about city life in what he sometimes called “Atlanta-Ma-Tantrum.” The fact was that Remus’s heart, like Harris’s, was really back in Putnam County.

When Uncle Remus began telling Brer Rabbit tales in rural Black dialect, the stories proved to be so popular that they soon outgrew the confines of the Constitution. In 1880 Harris published a volume of these folktales, together with old plantation songs, pithy sayings, and Remus’s Atlanta street-sketches, as Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings. Harris would gather six more volumes of Uncle Remus stories during his lifetime, including, in 1895, a revised edition of his first book, illustrated by A. B. Frost. Two more volumes would appear posthumously, followed in 1955 by The Complete Tales of Uncle Remus, a collection of all 185 tales edited by Richard Chase.

Uncle Remus and His Listener

Harris embedded the animal folktales he retold in a rhetorically complex narrative frame featuring Uncle Remus and his listener, a little white boy who is the son of the plantation owner. In Harris’s second volume, Nights with Uncle Remus (1883), three other Black narrators also tell folktales: Aunt Tempy, the uppity and privileged cook in the Big House; 'Tildy, the often impertinent house maid; and Daddy Jack, a sagacious old Gullah from the Sea Islands who performs stories complexly counterpointed with musical themes. Uncle Remus himself proves, however, to be the most fully developed and gifted vernacular storyteller of the group. Remus’s character gradually evolves in the later story collections, even as his young white listener grows up and marries, eventually sending his son to learn at the knee of the seemingly ageless old man, as he himself had done a generation earlier.

The Rhetoric and Sociology of the Tales

On one narrative level Uncle Remus appears to be telling only entertaining, harmless slapstick animal tales, drawn nostalgically from the pre–Civil War Old South plantation tradition, that typically highlight the stupidity of the physically stronger animals. In the introduction to his first volume of Uncle Remus tales, however, Harris acknowledges the allegorical significance of the stories he was retelling. Clearly, Brer Rabbit is the enslaved African American’s alter ego and trickster-hero, and the so-called stronger animals represent the white enslavers. On deeper rhetorical, symbolical, and archetypal levels, Uncle Remus’s role is to initiate his young white listener into the complex realities of adult life. Yet at the same time, Uncle Remus has been educating entire generations of readers—young and old, and of all races—about the destructive power plays and status struggles among members of the animal kingdom, who clearly represent socially and ethnically different, jealous, contentious, and even openly warring members of the human race itself. The survival strategy that the tricky old shaman counsels, furthermore, is first and foremost to use one’s “thinkin’ masheen,” which almost invariably proves to be a more powerful weapon than brute strength.

Uncle Remus is an accomplished role-player and trickster himself. While humorously and affectionately telling the little boy superficially entertaining tales, he is also narrating double-stories that explore, just below the surface, a violent, predatory world of interracial strife, interclass warfare, and assaults on the human spirit itself. As Uncle Remus once stops to explain, “with unusual emphasis,” to the little white boy and to Remus’s fellow African American raconteurs, 'Tildy, Aunt Tempy, and Daddy Jack, “ef deze yer tales wuz des fun, fun, fun, en giggle, giggle, giggle, I let you know I’d a-done drapt um long ago.” Uncle Remus challenges all of his readers and listeners, in his time and our time, to read the complex book of life more compassionately and to find some kind of common ground and common humanity beyond slavery—and beyond terror and violence in any form.