Willie Lee Perryman, who performed during his career as “Piano Red” and as “Dr. Feelgood,” was a self-taught pianist who played in the barrelhouse blues style. (The term barrelhouse was used to describe a loud percussive type of blues piano suitable for noisy bars or taverns.) His performing and recording careers emerged during the period of transition between completely segregated “race music” and “rhythm and blues,” which was marketed to white audiences. Some music historians credit Perryman’s 1950 recording “Rocking With Red” for the popularization of the term rock and roll in Atlanta.

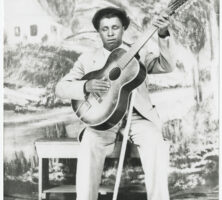

Photograph from booklet "Piano Red, Dr. Feelgood," by Norbert Hess

Perryman was born on October 19, 1911, on a farm where his parents, Ada and Henry Perryman, sharecropped near Hampton. He was part of a large family, though sources differ on exactly how many brothers and sisters he had. Perryman was an albino African American, as was his older brother Rufus, who also had a blues piano career as “Speckled Red.”

When Perryman was six years old, his father gave up farming and moved the family to Atlanta to work in a factory. Not much is known about Perryman’s education or early life, but he recalled that his mother bought a piano for her two albino sons. Both brothers had very poor vision, an effect of their albinism, so neither took formal music lessons, but they developed their barrelhouse style through playing by ear. Perryman sometimes recalled imitating Rufus’s style after watching him play, but it is doubtful that his brother was a major influence. Rufus, nineteen years older than Perryman, left Georgia in 1925 and did not return until a 1960 visit. Another influence that Perryman cited in interviews was Fats Waller, whose records his mother brought home. Other influences were likely the local blues pianists playing at “house” or “rent” parties, which were common community fund-raisers of that era.

By the early 1930s, Perryman was playing at house parties, juke joints, and barrelhouses in Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee. He developed his percussive playing style and harsh singing style to compensate for the lack of sound systems and to overcome the noise of people talking in venues. He worked these circuits with other Georgia bluesmen, including Barbecue Bob, Charlie Hicks, Curley Weaver, and “Blind Willie” McTell.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Perryman married in the early 1930s, and he and his wife, Flora, had two daughters. He obtained seasonal employment performing in Brevard, North Carolina, a mountain resort town, and he commuted back and forth between there and Atlanta. The Brevard job brought him before white audiences; by 1934 he had also begun to play at white clubs in Atlanta. In Atlanta he would play at a white club until midnight and then head over to an African American club, where he would play until 4 a.m. Perryman developed a repertoire of pop standards, which were more popular among the white audiences, while continuing his blues sets in the African American clubs.

Because of the popularity of blues on the radio, recording companies sent agents, looking for talent to sign and record, throughout the South on “field trips” from the 1920s until the mid-1930s. In 1936 W. R. Calaway, a representative for Vocalion Records, recorded Perryman with Blind Willie McTell, the famous twelve-string blues guitarist, during a session in Augusta. According to Perryman, these recordings were never released because the wax masters melted in the Georgia heat. Perryman recalled that Calaway was familiar with Rufus’s career, and knowing that Rufus’s nickname was Speckled Red, he suggested that Perryman record as “Piano Red.”

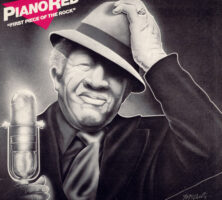

Print by Mike McCarty. Courtesy of Lowery Group

Perryman’s first marriage ended in divorce, and in 1941 he married Carrie Lou Bailey; their marriage lasted until her death in 1979. He took a job at a furniture factory, assisting upholsterers and also cleaning up. Later, Perryman learned to upholster for himself, and he maintained this job as a way of supporting his family throughout the rest of the 1940s.

In 1950 he recorded “Rockin’ with Red” and “Red’s Boogie” at the WGST radio studios in Atlanta for RCA Victor. Both songs became national hits, reaching number five and number four respectively on Billboard’s R&B chart. These initial hits, and a third single, “The Wrong YoYo,” enabled Perryman to resume a more active performing schedule. He entertained in white and Black clubs in Atlanta and was hired to perform at college parties around the Southeast. He also recorded sessions in New York City and Nashville, Tennessee, during the early 1950s.

By 1955 Perryman was also working as a disc jockey on WGST, where he was hired by Zenas Sears, who actively encouraged the marketing of African American music to white radio audiences in Georgia. Sears later bought another radio station, which he named WAOK, and he hired Perryman to be a disc jockey there as well. This association continued for thirteen years, during which time Perryman would broadcast from a small recording studio set up by the two men in the backyard of Perryman’s home. Perryman could not drive because of his poor eyesight, and working from home saved him taxi and bus fare.

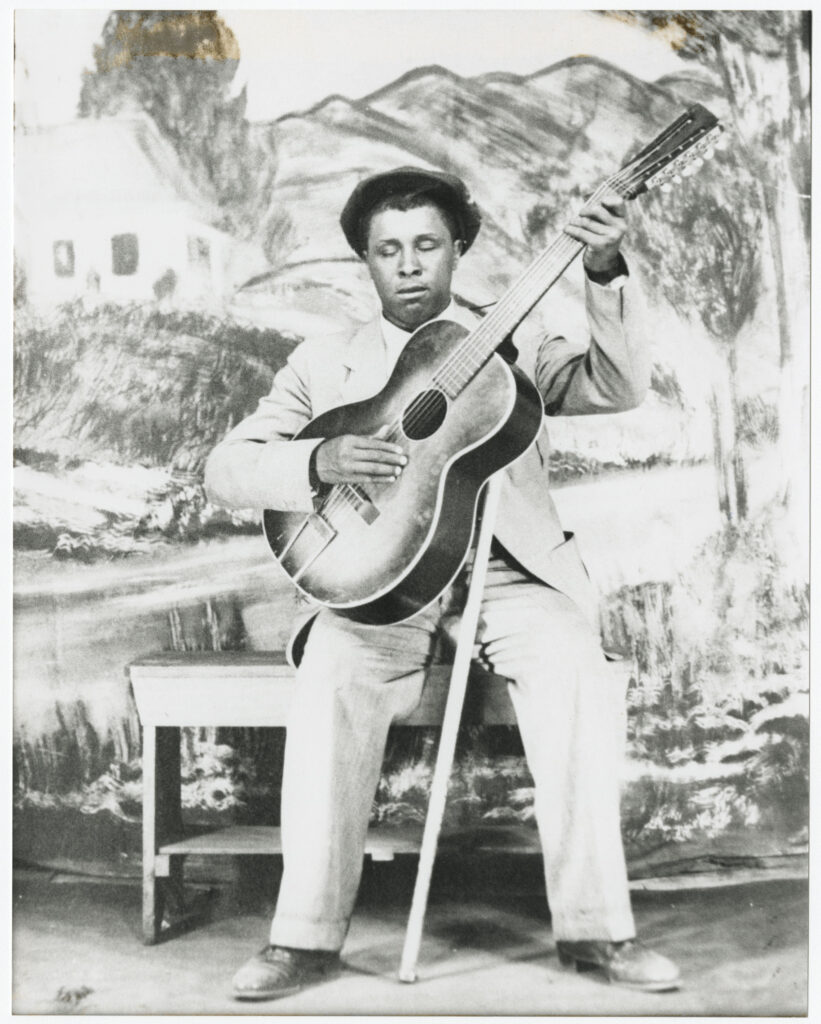

Photograph from booklet "Piano Red, Dr. Feelgood," by Norbert Hess

By the early 1960s Perryman began to appear and promote himself as “Dr. Feelgood.” This persona initially began when his band performed dressed as doctors and nurses. It also tied into the persona he adopted on his WAOK radio shows, during which he would pretend to guzzle beer between selections, promising that the drink would produce music that would make the audience feel good. Ironically, Perryman never drank alcohol or smoked cigarettes throughout his life but claimed that he drew his spirits from the universe.

As musical styles changed during the 1960s, Perryman’s repertoire did not adapt. From the mid-1950s until the late 1960s, he recorded for several companies, including Columbia, for which he made several records. However, Perryman did not make the money from this arrangement that he had been promised. He continued touring and performing at colleges in addition to doing upholstery jobs. In 1969 he began a ten-year stint as the house musician for Muhlenbrink’s saloon, an establishment at Underground Atlanta.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Perryman’s work was again highlighted, as followers of roots music began to call attention to performers of barrelhouse blues. European music business personnel sponsored a European tour, during which he played at an inauguration party for German chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Bill Lowery’s Southern Tracks studio released an album, The First Piece of the Rock, to honor Perryman’s contributions. In 1983 he was inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame and was the recipient of the Mary Tallent pioneer award.

Perryman died in 1985 after an extended struggle with cancer. He is buried in Dawn Memorial Gardens Cemetery in Atlanta.