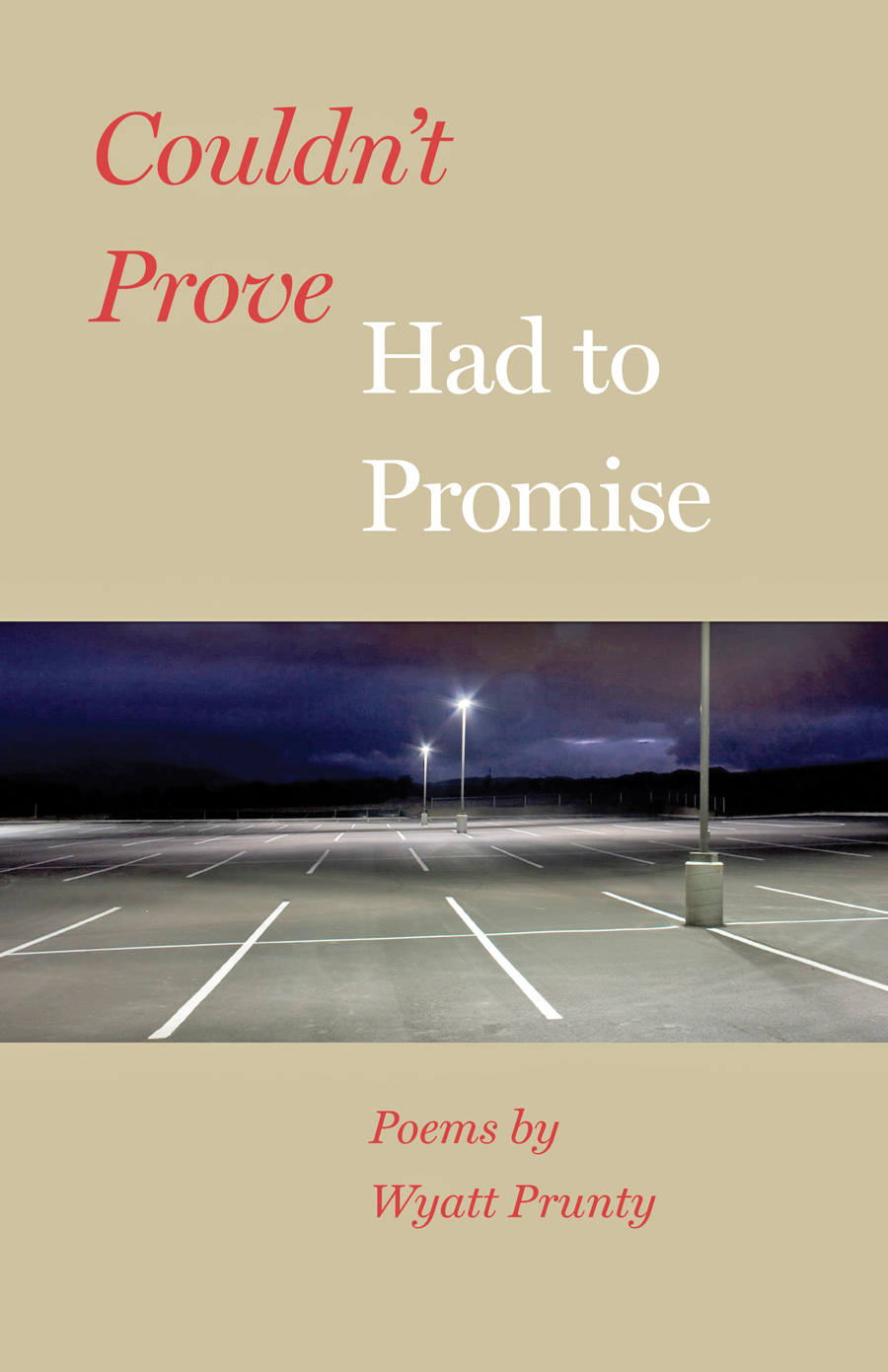

Wyatt Prunty is identified with a widely based movement among poets sometimes called the New Formalism. Such poets use form (verse and meter) and narrative as a way of exploring and expressing meaning. Prunty does not restrict his poetry to preestablished forms but employs control and order as liberating means of expression. He writes about domestic subjects—his parents, family, personal experiences, and modern life. He is the author of six collections of poetry and one book of criticism and is a frequent reviewer or essayist for poetry and literary journals.

Early Life and Career

Eugene Wyatt Prunty was born on May 15, 1947, in Humboldt, Tennessee, the son of Eugenia Wyatt and Merle Prunty. His family moved early in his life to Athens, where his father organized the Department of Geography at the University of Georgia. He received his undergraduate education at the University of the South (B.A., 1969) in Sewanee, Tennessee, where Allen Tate was one of his teachers, and where his first poems were published in the Sewanee Review under the editorship of Andrew Lytle. After three years in the navy, Prunty enrolled in the Johns Hopkins University writing seminars in Baltimore, Maryland, and received his M.A. in 1973. He earned his Ph.D.from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and counted among his mentors there Donald Stanford and Lewis P. Simpson. He has taught at Louisiana State University, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, and since 1989, the University of the South, where he is Ogden D. Carlton Chair of English and director of the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, one of the most successful annual events of its type in the nation.

Style and Themes

Writing in the New York Times Book Review, Melanie Rehak has observed that Prunty has devoted his career to “examining the ways in which human experience is made up of small traditions bound together into a larger story—the subset of ritual within narrative.” Certain themes in Prunty’s work are prominent: family life, the connection between past and present, the capricious and inexplicable nature of events, and the link between human action and the outer world. In writing about personal experience and family, as he often does, Prunty is not engaged in self-scrutiny but instead is seeking to connect with a larger set of meanings.

The range of Prunty’s poetry in form and subject is impressive. His impulse is usually narrative and ultimately philosophical. His poem “A Winter’s Tale” speculates on the birth of his son, which signifies the completion of a cycle of death and resurrection:

Ian, your birth was my close land

Turned green, the stone rolled back for leaving,

My father dead and you returned.

His poem “Blood” meditates on the rhythmic participation of human life in an ancient process. It does so in a way that is characteristic of Prunty’s approach to a subject: he begins with the literal nature of a subject, in this case the fact that the circulation of blood sustains human life:

… it runs between

The spent asphyxiated blues

Of time and work andthat bright filigree

Through which the impounding heart pumps back

Our reddened and ventilated lives.

Blood brings oxygen to the body and keeps it alive. Having established this, the poem moves to symbolic and metaphoric properties:

Scripted in a secret and minute hand

That writes itself and signs its origins

In unrepeated blues and reds

The blood holds to its systole and diastole.

Blood, in this regard, is a link to our ancient origins, both in fact and in metaphor (“bloodline”). It staves off death, as long as it circulates, and is the stuff of our life and mortality: “Blood surfaces our dust, and something more, / The potent changing earth of us.”

Prunty’s longer narrative poems are especially impressive. In “The Depression, the War, and Gypsy Rose Lee” he muses over a photograph of his parents taken in 1938, before their children were born. The photo becomes a symbol of the mystery and uncertainty of life. The poet sees in the picture the history of everything that followed the momentit preserved, yet he knows also that the young faces in the picture suspect nothing of their future:

Locked arms to pose a photograph

Surviving all these two survived

No hint of what they saw ahead

Making them smile.

“Haying” describes a young boy helping farmers gather hay. The poem is reminiscent of the work of poet Robert Frost, in such poems as “Out, Out” and “After Apple Picking,” but while Frost usually drives toward a clearly enunciated theme, Prunty allows events to speak for themselves, without mediation. The boy finds the work difficult, but he persists and at the end of the day feels elated about what he has done. He stumbles across a nest of yellow jackets and is stung. The men take care of him, waiting for the doctor, apparently unconcerned, and the boy listens to their talk:

Lie there, boy,

And listen to their neutral voices—

Used for selecting seed, planting, calving,

Used when wringing necks or cutting calves to steers,

Used for harvest, slaughter, funerals, drought—

And August always turns to drought,

One baking gust that cures the grass

Like a breath inhaled and held

So long that light turns colors.

In some narratives Prunty more aggressively questions the meaning of events: “Falling through the Ice” describes how people tell and retell the story of a boy who drowns in a frozen pond. They do so:

Because it pulls us back again

This side of what no man

Has ever laddered over with a name…

A riddle, a story, a children’s game.

They know the event signifies something about human life, its capricious unpredictability; they are fascinated by their own powerlessness to understand or explain. It is this interest and fascination with life’s mystery, the question of what lies beneath or above it all, that Prunty searches for in his poetry.

Prunty’s poetry collections include The Times Between (1982), What Women Know, What Men Believe (1986), Balance as Belief (1989), The Run of the House (1993), Since the Noon Mail Stopped (1997), and Unarmed and Dangerous: New and Selected Poems (2000). His book of essays about modern poetry, Fallen from the Symboled World: Precedents for the New Formalism, was published in 1990. He has also edited or coedited several literary anthologies.