Athens, home of the University of Georgia (UGA), is located along the north Oconee River in Clarke County, in the rolling Piedmont of northeast Georgia. Athens and Clarke County combined to form a unified government in 1990. According to the 2020 U.S. census, Athens–Clarke County had a population of 96,124.

Chosen in 1801 as the site for the first chartered state university in the nation, Athens is known for its culture and diversity. Georgia’s “Classic City” has preserved many of its historic neighborhoods and landmarks, and its largely intact nineteenth-century townscape abuts the historic North Campus of UGA. Today Athens is the center for commerce and trade, health services, and cultural arts for all of northeast Georgia. The city struggles to maintain its distinctive sense of place in the face of rapid growth and development.

Early History

Athens was founded by a committee. In 1785 the state legislature made a bold step to endow a “college or seminary of learning,” thereby initiating the concept of state-supported higher education. Sixteen years later the legislature dispatched a committee of five to select a site for the university. Among them was John Milledge, a close friend of U.S. president Thomas Jefferson’s and soon to become governor of Georgia. Searching for a healthful location, the committee encountered Daniel Easley, a settler and land speculator, who owned and operated a mill on the banks of the Oconee River at Cedar Shoals. Easley showed them some property he owned on a hill high above the shoals, and it was there that the committee agreed to set the college.

Milledge purchased 633 wilderness acres from Easley for $4,000 and donated the parcel to the trustees of the university. The trustees named the place Athens after the center of classical culture in Greece. When it was incorporated in 1806, the town had seventeen families, ten frame dwellings, and four stores. The town grew adjacent to the college on land sold by the trustees to produce revenue to construct the academic buildings.

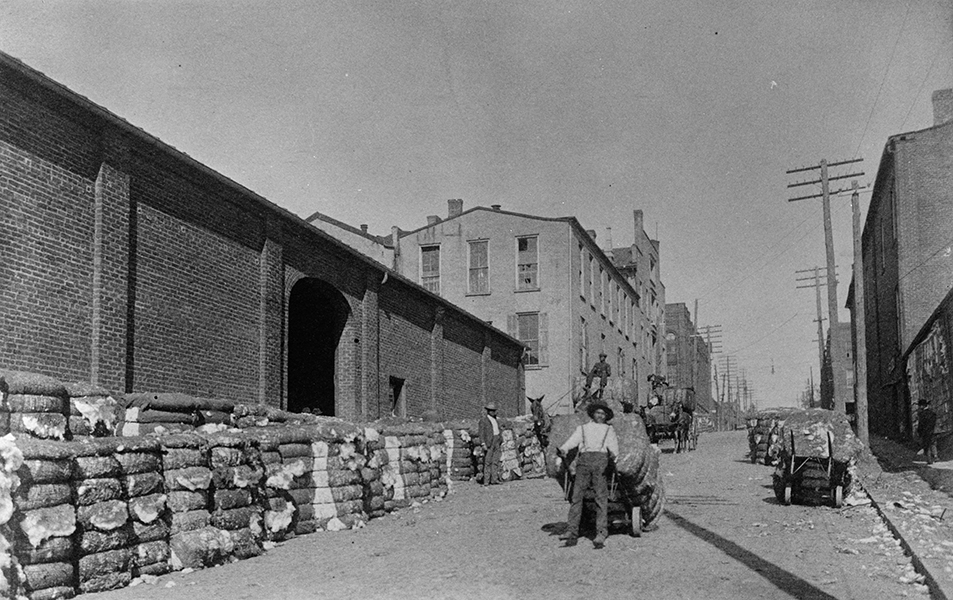

By the 1820s Athens had become a center in the South for textile manufacture, powered by the Oconee River and supplied by the vast cotton plantations nearby. Prominent residents included not only mill owners, merchants, and college professors but also the aristocrats and planters who came to Athens to educate their sons at the university and to enjoy the culture and society the college encouraged.

Many of the houses built by these antebellum Athenians still survive. For example, Ross Crane, a contractor who built the university’s Greek revival–style chapel (1832), constructed a mansion just west of the downtown area; it is now used as a fraternity house. Also on the west side of town, Robert Taylor built a Greek revival–style house with thirteen columns, one for each of the original thirteen colonies. Now known as the Taylor-Grady House, it was the boyhood home of “New South” spokesman Henry W. Grady and is designated a National Historic Landmark. John Addison Cobb, a wealthy plantation owner and enslaver who moved to Athens in 1824, created the town’s first suburb, Cobbham, in 1834. It is one of several Athens neighborhoods listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Civil War Era

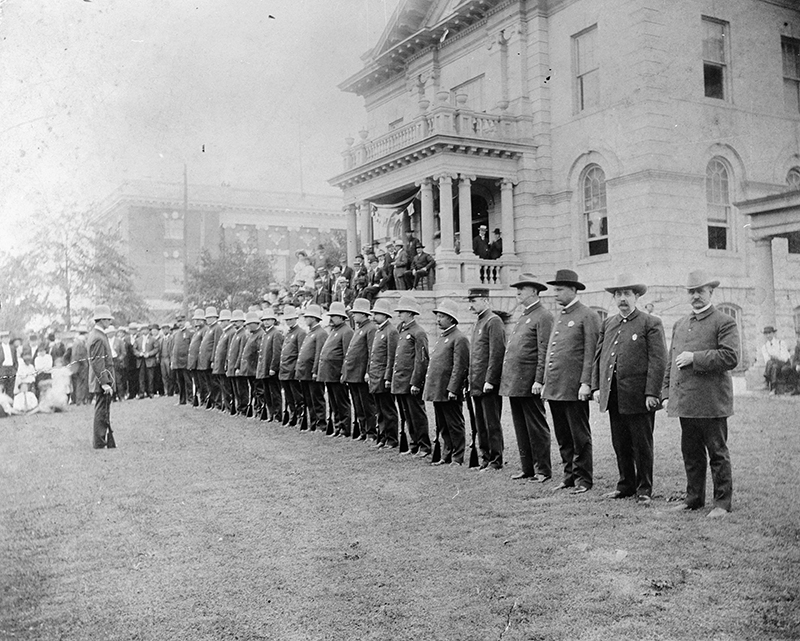

No major battles took place in Athens during the Civil War (1861-65). The only altercations were brief skirmishes at Barber’s Creek just south of town on August 2, 1864, when the Home Guard defended the town against fragments of Stoneman’s raiders, a Union cavalry force from East Tennessee that moved into the area as an extension of the Atlanta campaign.

Athens was, however, the wartime home of the Cook and Brother Armory, a converted textile factory. Cook and Brother manufactured infantry rifles (most notably the famous Enfield rifle), artillery and carbines, and the double-barreled cannon, which stands today on the grounds of city hall as the local symbol of the Lost Cause. The cannon misfired when the two balls linked by a chain failed to fire simultaneously.

By 1860 enslaved people made up nearly half the population of Clarke County. At the start of the war 1,892 enslaved people and one free African American lived in Athens. Their numbers increased during the war as enslavers allowed their enslaved workers to “hire out” to earn wages in town for the enslavers gone to battle. The armory often hired skilled enslaved workers during the war.

Athens was a major gathering point for Confederate enlistees and a haven for refugees from active theaters of war. Athens textile industries produced great quantities of Confederate uniforms, many put together by the Ladies Aid Society. When the war began university enrollment stood at 113, but in 1863, with students and faculty needed in the army, the university closed and remained so until after the war. The Confederacy requisitioned all campus buildings to house soldiers and refugees. The chapel became an army hospital and in 1864 a prison for 431 Northern soldiers taken nearby.

In the war Clarke County lost more than 300 men and boys (out of a total white male population of 2,660), and more than 100 university students and alumni perished. The most distinguished Athenian who lost his life in battle was Brigadier General Thomas R. R. Cobb, who wrote the Confederate Constitution. Cobb’s brother Howell, who survived the war, was president of the Provisional Confederate Congress and rose to the rank of major general. Active in national politics before the war, he had been Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and secretary of the treasury.

Late Nineteenth Century

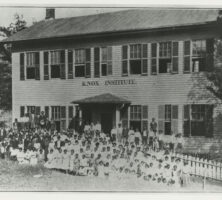

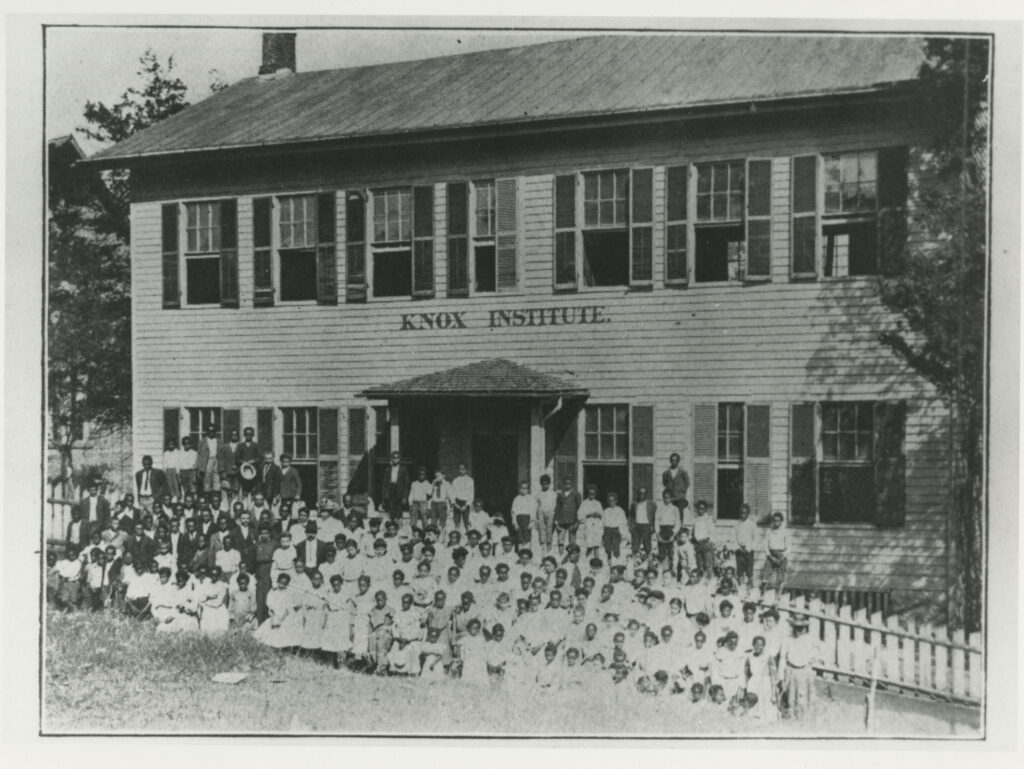

After the surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, Union troops occupied Athens from May 1865 until early 1866. Freepeople flocked to Athens to celebrate emancipation. Thanks in large measure to the Freedman’s Bureau, Athens became a center for secondary Black education in Georgia for more than fifty years following the war, and a significant Black middle class emerged. The Knox School (later renamed the Knox Institute) opened in 1868, the Methodist School in 1876, and Jeruel Academy in 1881. African American men and women attended Black colleges and returned to Athens in professional positions, establishing their own social and fraternal orders and publishing three Black newspapers.

Athens native Lucius Holsey, a young enslaved man with “an insatiable craving for some knowledge of books,” learned to read in slavery. After emancipation he became a delegate to the first organizational meeting of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (later Christian Methodist Episcopal Church), later becoming a bishop. Holsey also founded Paine College in Augusta.

During the war some prosperous Athenians placed their money in northern and European banks. Their capital, combined with wartime profits from the production of armaments and Confederate uniforms and a stockpile of cotton accumulated behind Union lines, allowed Athens to recover rather quickly from the economic hardships of war. Manufacturing and trade flourished.

In January 1866 the university reopened, and by 1868 returning veterans swelled enrollment to 299, the highest level yet. Federal dollars first came to Athens when the university became a land-grant institution in 1872, enabling the creation of the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts. As the university began to grow from a small, classical college for the elite into a larger, more varied institution serving the entire state, the town grew as well.

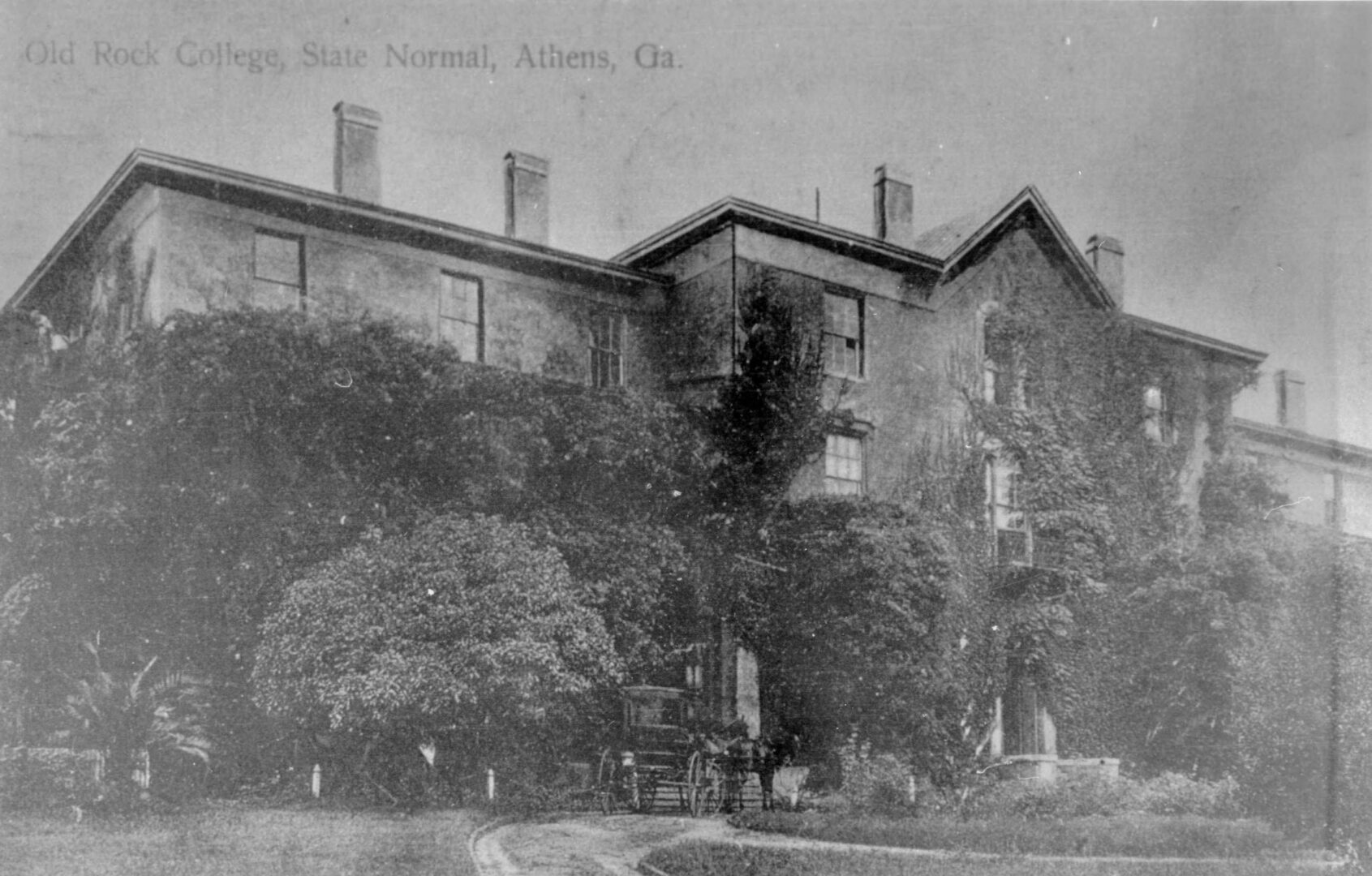

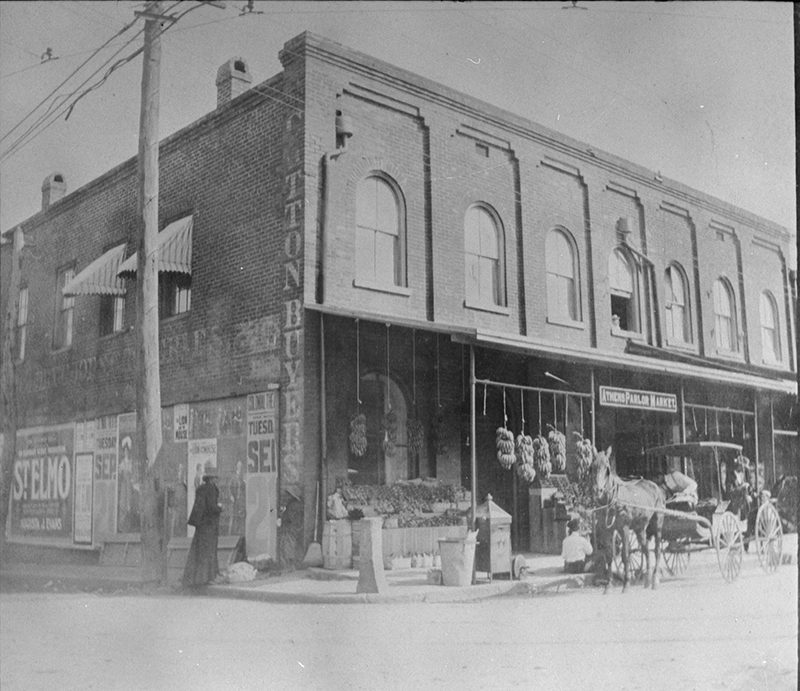

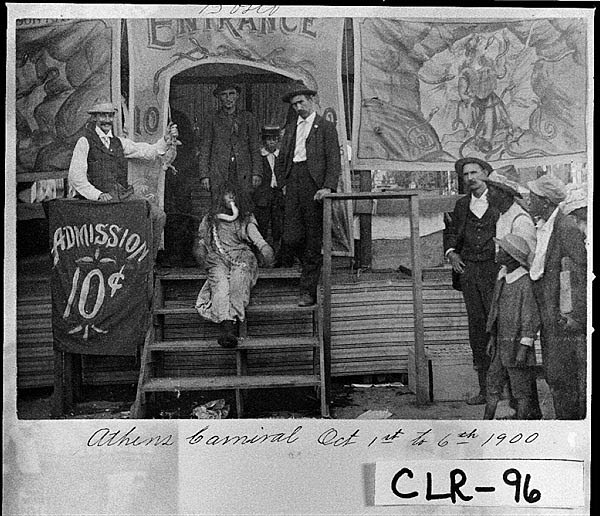

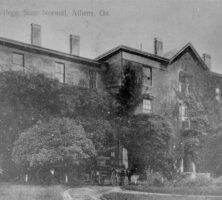

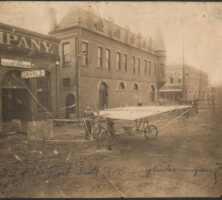

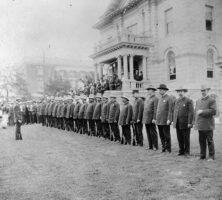

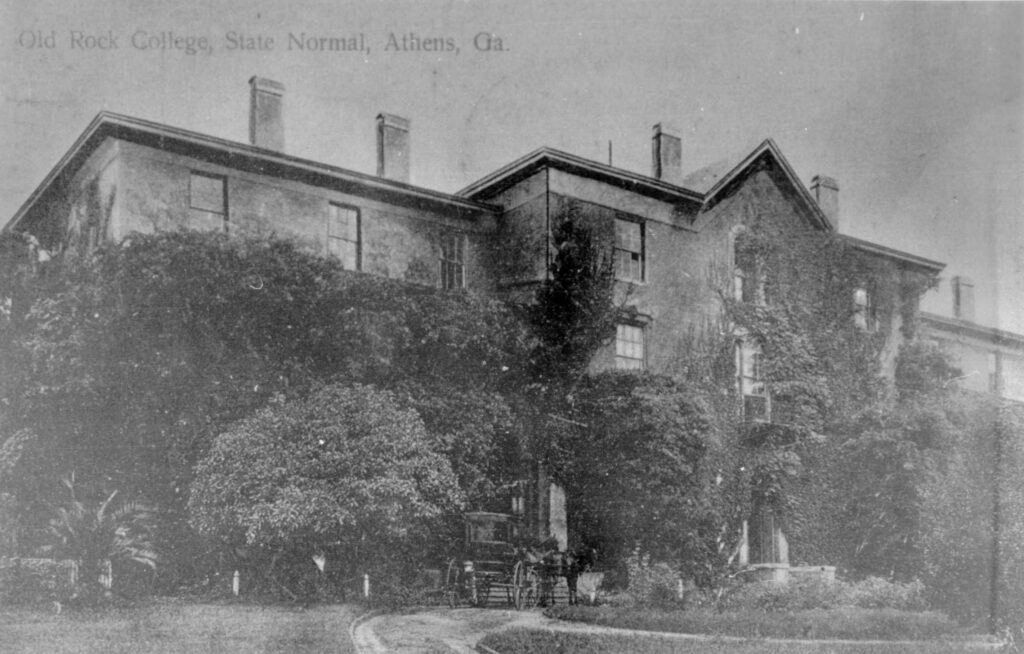

Athens became Clarke’s county seat in 1872. Passenger streetcars introduced in Athens in the 1880s led to the development of the town’s first streetcar suburbs, and the city’s population grew from 6,099 in 1880 to 10,245 in 1900. The first public schools opened in 1887 in identical ten-room brick buildings on Washington and Baxter streets—one for white students and one for Black students. The State Normal School for women opened in 1891 in a university-owned building and later moved to its own campus, in the section of Athens now known as Normaltown. The 1890s witnessed the institution of a police force, telephone service, and a modest downtown street-paving program.

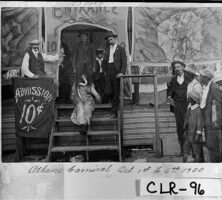

Monroe B. “Pink” Morton, a local real estate agent and politician, served as the second Black postmaster of Athens in 1897. Today the historic Morton Theatre, built by Pink Morton in 1910 at “Hot Corner” as a cultural center for the Black community, is one of only four Black vaudeville theaters remaining in the country. Morton is buried in Athens’ historic Black cemetery, Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, along with such other notable African American citizens as quilter Harriet Powers, educators Annie Smith Derricotte and Samuel F. Harris, and state legislator Madison Davis.

Twelve Athens women founded America’s first garden club in 1891 in the Cobbham home of Mrs. E. K. Lumpkin. Today the Founders’ Memorial Garden on North Campus, designed by the late Hubert Owens, founder of the UGA’s School of Environmental Design, commemorates these women.

Rapid Growth in the Twentieth Century

The early twentieth century was a prosperous era for Athenians. Merchants and bankers built new establishments downtown, and electric lights and water service spread across the townscape. When the first automobile appeared in Athens in 1899, the race for greater mobility began. The population of Athens doubled between 1900 and 1940 from 10,245 to 20,650. The Beaux-Arts city hall completed in 1904 rose atop the town’s highest point. James Knox Taylor (architect of the U.S. Treasury Building in Washington, D.C.) designed the Federal Building, which was completed the following year across from city hall. Then it housed the federal court and post office; today it is a bank. A. Ten Eyck Brown designed the county courthouse, completed in 1914. Three multistory buildings, the highest standing at nine stories, changed the Athens skyline between 1908 and 1913.

Athenian Ben Epps, a pioneer in early aviation, built his first plane shortly after his friends the Wright Brothers got off the ground in 1903. Today, Athens–Ben Epps Airport honors him.

Philanthropist George Foster Peabody endowed a new city library and generously contributed to a fund to build a World War I memorial (Memorial Hall) on campus in 1925. The prestigious Peabody Awards, honoring excellence in broadcasting, is named for him and administered by UGA.

The Athens area grew rapidly during and after World War II (1941-45), and by 1980 the population of Athens and its suburbs was 62,896. From 1951 through the 1970s outside industry moved in. Dairy Pak, Gold Kist, General Time, and Westinghouse built manufacturing plants and brought executives to Athens as Beechwood and other suburban neighborhoods emerged. A grant from the Kellogg Foundation built the Georgia Center for Continuing Education, one of the first conference centers in the nation. The Navy Supply Corps School moved in 1954 from Bayonne, New Jersey, to the old State Normal School campus and remained there until 2010. (The UGA Health Sciences Campus opened on the site in 2012.) In 1958 the Athens Area Vocational-Technical School (later Athens Technical College) first opened its doors in former army barracks located downtown. The university, which had swelled with returning veterans after World War II, also benefited from the coming of age of the postwar baby boom generation, reaching an enrollment of 23,470 in 1980.

Recent Developments

In 1980 Athens became a Main Street City, one of the first in the state to embrace a program for downtown revitalization through the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Thanks to Historic Athens (formerly the Athens-Clarke Heritage Foundation), the National Register of Historic Places lists the entire downtown as a historic district. In 2006 the Athens–Clarke County Commission designated most of the city’s downtown a historic district, instituting new guidelines for the construction and renovation of buildings within that area.

Following consolidation of the city and county governments in 1990, preservationists won a long battle to save and incorporate an old firehall into the $27.3 million Classic Center. The facility combines convention space and a theater for the performing arts. At the entrance a statue of Athena, the Greek goddess of war and the personification of wisdom, commemorates the 1996 Olympics, when Athens hosted women’s soccer, rhythmic gymnastics, and volleyball competitions.

Georgia’s Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax (SPLOST) is proving a useful tool to Athens–Clarke County, funding restorations, schools, a new library, bike paths, nature trails, public utilities, and more. The university’s sophisticated Performing Arts Center complements the Classic Center, and the Georgia Museum of Art brings the world of art to town and gown. The 313-acre State Botanical Garden of Georgia serves as headquarters for the Garden Club of Georgia and offers nature trails, gardens, a conservatory, and a chapel. The North Oconee River Greenway Project is developing a thirteen-mile trail for bikers and hikers.

R.E.M. and the B-52’s put Athens on the map in the 1980s as a lively venue for rock music and helped spawn a plethora of bands and the clubs where they perform. The B-52’s left Athens, but R.E.M. stayed to make their mark as historic homeowners, preservationists, and friends of the environment as well.

Athens has its own symphony, opera company, band, choral societies, gospel groups, folk, jazz, blues, and more. In the spring, the annual Human Rights Festival brings together political activists, musicians, and craftsmen, and the city’s Twilight Criterium, one of the country’s largest cycling events, attracts both cyclists and spectators. Athfest, a local music festival held on outdoor stages and in venues around town, takes place each June, and on autumn weekends the town swells as football fans flock to watch the University of Georgia Bulldogs.

UGA is the largest employer in Athens–Clarke County, and its presence is still the largest single factor in the city’s increasingly diversified economy. Major industries in Athens–Clarke County include poultry and timber.