The boll weevil greatly affected Georgia’s long history of cotton production between 1915, when the insect was introduced to Georgia, and the early 1990s, when it was eliminated as an economic pest. Yield losses associated with the boll weevil reduced cotton acreage from a historical high of 5.2 million acres during 1914 to 2.6 million acres in 1923. Although insecticides provided temporary relief, the cotton industry remained unprofitable, and planted acreage continued to decline, to a low of 115,000 acres in 1983. The boll weevil’s decimation of the cotton industry in the South had implications for the entire region. The pest was a driving force behind the great migration of poor tenant farmers into northern cities, and the state’s dependence on cash-crop production left its soil depleted and prone to erosion.

In 1987 Georgia growers began participating in a program to eradicate the boll weevil. Over a period of years the program proved successful, and Georgia producers have increased cotton acreage and yields significantly while reducing their dependence on insecticides.

The adult boll weevil measures from three to eight millimeters from the tip of the snout to the abdomen, which is half the length of its body. Its color is usually reddish or grayish brown but may vary according to age and size. A distinctive characteristic is the double-toothed spur on the inner surface of each front leg. A newly hatched larva is inconspicuous, and the mature larva is white, legless, and about thirteen millimeters long. Larvae complete development in cotton fruiting structures. The primary damage to cotton occurs when female boll weevils deposit eggs in fruiting structures (e.g., flower buds, squares, seed pods, or bolls) on developing cotton plants. Upon hatching, the boll weevil larvae or grubs feed in the square, causing it to be shed by the plant or rendering the bolls unsuitable for harvest.

Before eradication the boll weevil was the chief pest of cotton in Georgia as well as in other areas of the cotton belt. Indeed, the boll weevil was such an economic pest that it engendered an unprecedented amount of research and pesticide application. In 1972 it was estimated that one-third of all pesticides in the United States was applied to cotton for boll weevil prevention.

Photograph from the Agricultural Research Service

Intensive use of broad-spectrum insecticides for boll-weevil control, such as calcium arsenate and DDT, often caused outbreaks of other insect pests because these insecticides cause the destruction of natural enemies that suppress various pest species in cotton, such as parasites and predatory insects. Fields that used broad-spectrum insecticides often had a loss in yield similar to that in fields that did not use broad-spectrum insecticides. The term “pesticide treadmill” was coined in the early 1970s to describe this cycle as it relates to the boll weevil: pesticides were developed and overapplied, the population of natural predators that were not targeted by the pesticide increased, and then new pesticides were developed and overapplied. This cycle both harmed the environment and did little to reduce crop loss. Additional hurdles to the boll weevil’s eradication included the boll weevil’s reproductive resilience. Studies found that even if 90 percent of a boll weevil population was treated in a given area, then the remaining population could still reproduce and reinfest the surrounding area after only four generations, which takes less time than a typical growing season.

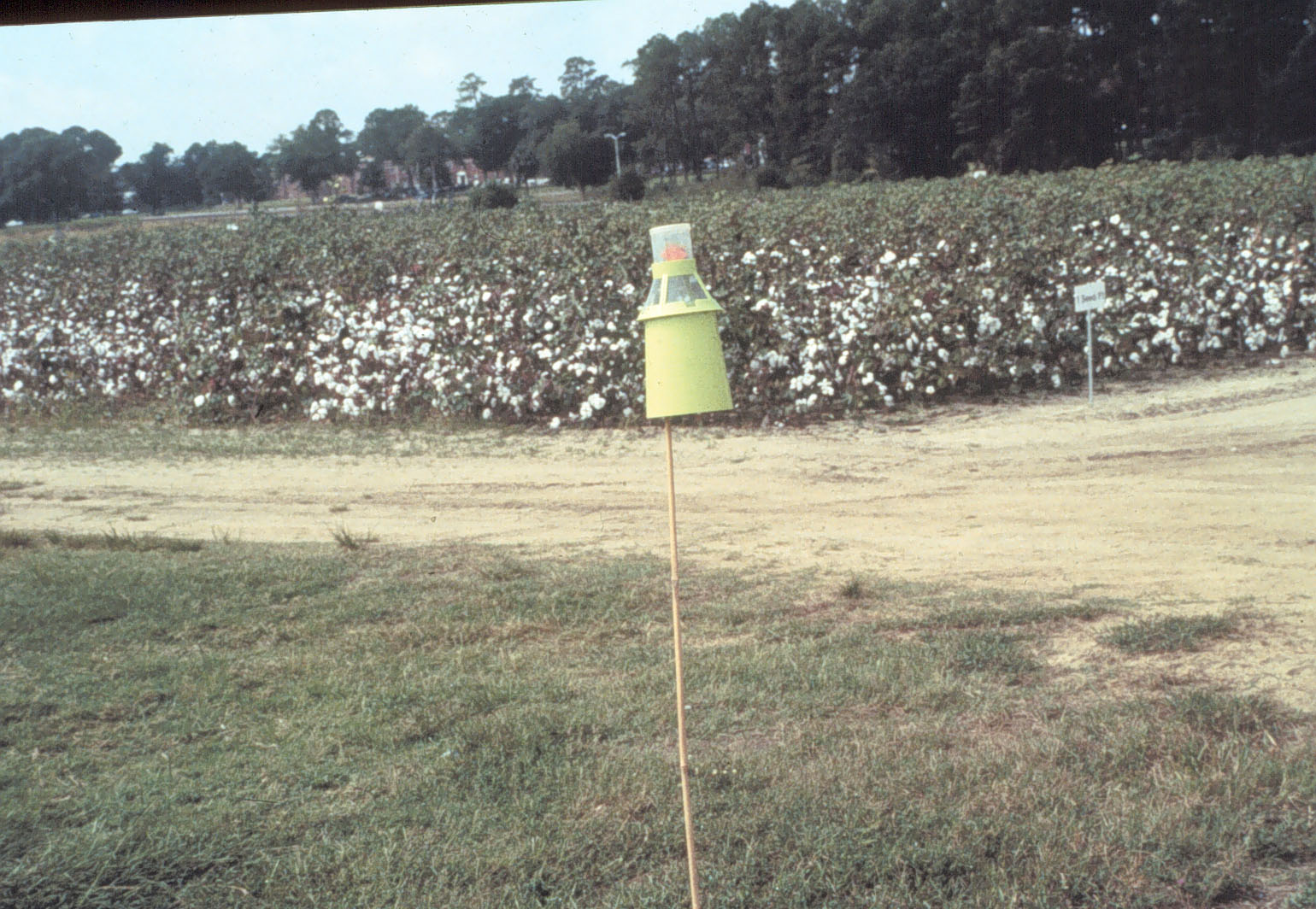

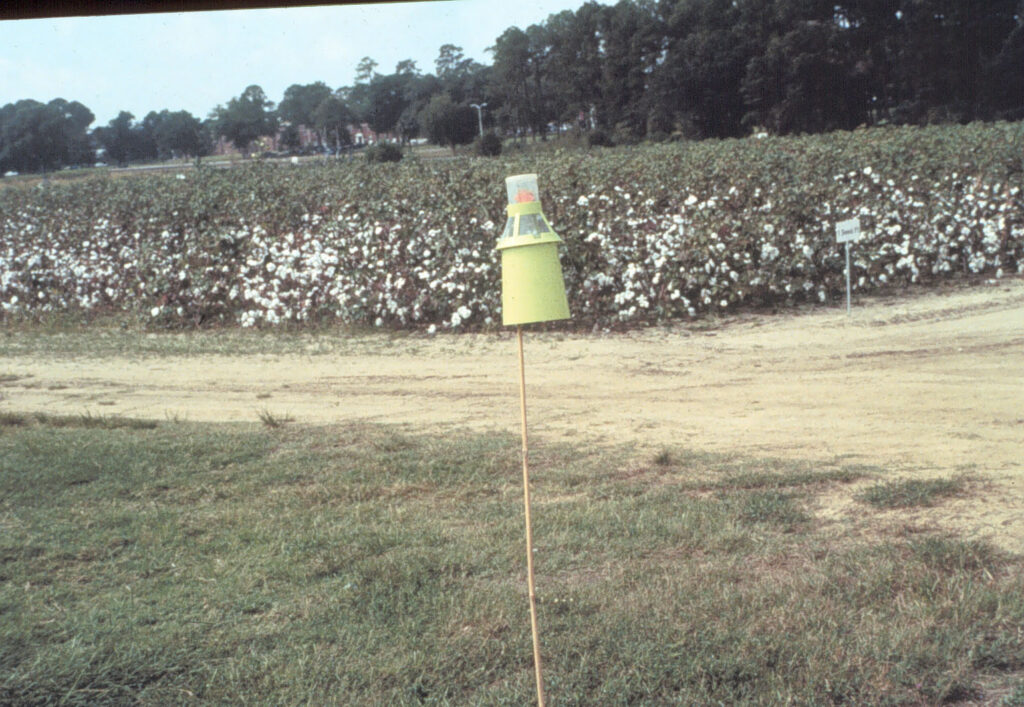

Several biological factors made it possible to eliminate the boll weevil. The ability to mass-produce boll weevil pheromones in 1972 and the development of advanced boll weevil traps were integral parts of boll weevil eradication. These traps were useful because they allowed farmers to limit the number of boll weevils on their land and because they allowed farmers to detect small populations of boll weevils before they ballooned into a large infestation

Courtesy of Phillip Roberts

Cultural practices for boll-weevil management, or non-insecticide means of reducing risk or avoiding particular insect infestations, include early planting, stimulating rapid plant growth and development with appropriate fertility and weed-management programs, and using early-maturing varieties. In addition to the use of such cultural practices as stalk destruction after harvest, which eliminated plant hosts for reproduction, infested fields were treated with the insecticide malathion. All cotton growers in Georgia are required to participate in the Boll Weevil Eradication Program (BWEP).

Since elimination of the boll weevil as an economic pest, insecticide use in cotton has been reduced by approximately 75 percent, and yield losses associated with insects have been reduced by 50 percent. Today the eradication of the boll weevil is considered one of the world’s best examples of “integrated pest management,” which is the reduction of agricultural pests through means that are minimally damaging to the environment.

The most damaging and frequent insect pests that Georgia growers encounter today are bollworm and tobacco budworm (both caterpillar pests that feed on squares and bolls). Others include the cotton aphid, beet armyworm, cutworm, fall armyworm, tarnished plant bug, cotton fleahopper, soybean looper, stink bugs, thrips, and whiteflies. Modern Georgia cotton producers continue to take an integrated approach to insect management, using such natural controls as predatory bugs to suppress pest populations. Insecticides remain a critical component of insect-management programs but are used only on an as-needed basis on in-field pest populations.

The BWEP is an ongoing program, as boll-weevil reinfestation continues to be a threat to the cotton industry. Boll weevils have been eradicated in most of the country, but they still plague parts of Texas. Cotton growers pay an annual assessment on each acre of cotton planted to monitor for and eliminate reinfestations if they occur. Boll weevil traps can be commonly observed on the perimeter of Georgia cotton fields during late summer and early fall. For the Georgia cotton industry, the BWEP has been a tremendous success from both an environmental and an economic perspective. Though Georgia’s cotton yield has not yet surpassed the highs seen before the boll weevil infestation, Georgians increased cotton yields ten times over between 1982 and 2012. Georgia farmers planted around 131,000 acres of cotton in 1982 and nearly 1.3 million acres in 2012.