Begun in 1928 in Louisiana as the Delta Air Service, the Atlanta-based Delta Air Lines is, as of 2015, the world’s largest in terms of passengers, with operations around the world.

Through sound management it survived a competitive airline market in the 1930s; in the postwar era it modernized and expanded its fleet, gaining new service routes beyond the South through approval by the Civil Aeronautics Board and by corporate acquisitions. In the modern era of deregulation, which has seen the downfall of such historic carriers as Pan American (or Pan Am), Eastern Air Lines, and TWA, Delta Air Lines has prospered and grown. Indeed, Delta’s growth paralleled, and helped fuel, the growth of Atlanta as a regional and national commercial center. The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., combined with a slowdown in the U.S. economy, have imposed new challenges on the domestic airline industry, including Delta.

Beginnings

Delta’s origins can be traced to a historic decision by B. R. Coad and C. E. Woolman. Coad was an employee of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s field laboratory in Tallulah, Louisiana; Woolman was with its extension service. They worked on finding a solution to the boll weevil infestation of cotton crops and concluded that the “dusting” of an insecticide powder from the air would be the most effective form of treatment. Born from this decision was Huff Daland Dusters, Incorporated, a crop-dusting operation begun in Macon in 1924 and moved to Monroe, Louisiana, in 1925. Woolman left his position with the extension service and in the off-season traveled with the company to Peru, where he helped to establish crop-dusting and passenger services. With this experience Woolman returned to the United States and in 1928 raised the capital to buy Huff Daland, renaming it Delta Air Service, with headquarters in Monroe. The name Delta, referring to the Mississippi River region, was suggested by Catherine Fitzgerald, a secretary who later would rise to the rank of an executive in the company.

Woolman purchased three Travel Air six-seat monoplanes and on June 17, 1929, inaugurated Delta’s passenger service from Love Field in Dallas, Texas, to Jackson, Mississippi. Later in the year, service to Birmingham, Alabama, and Meridian, Mississippi, was added. In 1930 the Delta Air Corporation (as it was then called) expanded eastward to include service to Atlanta, the fastest-growing city in the South, and westward to Fort Worth, Texas. Delta’s lack of success in winning a commercial airmail contract—the bread and butter of any aspiring air service—jeopardized its early existence, however, and the company was forced to suspend passenger service.

Reprinted by permission of Delta Air Lines

A reprieve came for Delta on the heels of the “airmail scandal,” when the U.S. Congress enacted the Air Mail Act of 1934. Woolman secured a low-bid contract for the new Route 24 airmail service between Dallas and Charleston, South Carolina, via Atlanta. That same year Delta resumed passenger services, flying Stinson Trimotors. From a precarious beginning it now had a foothold in the Deep South, with Georgia’s capital city, Atlanta, as the prize.

Market Competition and the Civil Aeronautics Board

With the exception of the “Big Four” airlines (Eastern, TWA, United, American) that were favored with mail contracts and routes, the aviation industry in the 1930s was less a business than a high-stakes gamble. Safety remained a constant concern. An important step in regulation was the passage of the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938, which created the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). The legislation was typical of U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s second term, favoring business stabilization, growth, and safety within a competitive market. Delta was an early beneficiary and by 1943 obtained CAB approval to expand its route system to Cincinnati, Ohio, to the north, Savannah to the east, and New Orleans, Louisiana, to the south. In the meantime, Delta upgraded its fleet to include Douglas DC-2s and DC-3s, and in 1940 added flight attendants to the flight crews. These aircraft established standards of reliability, safety, and passenger comfort; they also signaled the company’s policy of staying technologically competitive. With its headquarters in Atlanta since 1941, Delta was becoming an established southern-based carrier in the national air system.

The War Years and After

America’s entry into World War II (1941-45) slowed Delta’s growth. With fewer aircraft in operation, Delta converted its Atlanta facility and personnel into aviation maintenance and training cogs in the national war effort. In 1945 the company’s official name became Delta Air Lines, and Woolman, Delta’s first vice president, became president and general manager.

In the decade after the peace of 1945, Delta stayed current with technology advances by purchasing new equipment and seeking new routes. In 1945 the CAB approved a Chicago–Miami, Florida, route via Atlanta—Delta’s second foray outside the South. In 1948 the company began flying the all-new Douglas DC-6, a pressurized, four-engine passenger plane that cruised at 328 miles per hour. The company next purchased the impressive DC-7 and replaced its DC-3 aircraft with Convair 440s. Delta also benefited from “interchange service” agreements with TWA, National Airlines, and American Airlines, which allowed Delta crews to carry passengers to and from airports in Michigan, Florida, and California. Under Woolman’s guidance, Delta gained a reputation as a well-managed, competitive line that carefully but ambitiously paced its expansion outside the region. It was also winning employee loyalty by Woolman’s “people-oriented” approach.

Reprinted by permission of Delta Air Lines

Delta Expansion

While the CAB brought stability to the industry, trends in mergers and consolidation continued. The most significant up to this point took place in 1953, when Delta merged with Chicago and Southern Airlines (C&S), giving it access to a Great Lakes route system in the upper Midwest and, importantly, to points in the Caribbean Sea served by C&S.

Even more significant, in 1955 Delta obtained approval to operate an Atlanta to New York route. Scheduled service extended to Philadelphia; Baltimore, Maryland; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Delta celebrated New York as an especially sweet corporate victory, for it symbolized national commercial visibility for itself, its home base of Atlanta, and the region it served. It was also in 1955 that Delta introduced the “hub and spoke” system of connecting flights, which is now used by most of the major airlines in operation. (A hub is a central airport that flights are routed through, and spokes are the routes that planes take out of the hub airport.)

Its streak of fortune continued in 1961 with CAB approval to operate in its own right (as opposed to interchange service) from points in California and Florida. Two years later, Delta’s continuing foray into international markets received CAB approval for an interchange agreement with Pan Am that allowed Delta aircraft to fly from Atlanta and New Orleans to points in Europe. Delta’s second National Safety Award (the first council award was in 1945) added to the company’s reputation.

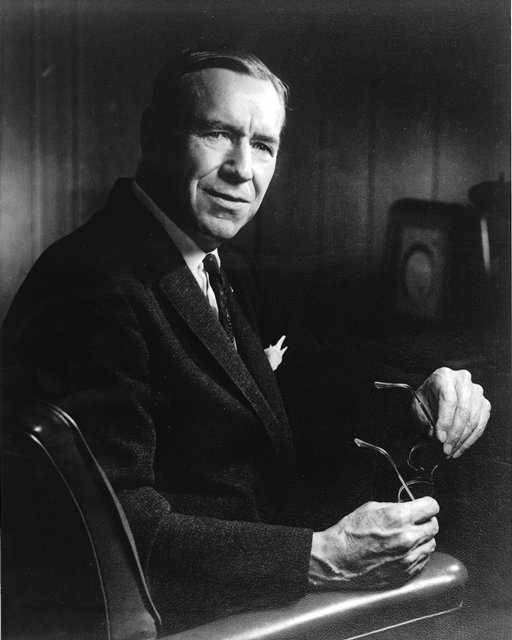

When Woolman died in 1966, the company lost the leader who had dominated the airline from the start and stamped it with his personality. Successor chief executive officers over the next two decades were Charles H. Dolson (1965-70), W. T. Beebe (1970-71), and David Garrett (1971-87).

Transition to Jets

The Deep South propeller airline that Woolman had first envisioned was becoming a modern jet service with international reach. Delta took a leap with the purchase of the new Douglas DC-8 jet that entered service in 1959. A representation of the jet’s graceful swept wing, a new red, white, and blue triangle logo (the “widget”) began appearing on Delta’s aircraft. Its fleet grew with the addition in 1960 of swift Convair 880s (they set a coast-to-coast record of just over three hours) and in 1965, the DC-9. When Delta became an all-jet airline in 1970, its inventory of new equipment economically—and with engineering advantage—accommodated the airline’s diversifying market, from short-haul to international flights.

Reprinted by permission of Delta Air Lines

Delta carried out its second merger in 1972 with the acquisition of Northeast Air. Though a troubled airline, Northeast offered an attractive prize to a national carrier with its Boston base and routes to Canada, Bermuda, the Bahamas, and Miami, Florida. Delta chose to keep the airline’s Boeing 727s. While it retained a cost-conscious, practical business approach emphasizing service—one highly identified with its home base—Delta now was operating on a vaster scale.

The Wide-Body Jet Era and the L-1011

In 1970 Delta entered the wide-body era with the purchase of the first of five Boeing 747s. The wide-body jet could carry more passengers farther, and at a cheaper overall cost. Delta followed with the purchase of a limited number of Douglas DC-10s, a stopgap until its larger order of the new Lockheed L-1011 TriStars could be delivered. (The order had been delayed because of problems in the development of the TriStar’s Rolls Royce engines.) In 1973 the TriStar entered service for Delta. Because of its favorable economics and advanced systems, the L-1011, fifty-four in all, became the mainstay of Delta’s wide-body fleet. The TriStar was the plane that supported Delta’s expansion in domestic, transcontinental, and international markets. Eventually it was replaced by the Boeing 767-300ER and the MD-11 on the international routes, and in 2001 by the Boeing 767-400ER for domestic routes.

The Modern Era: Deregulation

In 1978 Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act, phasing out the CAB’s route and rate authority. Though not in favor of this far-reaching legislation that would change the face of the industry, Delta acted on the opportunities it presented. That same year it began transatlantic service to London, England, with the L-1011, adding flights to Frankfurt, Germany, in 1979 and Hawaii in 1984. In August 1979 Delta set a monthly passenger boarding record in Atlanta. In 1984 the company established its Delta Connections partnership linking local “feeder” airlines that served mid-size population areas to Delta nodes. While deregulation invited entrepreneurial risk-taking that shook up traditional patterns of corporate dominance (and led some airlines to ruin), Delta chose a cautious though deliberate growth plan.

Photograph from Wikimedia

Commercial aviation’s greatest challenge in its earliest years was convincing an interested but skeptical public that flying was safe. Delta’s enviable record played a role in winning public acceptance. In the mid-1980s, however, the company faced setbacks when a Delta TriStar crashed on its final approach to Dallas. Safety examiners determined that the cause of the crash was wind shear accompanying stormy conditions. On four occasions over a three-week period in 1987, Delta aircraft incidents involving human errors kept the airline in the news, though none of these incidents resulted in injury. A crash of a Delta 727 on takeoff from Dallas in 1988 because of an improper flap setting did result in loss of life. Delta responded to these accidents and errors with a complete review of its training programs and operations and made improvements.

A Global Airline

Delta started its first transpacific service to Tokyo, Japan, from Portland, Oregon, on March 2, 1987. The following month, Delta’s third acquisition took place with the merger of Western Airlines. Western’s Salt Lake City, Utah, base brought access to the West, Mexico, and Canada and made Delta the fourth largest national and fifth largest international passenger airline. It also added to the company’s growing fleet of Boeing aircraft (the 737, 757, and 767). Delta’s relationship with Douglas continued with the purchase of the McDonnell Douglas MD-88, a descendent of the DC-9, and the wide-body MD-11 for its new Pacific route. That year Ronald W. Allen became CEO and chairman.

Reprinted by permission of Delta Air Lines

In 1991 Delta’s international market reached a new level with its record-setting acquisition of Pan Am’s transatlantic routes (Pan Am was in liquidation). In 1993 Delta established a code-sharing arrangement among other airlines, giving the company access to more destinations. In 1995 the company added scheduled service aboard its new wide-body MD-90 and two years later began service to Latin America. In 1997 Delta set a record for passenger boarding volume, and Leo Mullin was named president. In 1999 the company added the Boeing 777 to its fleet. By the turn of the century, Delta Air Lines had become a true global carrier—an extraordinary progress from three six-seat monoplanes and a few pilots serving four Deep South cities in 1929. As of mid-2004 Delta had access to more than 494 cities in 86 countries.

Challenges in the Twenty-first Century

The challenges of operating an airline have remained essentially the same since the mid-1930s: viability depends upon safety, equipment, economy, market, and service. The new feature is deregulation, the results of which are still playing out to tremendous effect as airfares plunge. Revisions in bankruptcy law, by allowing new low-service, low-fare competitors to reorganize and stay in the market after a business failure, has made profitability even more of a challenge for the major carriers. The job of running an airline was never easy. The airline business is a capital-intensive industry that now must make do in an unpredictable world. In addition to fare competition, such cyclical developments as inflation, recession, labor actions, and fuel prices are some of the variables in a company’s survival or defeat. Shutdowns, consolidations, and mergers have become common: the downfall of historical giants including Pan Am, Eastern, and TWA, and the precarious perch of such others as American and United represent a new chapter in airline history. Behind them, however, are new airlines (some short-lived) promising low-cost, no-frills fares to an ever-wider public.

Reprinted by permission of Delta Air Lines

For the major airlines, the situation has only worsened with the downturn in the U.S. economy and the decline in air travel since September 2001. Because it has climbed to the top, Delta’s newest challenge is one of managing a multibillion-dollar global business in a competitive environment riddled with political and international stress. Delta posted a $2.4 billion loss in 2001-2.

In early 2003 Delta created Song, a new unit of the company that offers flyers competitive low-fare amenities. In November 2003 CEO Mullin abruptly announced his retirement, a decision that followed a controversial move to give bonuses and pension guarantees to some executives (for which he subsequently apologized). He was replaced by Gerald Grinstein, a longtime member of Delta’s corporate board and the former CEO of Western Airlines.

Delta posted a fourth-quarter loss for 2004 of $2.2 billion, the largest loss in a single quarter in its history. As a stopgap measure, Grinstein successfully negotiated a giveback by the pilots of about one third of their pay and benefits, and he obtained new financing. New efficiencies were added, including reducing airplane turnaround time at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, lowering fares in some markets to be more competitive with low-cost air carriers, and instituting fuel-conservation measures. The company also sold some of its jets and cut thousands of jobs. The rapid escalation of fuel prices in the summer of 2005 pushed Delta’s total losses since 2001 to $10 billion.

After employing numerous strategies to reduce costs, increase revenues, and turn around staggering losses, the company finally filed for bankruptcy protection from creditors on September 14, 2005. (Northwestern Airlines, the fourth-largest carrier in the nation, also filed for bankruptcy the same day.) The following month Delta announced the closure of Song. The airline emerged from bankruptcy on April 25, 2007, and resumed public trading of its shares on the New York Stock Exchange about a week later.

Delta has a history of sound management and profitability. Its survival in the 1930s in the shadow of the Big Four was a mark of Woolman’s business savvy and practical sense. Its lead in the purchase of Douglas jets, its aggressiveness in acquiring market assets, its responsiveness to issues of safety, its pride in service, its avoidance of labor wars, and its global expansion kept Delta competitive in the postwar era and elevated it to become the nation’s third largest airline in 2003.

Despite the difficulty that much of the industry finds itself in—and the continuing challenge of operating in a deregulated environment—its home base at Hartsfield in Atlanta and in the southern region continue to mark Delta’s destiny.