The gold-covered capitol dome in the Atlanta skyline signifies that the city is home to Georgia’s state government. That would seem to make sense, as Atlanta is the largest and best-known city in the state, but interestingly, the size of a city has nothing to do with its designation as a state capital. Of Georgia’s five contiguous states, only in South Carolina does the largest city serve as capital. In fact, in only seventeen states is the state capital also the largest city.

Courtesy of Georgia Info, Digital Library of Georgia.

Georgia has had five different state capitals. Almost every state has moved its state capital at least once. Only Massachusetts, Nevada, North Dakota, Vermont, Washington, and Wyoming have had a single capital city since their creations as colonies, territories, or states.

Georgia’s Colonial Capital

In February 1733 James Oglethorpe and the first Georgia colonists landed at Yamacraw Bluff, where they laid out the new settlement of Savannah. Three months later, Oglethorpe and the Yamacraw chief Tomochichi signed a treaty, which ceded Creek lands from the Savannah to the Altamaha rivers, inland from the coast as far as the tide flowed, to the Trustees.

Savannah was not technically the colony’s “capital” or “seat of government” during this period. Official governmental power resided with the Trustees in England, whose decisions were subject to the king’s assent and approval by the Board of Trade. By virtue of their 1732 charter, the Trustees were given control of the new colony for twenty-one years, after which Georgia would become the responsibility of the British crown. Instead of designating a governor to administer the colony, the Trustees instead retained much of the control themselves.

Concern over the Spanish forces at St. Augustine in Florida led Oglethorpe to return to England and plead for a British military presence south of Savannah. In 1736 Oglethorpe returned to Georgia with the regiment and additional colonists, with whom he established a new settlement on St. Simons Island. Here, they laid out the town of Frederica (named in honor of Frederick, King George II’s eldest son) and built Fort Frederica on the island banks of the inland waterway. Oglethorpe spent the rest of his time in Georgia at Frederica (or to the south, in military campaigns against the Spanish), leading some historians to credit Frederica as Georgia’s de facto capital from 1736 to 1743, when Oglethorpe returned to England.

However, in 1737 the Trustees had designated William Stephens, who lived in Savannah, as secretary of the colony of Georgia, meaning that for the following six years, Savannah could also make a claim to the seat of government for the colony. In 1743 the confusion ended when Oglethorpe returned to England and the Trustees designated Stephens “president” of the colony of Georgia. From this point, Savannah clearly served as the center of the colony’s government (such as was authorized or allowed).

With Georgia’s transition from a trustee to a royal colony in 1754, the Board of Trade declared Savannah the “seat of government,” and thus the royal governor, new legislative assembly, and courts established headquarters there.

Georgia’s first royal governor, John Reynolds, made a tour of Georgia in 1755. He was impressed with a bluff located about fourteen miles from the mouth of the Ogeechee River. Reynolds named the site Hardwick and began a campaign to designate it the capital of the colony. Such action would require approval by the Board of Trade back in England. In his appeal to the board, Reynolds wrote, “Hardwicke has a charming situation, the winding of the river making it a peninsula; and it is the only fit place for the capital. There are many objections to this town of Savannah being so, besides its being situated at the extremity of the province, the shoalness of the river, and the great height of the land, which is very inconvenient in the loading and unloading of ships.” Twenty-seven lots were laid out at Hardwick, and 21,000 acres of nearby land were granted. Plans for a large fort were also drafted, and a few people actually settled there. However, the Board of Trade failed to fund the undertaking, and Georgia’s proposed capital never became more than a small trading town.

Two decades later, as the Revolutionary War (1775-83) approached, Savannah became the center of the movement for independence from Great Britain; during 1775 both the newly convened provincial Congress and the royal Commons House of Assembly met in Savannah. By the end of 1775, however, the royal government no longer controlled the colony.

Savannah: Georgia’s First State Capital

At the time of statehood in 1776, Georgia’s revolutionary government operated from Savannah, though no document or election formally designated Savannah as the capital city. As the largest city of the new state, and by virtue of the tradition of the past three decades, Savannah remained the seat of government. Georgia’s first state constitution—that of 1777—directed that the state legislature meet in Savannah, although it also allowed the assembly to meet at other places as it should decide.

Just after Christmas in 1778, Savannah fell to British forces. Georgia’s government fled the city and attempted to reorganize in Augusta, located 127 miles to the north. After the capture of Savannah, British and Tory sympathizers attempted to reinstitute royal government in the city. In January 1779 an attempt was made to convene the revolutionary legislature in Augusta, but representatives from only three counties were present, and thus no quorum could be assembled. A temporary governing executive council was named, but it had to flee later that month as the British arrived in Augusta. The council later returned when the British abandoned the city in February. Other attempts to organize a government in Augusta were made that year, but the revolutionary forces were split into two factions.

Finally, in January 1780, a new assembly was convened in Augusta and a resolution was passed designating Heard’s Fort—a site to the northeast in Wilkes County—as the meeting place for the legislature in case of attack. Soon the British recaptured Augusta, and Georgia’s government convened at Heard’s Fort in May 1780. This fortification, named after Stephen Heard, president of the executive council, was located eight miles from the present-day city of Washington. Heard’s Fort disappeared after the American Revolution, and no trace remains of the village that served as a temporary seat of Georgia government during the war.

Little is known about the location of Georgia’s state government over the next year. Likely, it kept on the move in Wilkes County and may even have moved into South Carolina. By April 1781, a new offensive was under way by Continental forces against the British, and Augusta was soon recaptured. An effort was again made to reassemble a state government for Georgia in Augusta, and in August a newly elected legislature was convened. This body elected a new governor and other state officials and proceeded to enact a variety of laws. Augusta served as the capital from August 17, 1781, until May 4, 1782. By this time, the tide of war had changed in favor of the American forces, and by July 1782, the British had evacuated Savannah.

As Georgia state officials prepared to return to Savannah, one other city served temporarily as the unofficial seat of government until the British evacuated. New Ebenezer, a small Salzburger settlement on the Savannah River twenty-five miles upstream from Savannah, served as the meeting site for Georgia’s House of Assembly on July 3 and 4, 1782. On July 4, the legislature also convened here but adjourned to meet in Savannah. New Ebenezer, once the center of Georgia’s hoped-for silk industry, would later fade from existence, as did Frederica and Heard’s Fort.

Savannah and Augusta as Rotating Capitals

Following the recapture of Savannah from the British, the state legislative assembly convened in the coastal city on July 13, 1782. However, a rift between coastal and upland Georgia, which had been growing before the Revolutionary War, surfaced. The increasing importance of Augusta led the executive council to spend part of the year in that city, and the capital subsequently rotated between Savannah and Augusta until 1785.

In January 1783 the General Assembly met in Savannah, but in February the council resolved to move the capital to Augusta so that it would be nearer the growing backcountry. On May 15 lawmakers attempted to convene in Augusta, but no quorum was present until July 8. Once the session began, however, it remained under way for about a month.

On January 6, 1784, the General Assembly returned to Savannah, adjourning that session in February with a motion to meet in Augusta the following July. On July 5, 1784, lawmakers attempted to convene in Augusta, but for a week no quorum could be assembled, and the members present asked the governor to call the assembly, and name a time and place, when a meeting of the legislature should become necessary.

Such a meeting was called for on October 6, 1784, in Savannah. Again a quorum could not be assembled, and the session adjourned on October 14. On January 4, 1785, another session was convened in Savannah, marking the last episode of that city’s history as the capital of Georgia. Where precisely the assembly met in Savannah is uncertain, as there was no statehouse building. The legislature likely followed the earlier example of various revolutionary assemblies, which met in taverns (including that of Peter Tondee), private homes, and perhaps other meeting halls.

Augusta: Georgia’s Second Capital

As large inland areas neighboring the coastal area of the state had been obtained from Native American groups and opened to white settlers, the center of population began shifting from Savannah and the coast. The frontier settlers discovered the convenience of the capital’s location in Augusta, for in those days, many matters handled by courts today, such as divorces and name changes, had to be enacted by the legislature. Additionally, the legislature approved land grants, bridges and ferries, pardons, excusals from paying taxes, authorizations to practice law, and a number of other things, which made living near the meeting site of the legislature important.

Thus, by 1784 there was growing concern among the new settlers that the capital would revert to Savannah. The agitation for a new capital became so great that when the General Assembly adjourned its last meeting in Savannah on February 22, 1785, it resolved that “all future meetings of the Legislature shall be and continue at that place (Augusta) until otherwise ordered by the General Assembly.”

Augusta thus became the official capital, and the first session of the legislature convened there on January 3, 1786. However, for many, Augusta was situated too far east, and on January 26, 1786, the legislature appointed a commission to find a “proper and convenient place” for a new capital—one that would be centrally located and accessible to all (white) residents of the occupied sections of Georgia.

For the 1786 session, lawmakers rented the Augusta house of Abraham Jones, which was located on the southwestern corner of Broad Street and Lincoln Street (later Third Street). Needing a larger facility, the General Assembly negotiated with the trustees of Richmond Academy for the rental of its building on the eastern corner of Lincoln Street and Elbert Street (later Fourth Street).

Louisville: Georgia’s Third Capital

The commission appointed by the legislature in 1786 to find a new site for the capital was not entirely unbridled in its task, for the legislature’s mandate also stipulated that the commission select a location within twenty miles of an Indian trading post known as Galphin’s Old Town, or Galphinton, on the Ogeechee River in what is now Jefferson County. George Galphin had established a trading post at the site two decades earlier. The commission was authorized to purchase 1,000 acres for the new capital, which would be patterned after Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the first capital of the United States. The legislature also directed that the new capital site be called Louisville in honor of Louis XVI of France, in appreciation for French assistance during the Revolutionary War.

The actual site selected for the capital was at the intersection of three roads—one leading to Savannah, one to Augusta, and one to now-forgotten Georgetown—where a market, built in 1758, still stands today. Approved plans for the new capital city called for five streets on each of the four sides of the market, with a statehouse and governor’s mansion located an equal distance on either side.

Despite the designation of the new capital city, Augusta continued to serve as the state capital for ten more years, until 1796. The building of the capital at Louisville was delayed by a lack of funds, the death of the contractor, and the rush to obtain and disburse Creek and Cherokee lands.

Finally in 1795, a special constitutional convention was held, in part to correct for land speculation during the infamous Yazoo Land Fraud. The convention members adopted a new amendment to the Constitution of 1789 that officially designated Louisville as the “permanent seat of government” and directed that the governor and other state officials be in the new capitol at Louisville before the next meeting of the legislature.

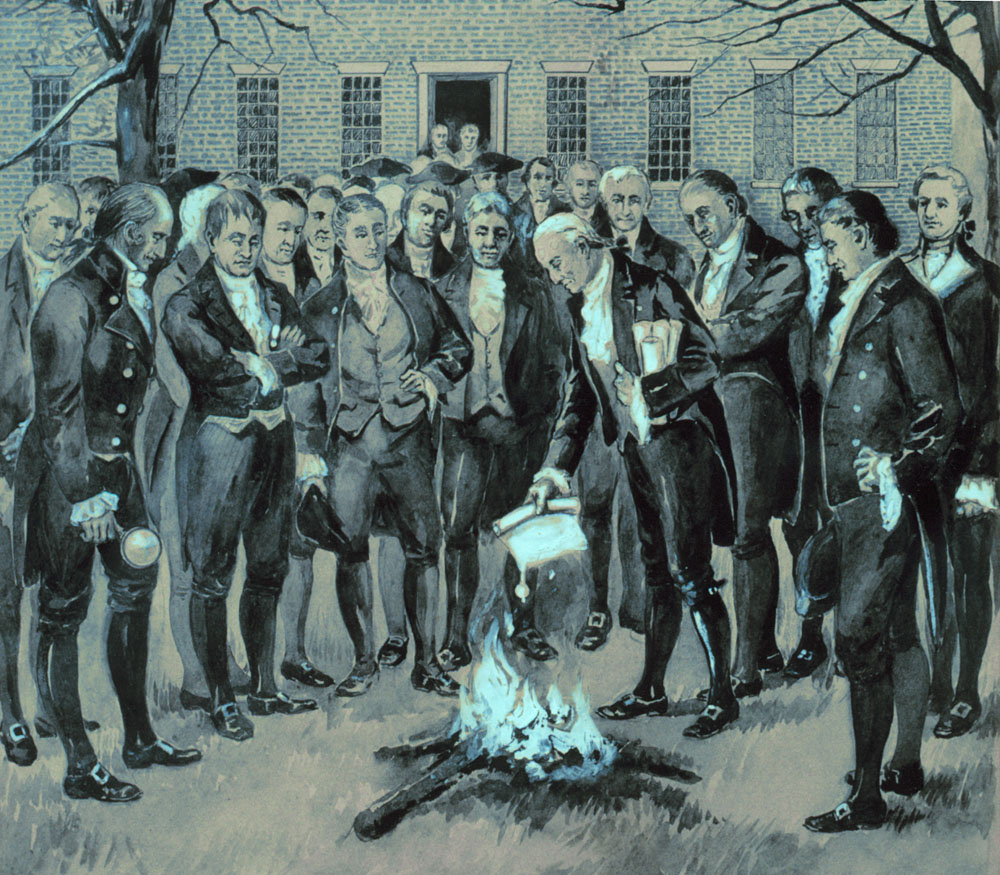

By March 1796 a new capitol building designed in the red-brick Georgian architectural style was completed, and Georgia’s state government soon occupied it. There are no known paintings or sketches of the building, except for several artists’ renderings of the burning of the Yazoo Act on the grounds of the Louisville capitol.

In a new state constitution adopted in 1798, Louisville was designated the “seat of government,” but the term “permanent,” which had been included in the previous document, was omitted. The General Assembly could now change the site of the capital by a legislative act. The press for new Indian lands continued unabated, and Louisville would serve as the Georgia state capital for only ten years. Reportedly, the desire to move the capital also arose out of a concern about malaria in the Louisville area.

In 1802 Creek lands west of Louisville were ceded to Georgia. No sooner had this territory been divided into counties than a drive to move the seat of government was again initiated. Only seven years after Louisville became the capital, the May 11, 1803, joint session of the General Assembly appointed a commission to select a site suitable for a permanent capital at the head of navigation of the Oconee River. On December 12, 1804, lawmakers passed an act to build a new capital, which would be named Milledgeville in honor of the current governor, John Milledge.

It is not known precisely when state officials left Louisville for the new capital, although it is known that the legislature at Louisville passed an act appointing the commissioners of the town of Milledgeville in December 1806.

In 1807 the legislature turned the Louisville statehouse into a public arsenal. It later served as an Irish lodge and as a county court building. Eventually the building was condemned as unsafe and torn down. The Jefferson County Courthouse now stands on the site, where a plaque marks the location of Georgia’s first capitol building.

Milledgeville: Georgia’s Fourth Capital

Some 3,240 acres were appropriated for the new capital in Milledgeville; lots were sold in the city, and the proceeds were used to construct the new statehouse. Construction of the capitol took two years, and by the fall of 1807 the building was ready for occupation, although the finishing touches would not be completed until 1811. (Over the next thirty years, two wings were added.) Government Square occupied almost twenty acres in the city. In October 1807 fifteen wagons carrying the treasury and public records of the state left Louisville for Milledgeville.

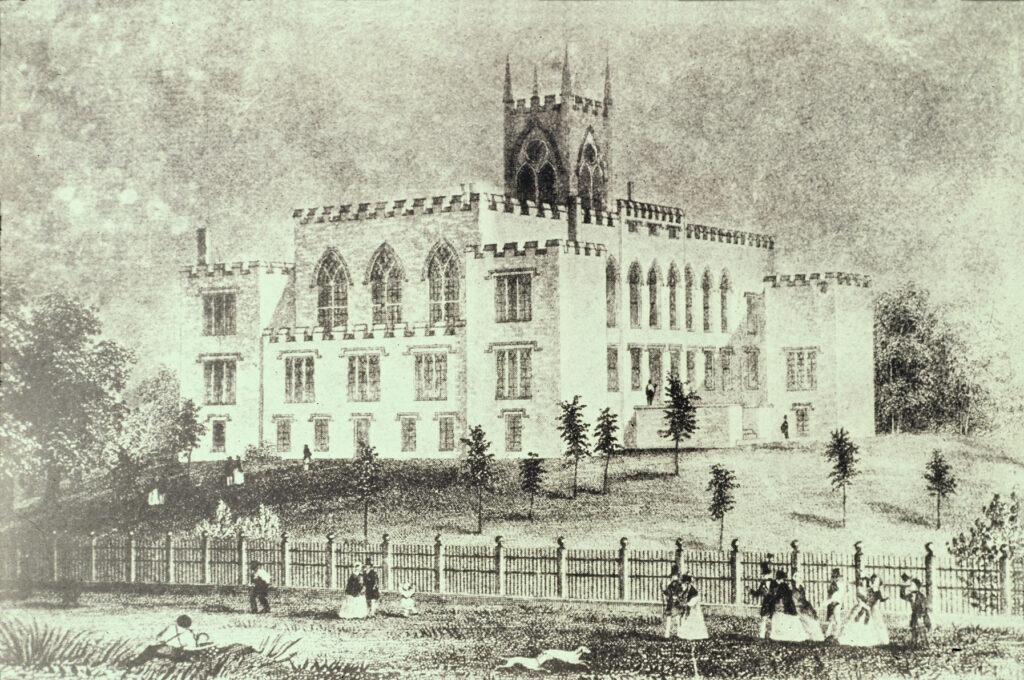

The new Gothic revival brick building, located about three-quarters of a mile from the Oconee River, was a parallelogram, with walls four feet thick. Although it was a magnificent statehouse for its time, the structure did not have the dome commonly associated with capitol buildings and resembled instead a castle or fortress.

For sixty years Milledgeville served as Georgia’s capital city. The pressure to acquire more Indian lands continued, however, particularly after the forced removal of the Cherokees from the state in 1838. Lawmakers anticipated that, once again, a desire to move the capital would soon be heard, and this time the arrival of the railroad era would play a role in the debate.

The new candidate for the capital city was a small settlement located ninety miles northwest of Milledgeville, near the Chattahoochee River in DeKalb County. The site was part of a large area ceded to Georgia by the Creeks in 1821. In December 1836, the Georgia legislature chartered the Western and Atlantic Railroad to connect the Chattahoochee and Tennessee rivers. By 1838 construction on the railroad had begun, and soon the collection of stores and shacks supplying the railroad builders from the southern end of the line was known as Terminus.

In mid-1842 Samuel Mitchell, who had donated land to the Western and Atlantic, and Charles Garnett, a chief engineer, changed the name of Terminus to Marthasville in honor of former governor Wilson Lumpkin’s youngest daughter, Martha. In December 1843 the legislature incorporated Marthasville. Some residents and workers objected to a frontier railroad town bearing such a feminine name, however, so the name Atlanta (based on the Western and Atlantic Railroad) was proposed. Despite Lumpkin’s disapproval of what he considered a slight to his daughter, the General Assembly formally approved the name change in December 1847.

Atlanta was soon to vie for consideration as the state capital, in part due to its rapid growth and its status as the rail center of Georgia. By 1845 the Georgia Railroad linked Atlanta to Augusta, and the following year the Macon and Western (later the Central of Georgia) connected Atlanta to Macon. Soon Charleston, South Carolina; Memphis, Tennessee; and other cities would link with Atlanta, prompting that city to initiate a campaign for becoming Georgia’s next capital.

The first legislative proposal to make Atlanta the capital came in December 1847, but the General Assembly defeated the measure by a 68-55 vote. Seven years later, Atlanta proponents succeeded in getting lawmakers to place the proposal before the electorate. In the 1854 general election, the statewide tally was 49,781 for staying in Milledgeville; 29,337 for moving to Atlanta; and 3,802 for moving to Macon.

Milledgeville remained Georgia’s official state capital throughout the Civil War (1861-65), though the statehouse was evacuated in November 1864 as Union general William T. Sherman approached the city. Many official state records were loaded on trains, which pulled out just before Sherman’s troops reached the city. Sherman spared the capitol from burning, but the building was ransacked by Union troops.

With Union forces in control of Milledgeville, the state government fled to various other locations. The General Assembly held a special session from February 15 through March 11, 1865, at Macon’s old city hall. In November the governor, Joseph E. Brown, fled Macon to escape Sherman’s troops on their March to the Sea. He took refuge at his plantation in Cordele but was back in Milledgeville by December.

In May 1865, following the surrender of the Confederate army to the Union, Governor Brown called the legislature to convene later that month in Milledgeville at the statehouse, but he was arrested by Union troops, and the legislature did not meet. Subsequently, Union troops took charge of state government in Georgia. A new constitution was adopted, elections were held, and in December 1865, the legislature met at the Milledgeville capitol.

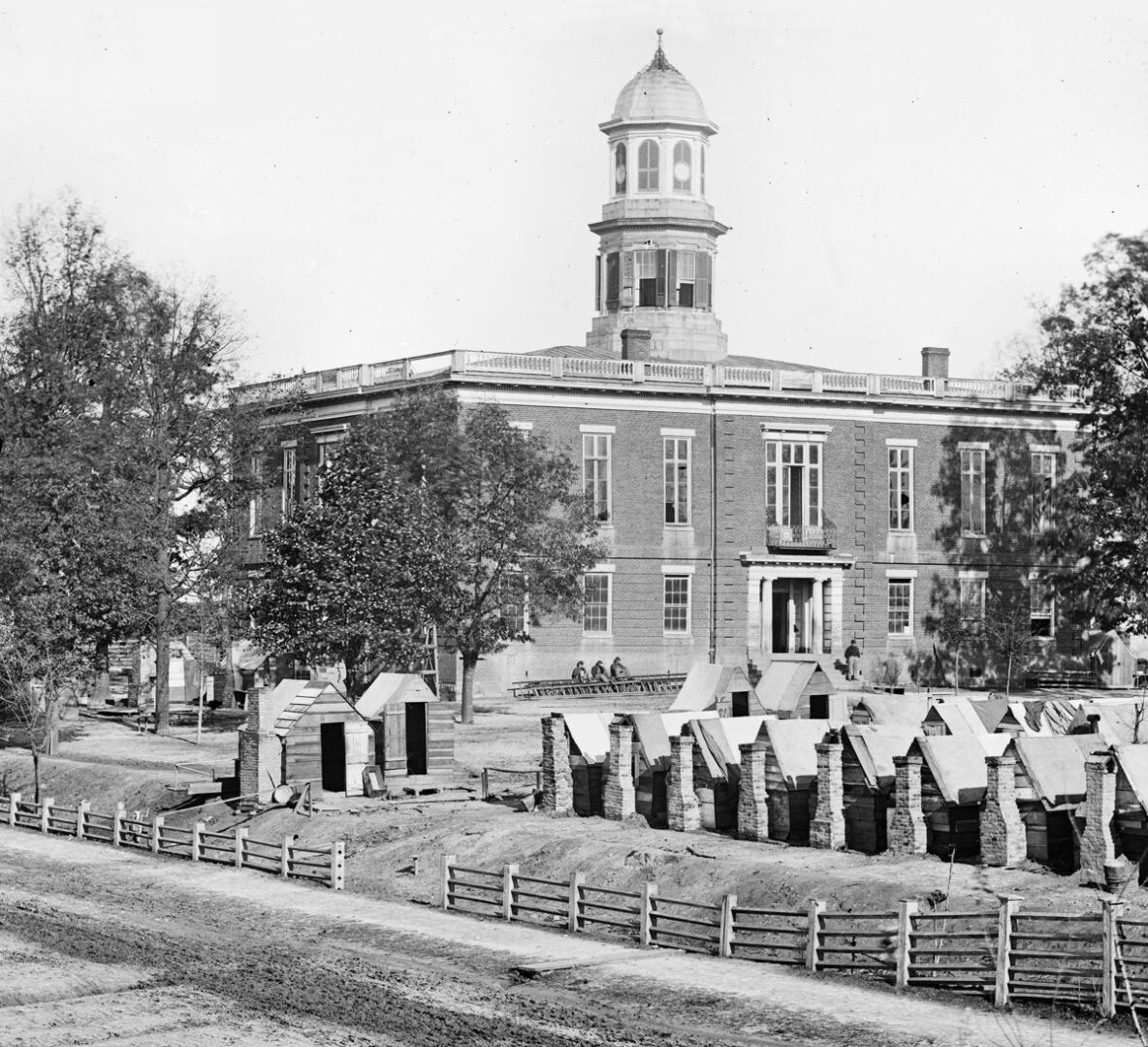

In 1867 the U.S. Congress assumed control of Reconstruction efforts (1867-76) in the South, with Georgia and other southern states again placed under military authority. Major General John Pope was placed in command of Georgia on April 1, 1867, and shortly afterward took up his duties in Atlanta. A new constitutional convention was called for the state, and General Pope ordered the convention to assemble in Atlanta, reportedly because Milledgeville innkeepers had proclaimed that Black delegates would not be welcome in their inns. The convention met in Atlanta from December 1867 to March 1868.

During this session, Atlanta city officials again made a bid for the city’s designation as the state capital—especially in light of Atlanta’s recent population growth and better rail accessibility. In February 1868, the Atlanta City Council held a special meeting to frame a formal proposal to the constitutional convention. Essentially, the council’s offer was that Atlanta, if designated as Georgia’s capital, would provide suitable buildings for the legislature, the governor, other state officials, and the supreme court at no charge for ten years. Additionally, city officials offered the twenty-five-acre fairground or the choice of any unoccupied ten acres in the city for a state capitol.

The constitutional convention accepted the offer and included in the Constitution of 1868 a formal provision: “The seat of government of this State, from and after the date of the ratification of this constitution, shall be in the city of Atlanta, and the general assembly shall provide for the erection of a new capitol, and such other buildings as the public welfare may require.” By a vote of 89,007 to 71,309 the new constitution was ratified in April 1868. Georgia now had a new capital—its fifth in less than a century.

Subsequently, the Milledgeville capitol building served as Baldwin County’s courthouse for several years. In 1879 it was converted into the Middle Georgia Military and Agricultural College (later Georgia Military College). Though severely damaged by fire in 1941, the building was rebuilt and continues to be used by the school today. In 2000 the Old Capitol was restored. And in 2001, it once again served as the state capitol—although only for a day. To recognize the 250th anniversary of representative government in Georgia, Governor Roy Barnes addressed a joint session of the General Assembly in the Old Capitol.

Atlanta: Georgia’s Fifth Capital

On June 30, 1868, a train of sixteen railcars left Atlanta for Milledgeville with an order from the provisional governor to bring back the statehouse furniture and furnishings. Included in this inventory were five full-length paintings—of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, the Marquis de Lafayette, James Oglethorpe, and George Washington—painted by C. R. Parker in 1826. The portraits of Oglethorpe and Lafayette had hung in the house chamber, while those of Washington and Jefferson had adorned the senate chamber. Today, these paintings hang in the capitol rotunda and represent some of the few surviving artifacts from the Milledgeville capitol.

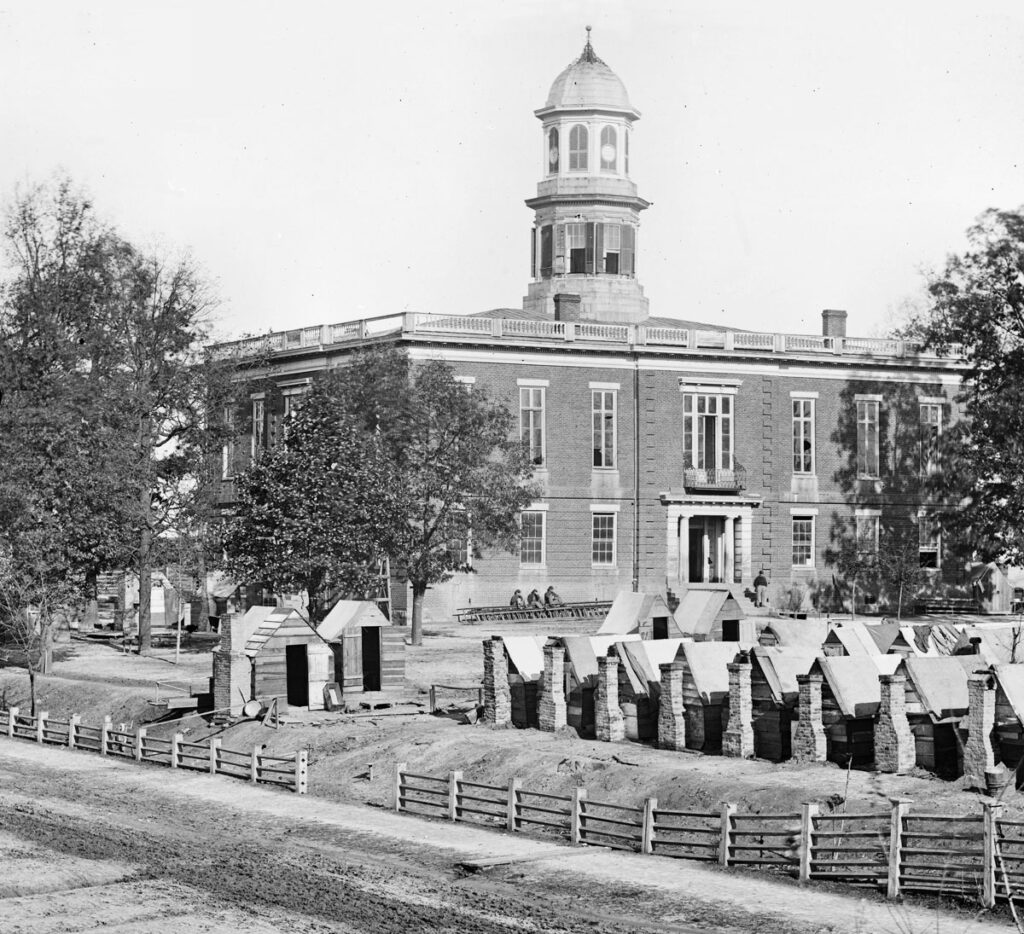

On July 4 the first meeting of the legislature in Atlanta took place in the Atlanta City Hall and Fulton County Courthouse. This structure, built on the same site as today’s capitol, served as the statehouse from July 1868 to January 1869, although it was immediately apparent that the building was not large enough. In August 1868 Atlanta’s city council met with a house committee on the matter, and the city offered either to construct an addition to city hall or to complete an unfinished opera house in Atlanta to be used by the legislators. The legislature chose the latter.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In 1867 the Atlanta Opera House and Building Association had acquired the southwest corner of Marietta Street and Forsyth Street and begun construction of a five-story opera house. By 1868 the outside walls had been erected, but the association’s funds were depleted, and construction was halted. At a receiver’s sale on June 2, 1868, the unfinished structure and the land on which it stood were purchased by Edwin N. Kimball for $31,750.

Within two months Kimball and his brother, H. I. Kimball, were promoting the idea of completing the building and outfitting it for use by the legislature, with the Kimballs promising to have it ready by January 1, 1869. Their proposal also stipulated that Atlanta would rent a portion of the building for five years at $6,000 per year and turn over the rented portion to the state. At the end of the five years, the legislature would either purchase the building or authorize the erection of a new statehouse at another location.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

By January 1869 the new building—which would serve as the state capitol for the next two decades—was ready for occupation by the state legislature. In August 1870 the General Assembly approved the state’s purchase of the Kimball Opera House.

Georgia’s Current Capital

In the 1870s, after Reconstruction had ended, the location of Georgia’s capital city again became a matter of debate. A constitutional convention met in Atlanta in 1877, and the question of Georgia’s capital was put before the body.

The convention decided that the location of the capital should be kept out of the new constitution, but it passed an ordinance declaring that, at the next general election, voters of the state would decide between Atlanta and Milledgeville. Soon a spirited competition developed between the two cities over which should be the site of the state capital. More than a million circulars concerning the Milledgeville-Atlanta battle were sent out in 1877, with nearly every Georgia newspaper taking a position on the issue.

Speeches were made across the state, with Milledgeville supporters associating Atlanta with the abuses of Reconstruction and arguing that the temptations of the big city were too great for members of the legislature. Additionally, Milledgeville supporters pointed to the Old Capitol Building awaiting the return of the state government, whereas new facilities would have to be constructed if the capital remained in Atlanta. On the other side, Atlanta supporters pointed to the growing importance of Atlanta within the state, emphasizing the city’s superior rail facilities.

On December 5, 1877, voters across Georgia reaffirmed Atlanta as the capital city of Georgia by a vote of 99,147 to 55,201. Two years later, in 1879, the legislature accepted Atlanta’s proposal and selected the city hall as the site for the new capitol.

Today, it seems unimaginable that Georgia would move its capital city again. Except for an unsuccessful effort by Macon boosters in 1919 to have that city designated the state capital, there have been no serious efforts to move the capital. Interestingly, however, there have been efforts to decentralize state government by moving some agencies or divisions to other locations in Georgia. For example, the secretary of state has moved some of the functions of that office to Tifton and Macon. In 2003 the state archives moved to a new facility in Morrow. The Department of Natural Resources also has moved some of its offices to other cities. While decentralization may continue, most state government officials and agencies likely will remain in the state capitol complex in Atlanta.