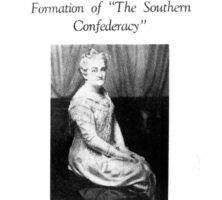

The Lucy Cobb Institute, a secondary school for young women in Athens, was founded in 1859 by Thomas R.R. Cobb, a prominent lawyer and proslavery writer.

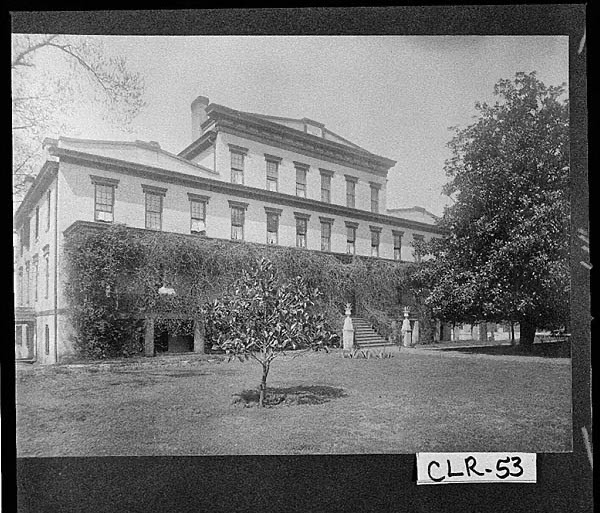

Between 1880 and 1928 Cobb’s niece Mildred Lewis Rutherford, a Lucy Cobb graduate, taught at the school. She served as principal for twenty-two of those years. Rutherford’s work in women’s clubs, most significantly the United Daughters of the Confederacy, made her one of the best-known women in Georgia of her day. Her national reputation as a historian of the Civil War (1861-65) and the Old South brought the school widespread recognition and respect.

Cobb had hoped that his young daughter Lucy would attend the new school, but she died before it opened, and the institute’s board of directors named the institute in her honor. Most Lucy Cobb students came from wealthy and well-established families. Nineteenth-century schools for elite young women emphasized subjects that would enhance their gentility, including art, music, and French, and Lucy Cobb was no exception. Yet even from its early days, the school offered a more academically serious curriculum than the stereotypical finishing school.

Under the leadership of Rutherford and her sister Mary Ann Lipscomb, the curriculum became even more rigorous. Students, or “Lucies,” in the collegiate track studied sciences (including chemistry and physics), higher mathematics (algebra, geometry, trigonometry), logic, rhetoric, languages, history, and literature. After 1918, once the University of Georgia (UGA) began accepting women students, graduates of Lucy Cobb’s collegiate program could enroll. Indeed, the school aimed its curriculum to prepare graduates to attend the university. In her extensive 1916 report on women’s education in the South, Elizabeth Avery Colton of the Southern Association of College Women listed Lucy Cobb as one of the very best schools for young women in Georgia.

Along with academics, Rutherford and other faculty members emphasized the importance of a modest appearance and proper manners and etiquette. Students were prohibited from venturing beyond the school’s front yard unchaperoned, entertaining male visitors, attending parties in town, dancing, and wearing makeup or short skirts. The combination of academic rigor with education in gentility, their teachers believed, prepared students for both private and public life. Alumnae became clubwomen, librarians, teachers, authors, and businesswomen; one Lucy Cobb graduate, Caroline Goodwin O’Day, served in the U.S. Congress (1935-43).

Despite its success, the institute struggled to maintain high enrollment and keep its bills paid. The school faced acute financial difficulties in the 1920s, mostly because of the agricultural depression that hurt the entire state. After Rutherford’s death in 1928, the school struggled on for a few more years, finally closing in 1931. UGA purchased the building, but it fell into disuse.

In the 1970s a group of Athens preservationists, many of them children or grandchildren of alumnae, received a federal grant to renovate the exterior of the institute’s Seney-Stovall Chapel. This renovation effort was led by historian Phinizy Spalding, the grandson of alumna Nellie Stovall, who was instrumental in the original construction of the chapel. In the early 1880s, while a student at the institute, Stovall appealed to New York philanthropist George I. Seney for building funds, and the chapel, which bears both of their names, was completed in 1885.

The entire Lucy Cobb complex was renovated in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with two appropriations by the U.S. Congress of $3.5 million and $1 million, and contributions of another $1 million by public and private donors. The Lucy Cobb Institute’s inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places was a major consideration in the appropriation of federal funds. In 1991 the institute became the central administrative home of the Carl Vinson Institute of Government at UGA.