Located in the mountains of northeast Georgia, Tallulah Falls rose to prominence as a resort area in the late nineteenth century. Early in the twentieth century, after a fierce struggle with conservationists led by Helen Dortch Longstreet, the Georgia Power Company dammed the waterfalls and constructed a large hydroelectric facility at the site. Georgia Power and the state of Georgia teamed to establish the Tallulah Gorge State Park, and thousands of Georgians visit the area annually.

Tallulah Falls was actually a series of four main cataracts and several smaller rapids that dropped approximately 350 feet over the course of a mile. After gathering speed through the Indian Arrow Rapids at the head of the falls, the Tallulah River raced down L’Eau d’Or, a forty-six-foot-tall cataract. Tempesta, estimated at eighty-one feet, was the second fall, followed by the largest cataract, Hurricane, which dropped ninety-six feet. Oceana, approximately a forty-two-foot drop, was the final major falls. The gorge through which the river cut created steep cliffs and rock outcroppings that provided excellent observation points and added to the scenic beauty of the falls.

Photograph by Jeno

The Rise of Tourism

The Cherokee Indians inhabited the land surrounding the gorge before the arrival of European settlers around 1820. The Cherokee called the falls Ugunyi, but the settlers named the gorge and falls Tallulah. While the Cherokee viewed the falls with trepidation and largely avoided the area, white settlers and travelers commented on the awe-inspiring beauty of the falls and gorge in newspapers and travel books. Some visitors compared Tallulah Falls to other legendary cataracts, and Tallulah was soon dubbed the “Niagara of the South.”

As word of Tallulah Falls’ beauty spread in the mid-nineteenth century, more visitors started making the trek to the north Georgia mountains. By the early nineteenth century, local as well as national writers extolled this scenic wonder to broad readerships, which increased its allure to tourists, who had to travel for days over mountain trails to see it. The artist George Cooke painted Tallulah Falls in 1841, which depicts three of the four cataracts: L’Eau d’Or, Tempesta, and Hurricane. Artist and writer Thomas Addison Richards made his engravings of the falls and the gorge a focal point of his book Georgia Illustrated, published in 1842, and made them the title piece of a collection of stories and sketches a decade later, Tallulah and Jocassee (1852). Other antebellum writers extolled the breathtaking beauty and power of this “very grand and wild scene, an immense chasm or ravine,” and many commented on the tremendous sound the rushing water produced.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

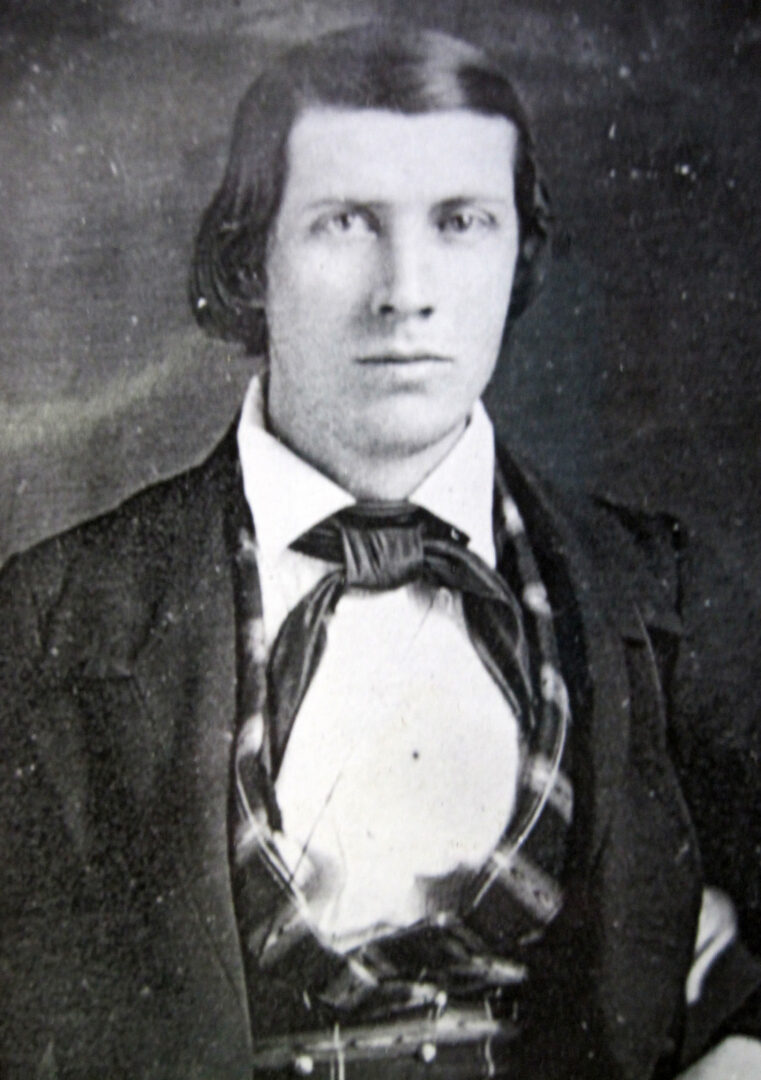

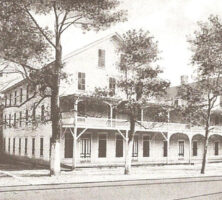

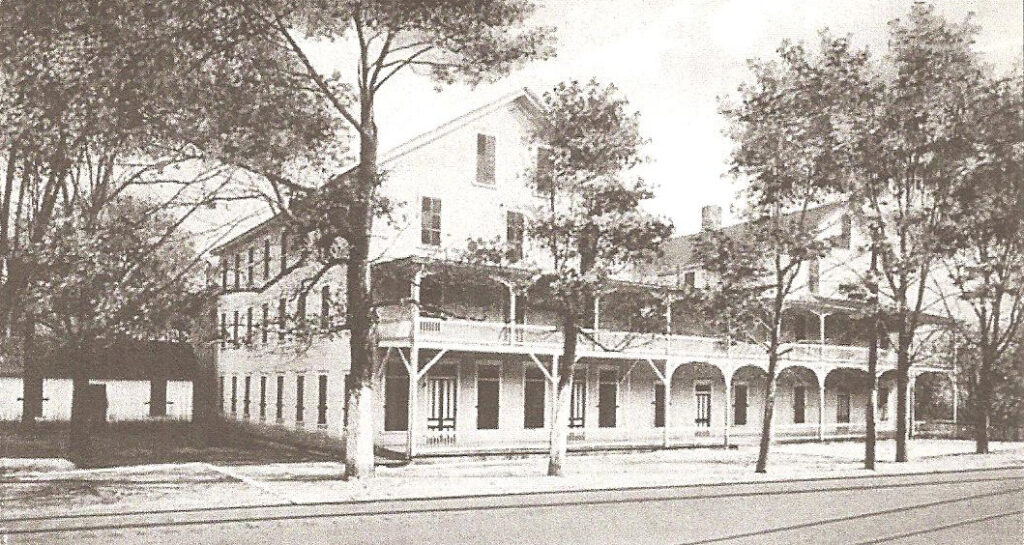

In 1882 the extension of the railroad decreased the travel time between Atlanta and Tallulah Falls from days to hours and made the trip affordable for more Georgians. Nearly twenty hotels and boardinghouses sprang up around the falls to accommodate the increased number of visitors. The first of these establishments, the Cliff House Hotel, opened in 1882 and operated until 1937, when it burned in a kitchen fire. The hotel was owned by Rufus L. Moss Sr., a prominent Athens businessman, director and trustee of the Northeastern Railroad, and cofounder of the town Tallulah Falls. Moss also owned a significant amount of land around Tallulah Gorge and built a family home, Pine Terrace, there in 1879.

Courtesy of Rabun County Historical Society

In addition to its many lodgings, the town of Tallulah Falls had three churches, a railroad depot, a telegraph office, a post office, a bar, and for a brief time in 1897, a newspaper, all largely supported by the tourist industry. Besides enjoying the beauty of the falls, visitors could go horseback riding, hunt, fish, bowl, or play tennis during the day; nightly entertainment included music, dancing, and card playing.

Damming the Falls

While the tourist industry flourished, the hydroelectric industry was just beginning to expand in Georgia. Soon after the turn of the century, several corporations vied for the right to develop Tallulah Falls. In 1909 the Georgia Power Company purchased a significant tract of land from Moss for $108,960 and began work on a dam. After experiencing financial difficulties with the project, Georgia Power merged with both the Morgan Falls hydroelectric plant on the Chattahoochee River and the Georgia Railway and Electric Company, forming the Georgia Railway and Power Company (GR&PC) in 1912.

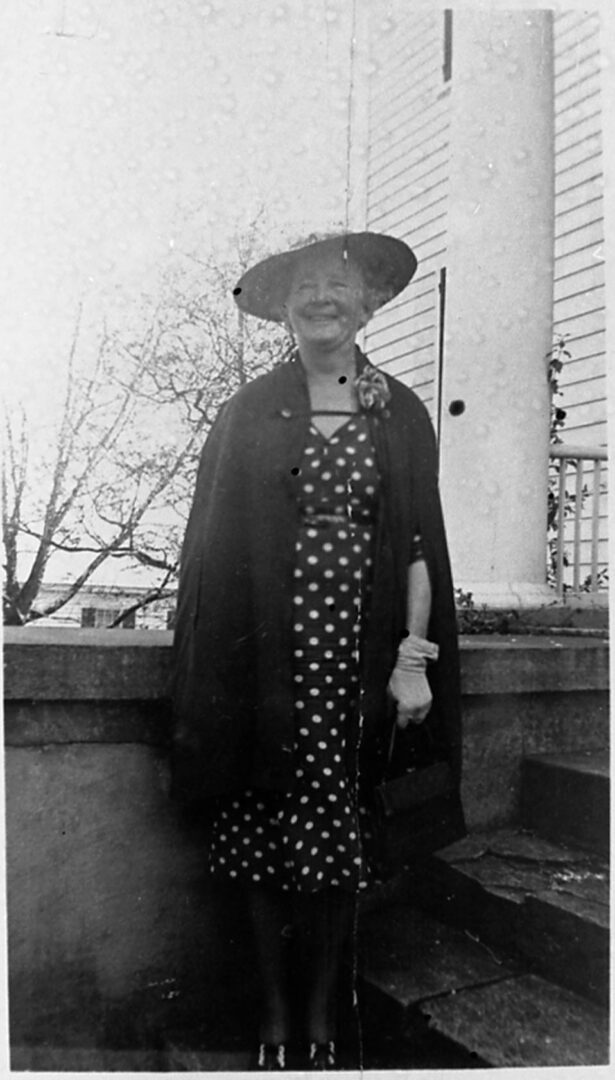

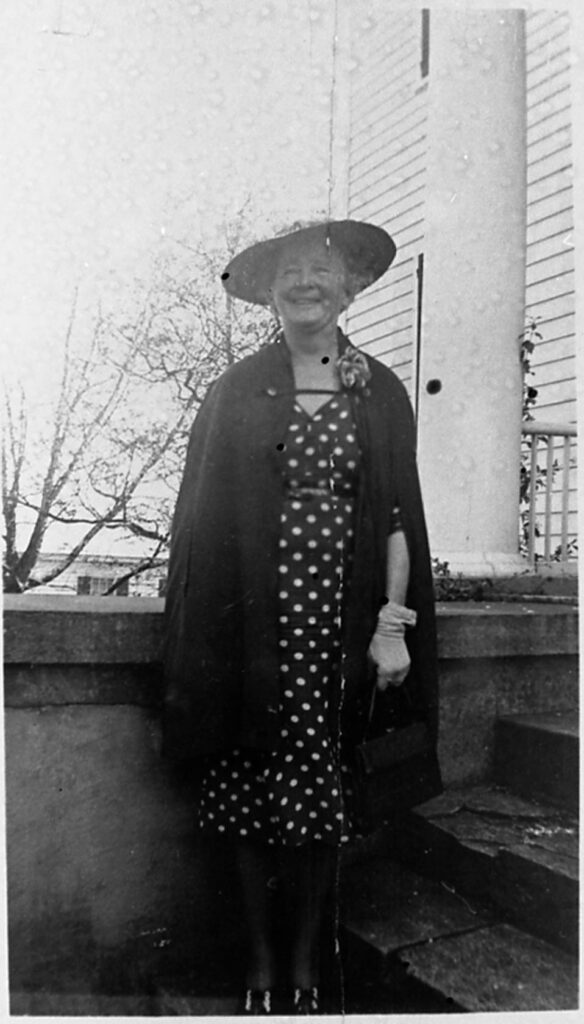

As development of the dam continued, Helen Dortch Longstreet, the widow of Confederate general James Longstreet and a resident of nearby Gainesville, feared that its construction would destroy the falls and detract from the area’s beauty. In 1911 she organized the Tallulah Falls Conservation Association to stop the dam’s construction and turn the area into a state park. Her efforts launched one of the first conservation movements in Georgia. Longstreet’s successful lobbying of the state legislature in 1912 forced the attorney general to bring suit against GR&PC, but the power company prevailed the following year in a Rabun County jury trial and in a subsequent appeal to the state supreme court.

Completed in 1913, the dam was a masonry structure 116 feet tall and 400 feet long, and it created a lake with a surface area of 63 acres. An underground tunnel 6,666 feet long, blasted through solid rock, took water from the lake to a holding area above the powerhouse, where it fell 608 feet and was converted into electricity. The Tallulah project became the centerpiece of a multidam project on the Tallulah and Tugaloo rivers, which provided electricity for Atlanta and the rest of north Georgia. The dam, once the largest single producer of electricity in the state, is still in operation but is now a minor component in a huge system.

Photograph by Jeno

In 1992, nearly eighty years after the completion of the dam, the state, in partnership with Georgia Power, created Tallulah Gorge State Park, one of the most popular in the state park system. Visitors enjoy activities on the lake and hiking through the gorge, and controlled releases from the dam allow them to hear the roar of the falls on selected weekends in the spring and autumn. In 1999 the trail around the gorge was named for Helen Dortch Longstreet.