The Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA) held their first official meeting in 1972 and built an activist lesbian community through its end in 1994. Outlasting many of its better-known sister organizations outside of the South, ALFA’s legacy is the remarkable Southern Feminist Library and Archives, which offers a rich collection of global lesbian history.

Formed in response to women’s frustration with the gay liberation and women’s liberation movements of the 1960s, ALFA provided a space for lesbians and feminists who hoped to escape both the discrimination that pervaded these liberation groups and the sexism of the New Left generally. Women who learned activism from their work in the Black civil rights movement and anti-war actions joined together in Atlanta’s Little Five Points neighborhood. There they worked to address racism in all forms, while also focusing on sexism, abortion rights, body oppression, environmental issues, women’s liberation, anti-war activism, anti-Semitic action, eliminating economic oppression, and promoting accessibility. Because queer activist organizations were often rife with sexism, with the Gay Liberation Front in Atlanta largely controlled by gay men, ALFA focused on the need for queer women’s spaces and activism devoted to women’s needs. At ALFA, women came first.

ALFA held its first meeting on June 23, 1972. Membership drew from predominately white college students at nearby Georgia State University and Emory University. Decimated by white flight in the 1960s, Little Five Points attracted freethinkers, political activists, artists, lesbians, and feminists who were free to pursue their vision in a neighborhood that offered rough, yet affordable, housing. The original ALFA house was located at 1190 Mansfield Avenue Northeast. The group later moved to another house on McLendon Avenue. Women who were engaged in political organizing and communal living defined the development of the neighborhood. They built coalitions with a variety of queer and anti-racist groups, including anti-Klan organizations. Notable women visited ALFA house, including authors Rita Mae Brown and Ann Allen Shockley, and Del Martin, co-founder of the first national lesbian homophile organization, Daughters of Bilitis.

In the beginning there were no dues, but an ALFA membership would eventually cost six dollars. In exchange the organization offered dances and picnics, films, and talent shows. ALFA women hosted rap groups to chat about issues of concern, held feminist consciousness awareness meetings, and offered counseling to women considering their sexuality. From its formation, the group quieted the divisive debates of lesbian separatism by welcoming all women, though lesbians remained at the center of the group. In ALFA, women found an opportunity to focus solely on their lesbian-feminist goals. Even before the group formed, ALFA’s future members were present at Atlanta’s radical queer Pride gatherings. Founding members participated in the first southern U.S. Pride gathering, which occurred in Piedmont Park in 1970, and some future ALFA women marched with a queer contingent a year later in the streets of Atlanta. At the local, regional, and national level, ALFA women organized and attended events in support of the Equal Rights Amendment. ALFA’s leaders organized and traveled to Washington D.C. to represent Georgia in the national gay rights marches held in 1979 and 1987, proudly displaying their Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance banner.

ALFA activists worked at both local and national levels on matters of importance to women and queer people. Members served as diplomats to the Atlanta Police Department to inform on issues of police harassment that affected the city’s queer citizens. And in national matters of violence against women, like the case of Joan Little, who killed her prison guard rapist in North Carolina, ALFA joined with women throughout the Southeast to rally and raise awareness. Through their local and national media committees, women worked to increase representation of lesbians by communicating with television and radio outlets to identify sexism and homophobia in their programming. When ALFA identified offensive material in the media, their committees would request the removal of the content or call attention to the exclusion of woman-centered news. ALFA members wrote letters, but they also picketed media organizations like the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution newspapers (now the Atlanta Journal-Constitution). In local publications like the queer Pulse and the liberal Great Speckled Bird, ALFA women found a platform to publicize their activism in the community.

ALFA’s political commitments often overlapped with their social offerings. In 1975 the organization hosted Atlanta’s Great Southeast Lesbian Conference with the theme of “Building a Lesbian Community.” The event drew women from across the nation while demonstrating ALFA’s role as the lesbian headquarters of the South. Perhaps the most important social benefit of the organization was its softball teams, notably the ALFA Omegas. Women’s softball teams competed nationally, allowing lesbians from Atlanta to build community around the country. When very few spaces were completely devoted to women, the softball field offered community and sisterhood.

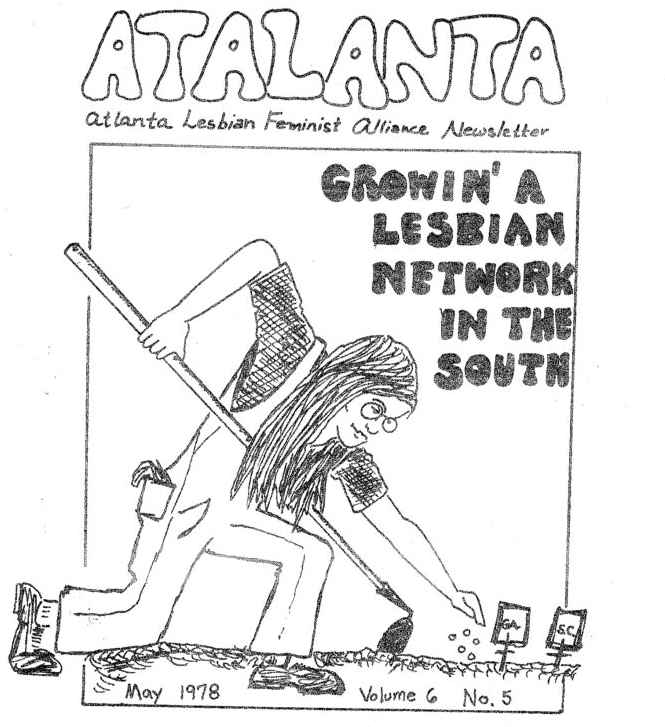

ALFA’s impressive, self-built library, the Southern Feminist Library and Archives, provided a resource for lesbians and feminists seeking information and looking to make regional and national connections. From its founding, the organization actively gathered and sought donations of writings authored by and about women. Through their efforts, the group preserved a rich collection of international feminist history, or “herstory.” The women of ALFA self-published their own monthly newsletter, Atalanta, named after a huntress from Greek mythology and meaning “equal in weight.” Women around the world mailed their newsletters to ALFA, and members filed them in their library. In turn ALFA mailed their newsletter to other women’s groups so that news of Georgia’s queer life circulated across the nation and other parts of the lesbian world, connecting feminist lesbians in Atlanta to their global sisters.

The women of ALFA built a southern lesbian stronghold in the heart of Georgia. By reaching out and working within the structures of policing, the group pioneered the fight for safe queer spaces. Through their media committees, they increased the possibilities for women’s visibility in the public arena. In addition to refuge in the 1970s and 1980s, ALFA provided and continues to provide access to lesbian feminist education. Though the group dissolved in 1994, ALFA’s legacy persists due to its commitment to women’s writing, publishing, and the Southern Feminist Library and Archives. The majority of ALFA’s collection now resides at Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library.