The twentieth-century effort to mobilize Black Georgians in the political process began during the 1930s and continues to the present. It involves a broad base of individuals and organizations whose common goal is to enhance Black political influence and representation in all three branches of government. During the first years of the twenty-first century, a renewed effort has been made to organize and mobilize the African American community.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Historical Overview

During the 1930s Atlanta University Center professors began to organize “citizenship schools” designed to prepare African Americans to participate in the political process. Because Georgia had a whites-only primary at the time, Blacks did not have any influence in determining the Democratic nominees, who usually ran unopposed or with only token opposition in the general election. Therefore African Americans had little interest in registering to vote or in voting on election day. Such white politicians as Governor Eugene Talmadge ignored the Black electorate and pledged to maintain segregation in Georgia forever. Even the liberal Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield told Black political leaders that more African Americans would have to register as voters before he would consider their requests to hire Black policemen, install street lights, pave roads, or improve city services in their communities.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

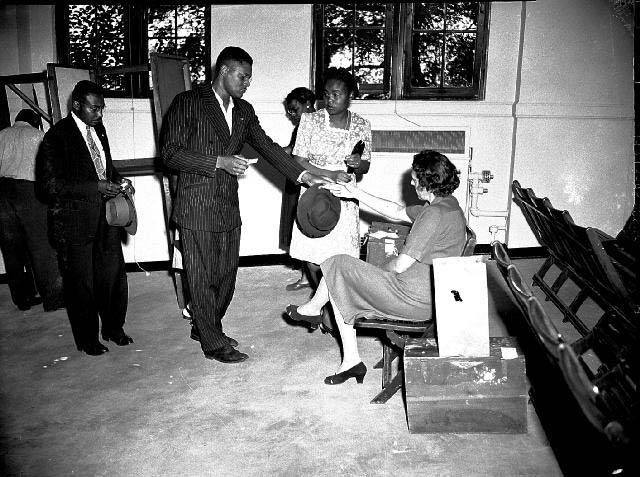

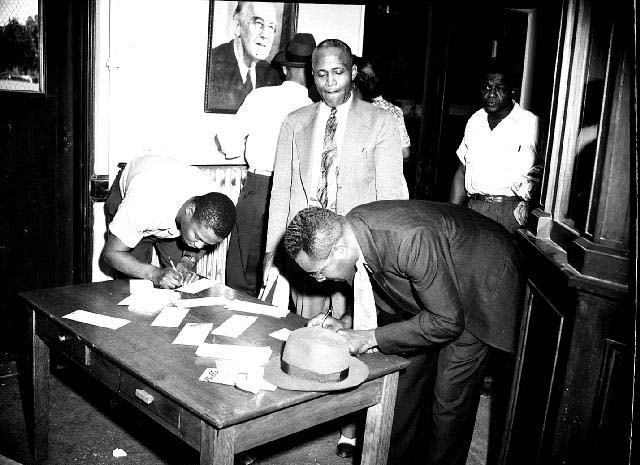

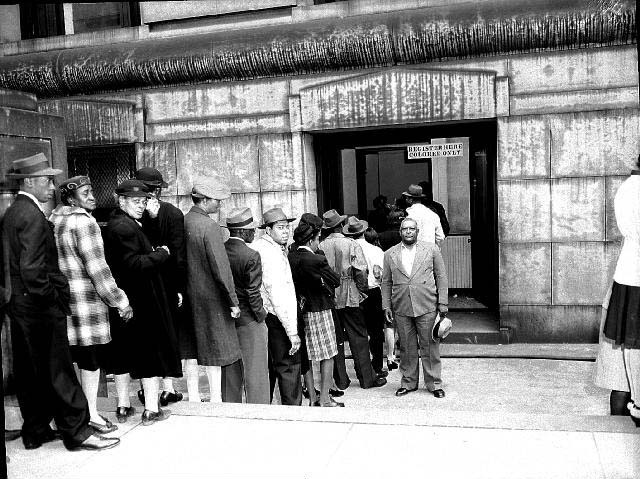

Several Black plaintiffs filed suits in federal court against the whites-only primary, and in the 1946 King v. Chapman et al. decision, the Fifth District Courtof Appeals upheld a 1945 ruling that declared the white primary in Georgia unconstitutional, saying that the primary was an integral part of the election process and thus could not exclude Black voters. Historically, the Atlanta Negro Voters League, comprising religious, business, civic, political, and university leaders, would interview white candidates, recommend the best candidates for the Black community, and disseminate their choices at churches and on the Black-owned radio station, WERD. More than 90 percent of Blacks usually voted for the recommended slate.

In 1946 the Atlanta Urban League spearheaded a coalition of groups—including Black Republicans, Black Democrats, and members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—that registered 14,368 new Black voters in a two-month period. Mayor Hartsfield was then willing to make some concessions to the Black community. During the civil rights movement, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964), required elections to be based on the one-man, one-vote principle, and more Blacks registered after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Subsequently, Black voters elected seven state representatives and two senators to the Georgia legislature.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The next major mobilization effort occurred in 1973, when the University Movement for Black Unity, organized primarily by professors and students in the Atlanta University Center, worked to elect Atlanta vice mayor Maynard Jackson the first Black mayor of Atlanta. The African American voter turnout was more than 10 percent higher than the white turnout in this historic election.

The 1991 redistricting/reapportionment legislative session provided an opportunity to elect three Black legislators to the U.S. Congress in 1992: Sanford Bishop, John Lewis (who had been a member of the House since 1987), and Cynthia McKinney. In 1998 two Black candidates, Michael Thurmond and Thurbert Baker, ran and were elected to the statewide offices of commissioner of labor and attorney general, respectively. A massive Black voter turnout in Fulton and DeKalb counties, partly resulting from some racist campaign tactics by Mitch Skandalakis, the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor, also helped to elect Democrats as both governor (Roy Barnes) and lieutenant governor (Mark Taylor).

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Recent Organizational Activities

Since 1997 the Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda (GCPA), headed by Joseph Lowery, former president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), has developed the most comprehensive political mobilization program in the past fifty years. A detailed agenda was developed on a dozen public policy issues. Four major components in its strategy were

•creating a statewide 2002 “Voter Empowerment Crusade” and holding meetings at churches and community sites to discuss candidates, political issues, and voting;

•compiling demographic data in the counties, including information about African American population percentage, Black voting-age population, Black active voters, number and percentage not registered, and monthly voter-registration goals;

•distributing to voters survey results on candidates for statewide congressional offices; and

•mounting continuous voter-registration and get-out-the-vote efforts for all elections.

Periodic “Voter Empowerment Sundays” are held to encourage churches to organize voter registration drives, distribute election information important for Black Georgians, host political forums to discuss issues, and coordinate demonstrations of the new computerized touch-screen voting machines.

The GCPA includes the Baptist Ministers Union, Concerned Black Clergy, Georgia AFL-CIO, Georgia Association of Black Elected Officials, Georgia Coalition of Black Women, Georgia NAACP, Georgia Summit of African American Business Organizations, Juvenile Justice Task Force, National Council of Negro Women, National Youth Connection, 100 Black Men of Atlanta, Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, Progressive Baptist Convention, SCLC, and SCLC W.O.M.E.N.

The GCPA pledges to maintain its activities on a year-round basis so that it can maximize African American political involvement in elections at all levels of government. The goal is to monitor elected officials, secure their support of the GCPA’s agenda, inform their constituencies of elected officials’ votes on key issues, increase Black voter registration, and maximize voter turnout at every election. This comprehensive effort at perpetual mobilization is unique in Georgia. However, it will take two or three election cycles before an evaluation of its relative success is possible.