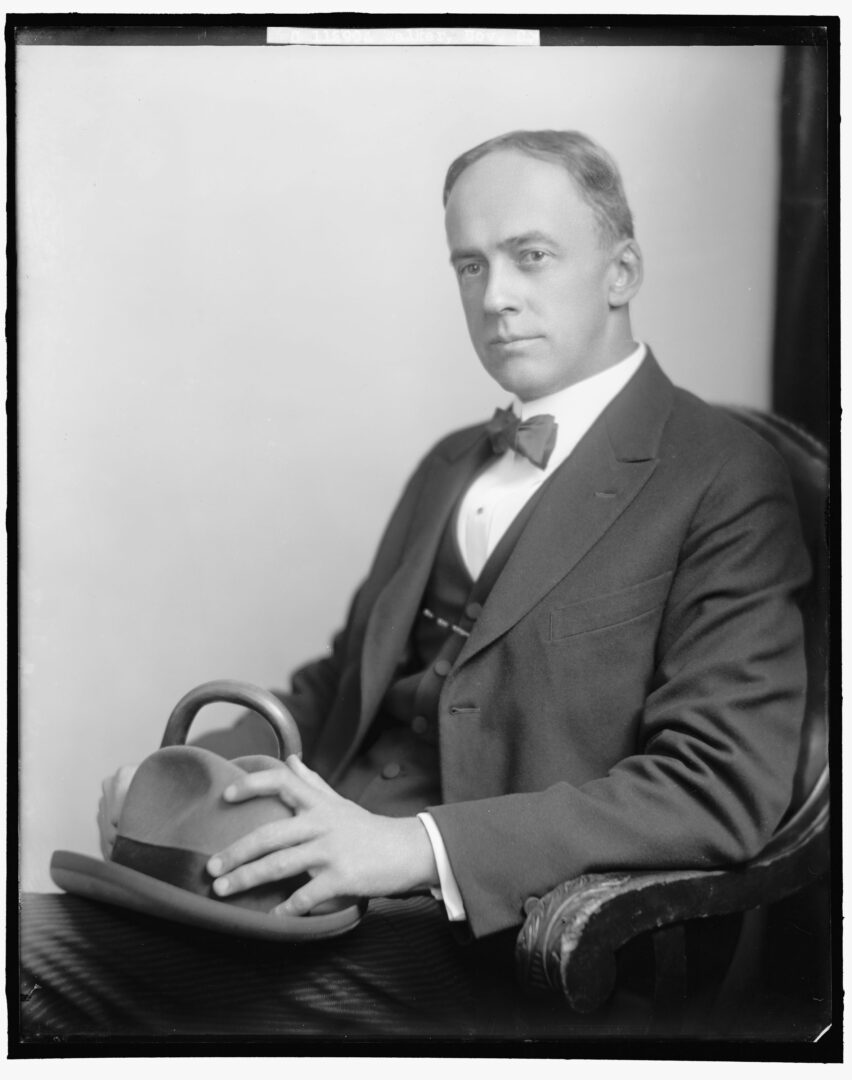

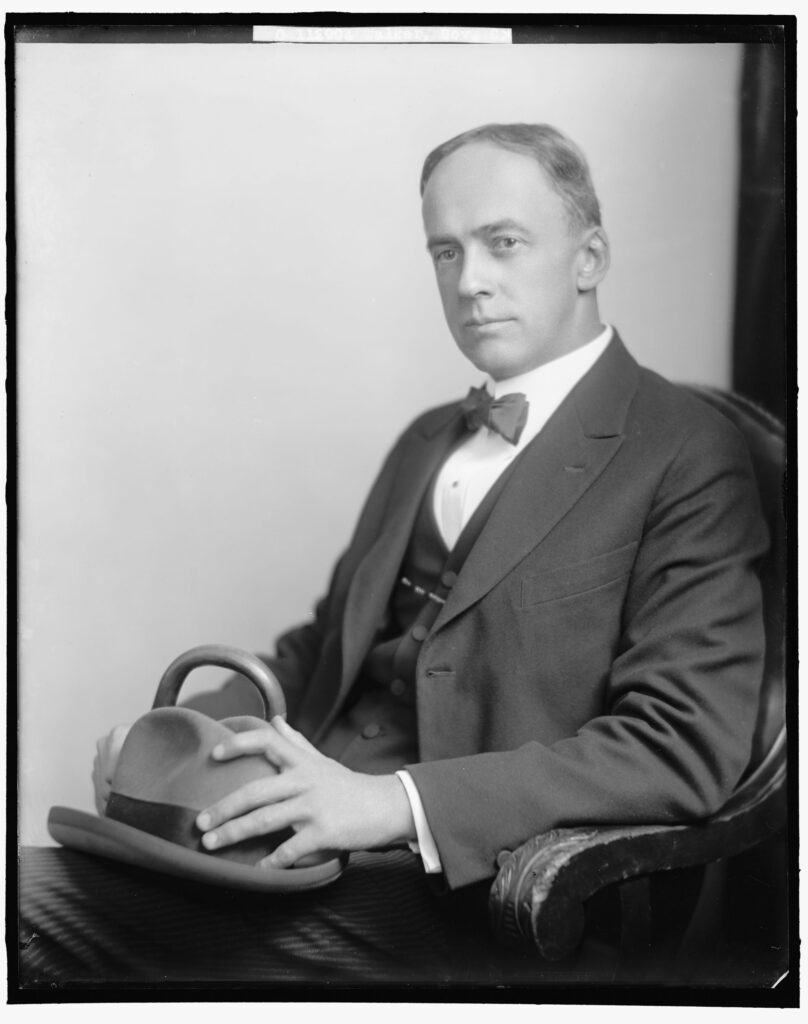

Clifford Walker served as Georgia’s sixty-first governor, from 1923 to 1927. Holding office during a period of transition in Georgia politics, Walker accomplished little of note legislatively during his administration and is best remembered for his ties to the Ku Klux Klan.

Early Life and Career

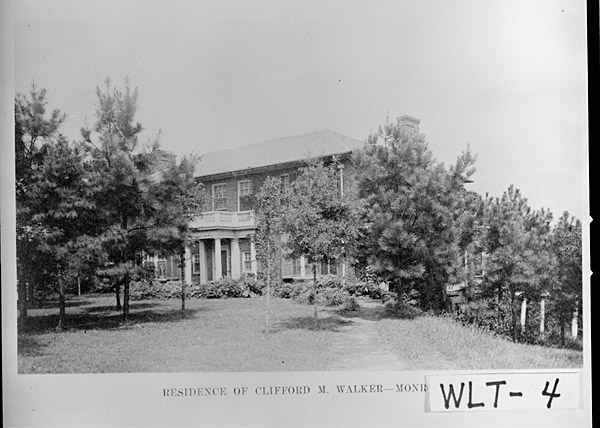

Clifford Mitchell Walker was born on July 4, 1877, in Monroe to Alice Mitchell and Billington Sanders Walker. One of seven children, he was educated at the Georgia Military Institute and the University of Georgia (UGA). Walker proved to be a gifted student, and while at UGA he established the Georgian, a literary magazine, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. After receiving a degree from UGA in 1897, he returned to Monroe, where he worked for the attorney R. L. Cox. Walker was admitted to the state bar association in 1898. He married Rosa Mathewson in 1902, and they had three sons.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Walker was elected mayor of Monroe in 1902. He served in that post until 1904, and after leaving politics for five years, he again became a public official in 1909, when he began serving as the Western Circuit solicitor general, a post he held until 1913. After a two-year break from public office, Walker was elected attorney general for Georgia in 1915. In 1920 he resigned as attorney general to run for governor.

Klan Influence

By 1920 the Ku Klux Klan had become a powerful force in Georgia politics. The original Klan, organized during Reconstruction, had faded away by the beginning of the 1870s. Revived during a ceremony on Thanksgiving Day in 1915 atop Stone Mountain, the second Klan quickly gained popularity in Georgia and across the nation. During the 1920 gubernatorial primary, Walker’s opponent, Thomas Hardwick, recognized the importance of the Klan and praised the organization. As a result, Walker was soundly defeated.

While governor, however, Hardwick turned against the Klan and fell out of favor with the organization. Walker again ran for governor in 1922 and, after soliciting Klan support during the race, easily defeated Hardwick. Unlike his predecessor, Walker remained loyal to the Klan while governor. He addressed a national Ku Klux Klan convention, where he promised to meet with Klan leaders in the state on policy issues. Walker kept his word and often consulted Klan leaders on matters regarding state policy. In 1924 Georgia voters elected Walker to a second term.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Despite his close ties to the organization, Walker did not openly discuss his support for or membership in the Klan. In September 1924 the journalist Julian Harris, son of Georgia author Joel Chandler Harris, revealed that Walker belonged to the Klan and had traveled secretly to Kansas City, Missouri, for a meeting with organization officials. Walker at first denied the charges, but consistent pressure from Harris and others eventually led the governor to admit that he had joined the Klan and made the trip to the Midwest. The remainder of his second term passed uneventfully, and in 1926 Walker was replaced in the governor’s chair by Lamartine Hardman.

Legacy

Wedged between the era of Thomas E. Watson and that of Eugene Talmadge and Herman Talmadge, little of note happened in Georgia politics during the 1920s. Historian Numan Bartley comments wryly that during the period, “Georgia government was more notable for its antics than for its accomplishments.” Although Walker campaigned on a platform calling for the complete overhaul of the tax system, a reduction in the number of government offices, and the provision of free textbooks to public schools, the General Assembly rejected most of his programs. Walker did manage, however, to create the state forestry commission and the auditing and revenue departments.

In 1928 Walker moved from Monroe to Atlanta and entered into private law practice. Five years later he and Joseph B. Kilbride founded the Woodrow Wilson College of Law, also in Atlanta. He served as general counsel for the Georgia Department of Labor for fifteen years, from 1937 to 1952. He died on November 9, 1954.