In the summer of 1941 Governor Eugene Talmadge instituted the most devastating assault on higher education in the history of Georgia. His firing of professors, administrators, and members of the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia generated a storm of adverse publicity throughout the nation and led the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to withdraw accreditation from all of Georgia’s state-supported colleges for whites. Walter Cocking, dean of the College of Education at the University of Georgia, was a key target in the Talmadge purge.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

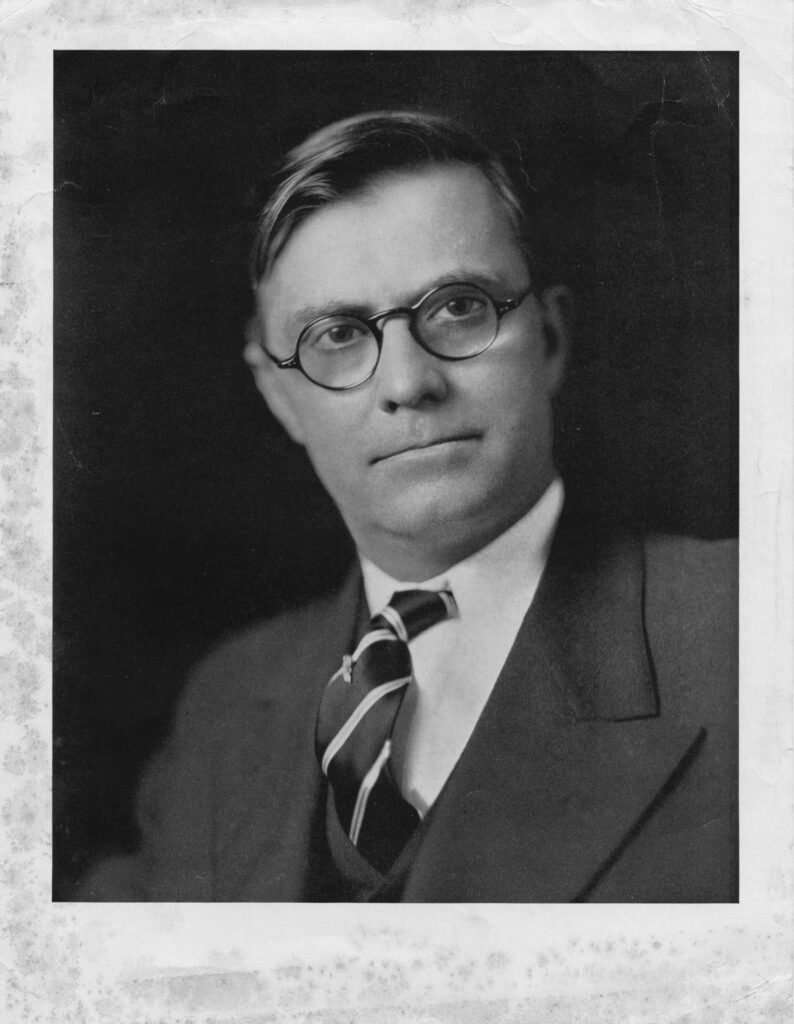

A native of Iowa, Cocking earned his doctorate at Columbia University in New York and compiled an outstanding record of scholarly achievement before his arrival in Georgia in 1937. After holding important administrative positions in Iowa, Texas, and Missouri, he served for five years as professor of school administration at the George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee, and was commissioner of education for Tennessee from 1933 to 1937. Hired to improve the academic standards at the University of Georgia’s maligned College of Education, he quickly instituted reforms that accomplished that goal, but his brash and domineering style offended members of his staff.

At the May 30, 1941, meeting of the Board of Regents, Talmadge, who was an ex-officio member of the board, asserted that Cocking wanted to integrate a demonstration school in Athens. The governor announced that he would remove any person in the university system who advocated “communism or racial equality.” After heated debate the regents, most of whom were Talmadge appointees, decided by a vote of eight to four not to reemploy Cocking.

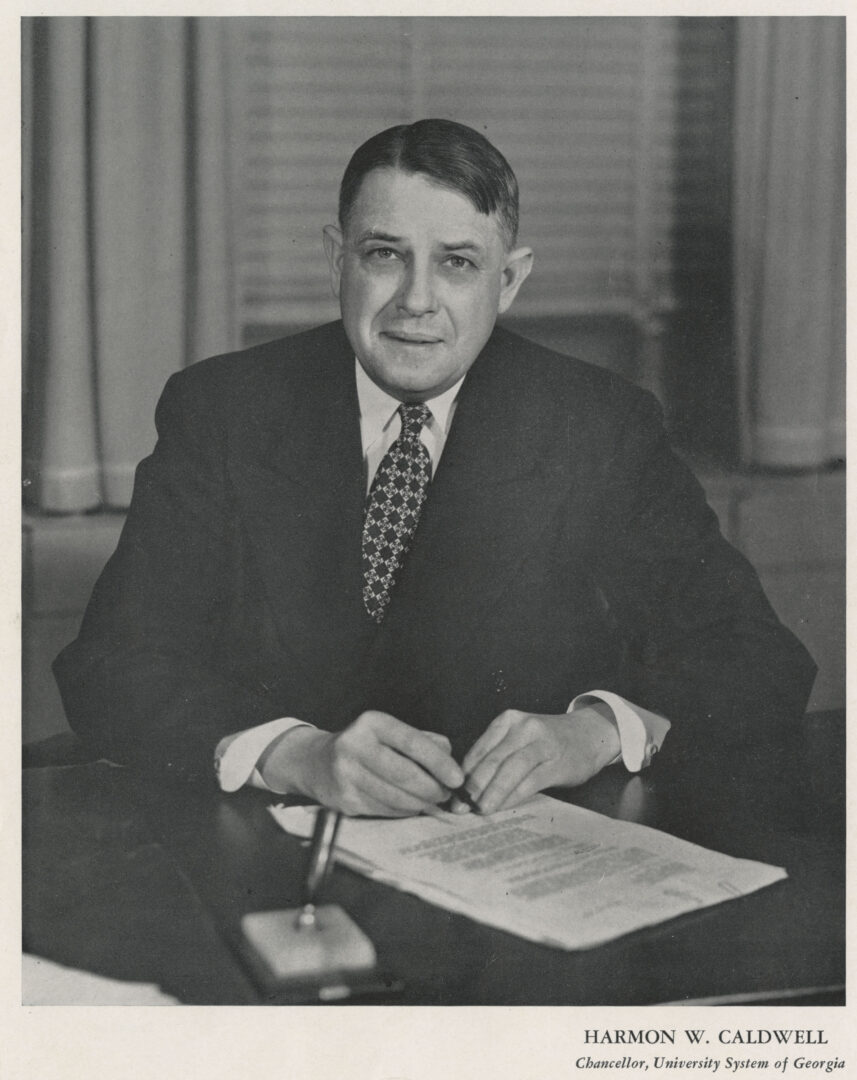

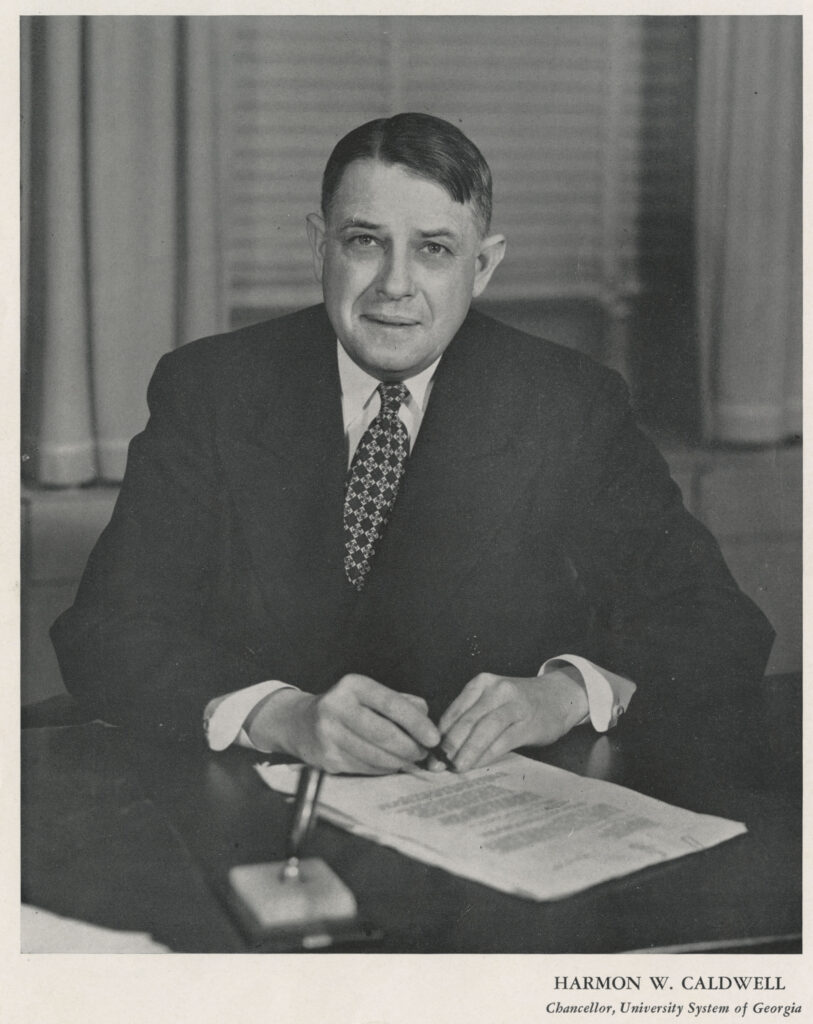

When the regents reconvened that evening after dedicating a building, they learned that Harmon Caldwell, president of the university, would resign unless Cocking received a hearing. After acrimonious debate the regents, unwilling to lose the services of the esteemed Caldwell, reconsidered their earlier action and agreed to permit Cocking to answer the charges brought against him at the next board meeting.

Realizing the potential danger the Cocking case posed to higher education, forty-three senior faculty members at the University of Georgia sent a letter to Talmadge urging him to reconsider his stand against Cocking. These professors, who had daily contact with Cocking, discounted as “misinformation and misrepresentation” the rumor that he was not in sympathy with the southern view on race problems, and they praised him as a leader with “rare executive ability.”

At the June 16 meeting of the regents, the only evidence presented against Cocking was an affidavit by a disgruntled teacher in the College of Education, which charged that Cocking wanted to integrate a demonstration school near Athens. Numerous faculty members and graduate students as well as documentary evidence refuted her accusation. A number of Georgia’s most distinguished educators testified on behalf of Cocking. Harvey Cox, president of Emory University, described Cocking as “one of the best men in the field of education in the South.” With overwhelming evidence in support of Cocking, the regents reappointed him as dean of the College of Education by a vote of eight to seven.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Furious at the outcome, Talmadge then launched newspaper attacks on Cocking’s background, his racial views, and his relationship to the Rosenwald Fund, which the governor referred to as “Jew money for niggers.” He also made sure the next vote would go in his favor by removing three members of the Board of Regents and replacing them with Talmadge stalwarts. In view of the governor’s actions, no one was surprised when at the July 14 meeting the regents decided not to rehire Cocking. The vote was ten to five.

The dismissal of Cocking was merely the beginning of an assault on education that had far-reaching repercussions. Within a year ten outstanding educators (including the vice chancellor of the university system) had been dismissed, the Board of Regents had lost its independence, libraries had been purged, administrators had been intimidated, the morale of teachers had fallen to a new low, and public confidence in the state’s colleges had been badly shaken.

The Southern Association found “gross political interference” in Georgia’s schools and removed accreditation from Georgia’s state-supported colleges for whites. The education purge proved to be Talmadge’s worst political blunder: he lost the 1942 gubernatorial race to young Ellis Arnall.