In early cases, such as Fletcher v. Peck (1810), the U.S. Supreme Court flirted with the notion that American citizens may possess rights enforceable against governments even when those rights are not spelled out in the U.S. Constitution. The Court may have been willing to entertain this idea in part because the original Bill of Rights applied only to the federal government and not to the states.

One key consequence of the Civil War (1861-65), however, was the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, which broadly (but obliquely) stipulates that: “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” After the “privileges and immunities” clause was given a narrow interpretation in an important ruling handed down in 1872, the Court turned its attention to the nature of individual rights made enforceable against states by the Fourteenth Amendment’s separate due process clause. In a key line of cases, the Court concluded that virtually all the Bill of Rights guarantees—such as the rights to a jury trial, to the assistance of counsel, and to confront one’s accusers—had been “incorporated” into the due process clause and thereby made applicable to the states. These incorporation decisions did not concern only the procedural safeguards afforded to criminal defendants; they also barred the states from, for example, interfering with the substantive rights of free speech and the free exercise of religion protected by the First Amendment. The question next arose of whether this so-called substantive due process principle embraced fundamental liberties that lay outside the express protections of the Bill of Rights.

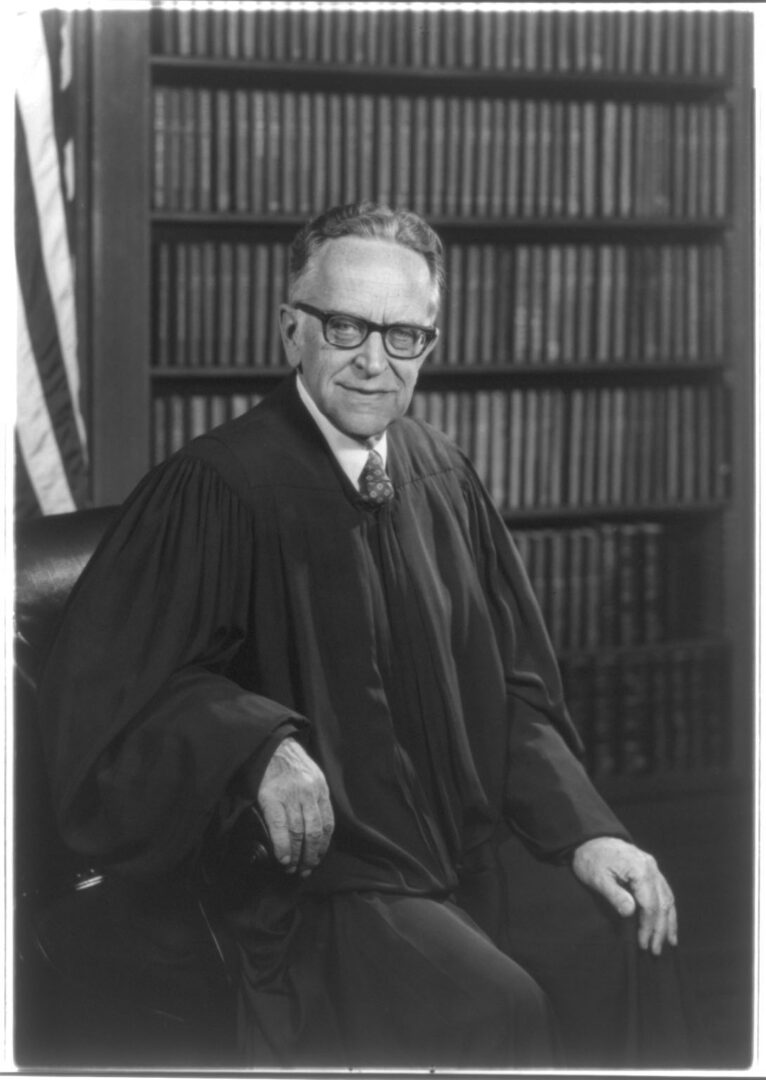

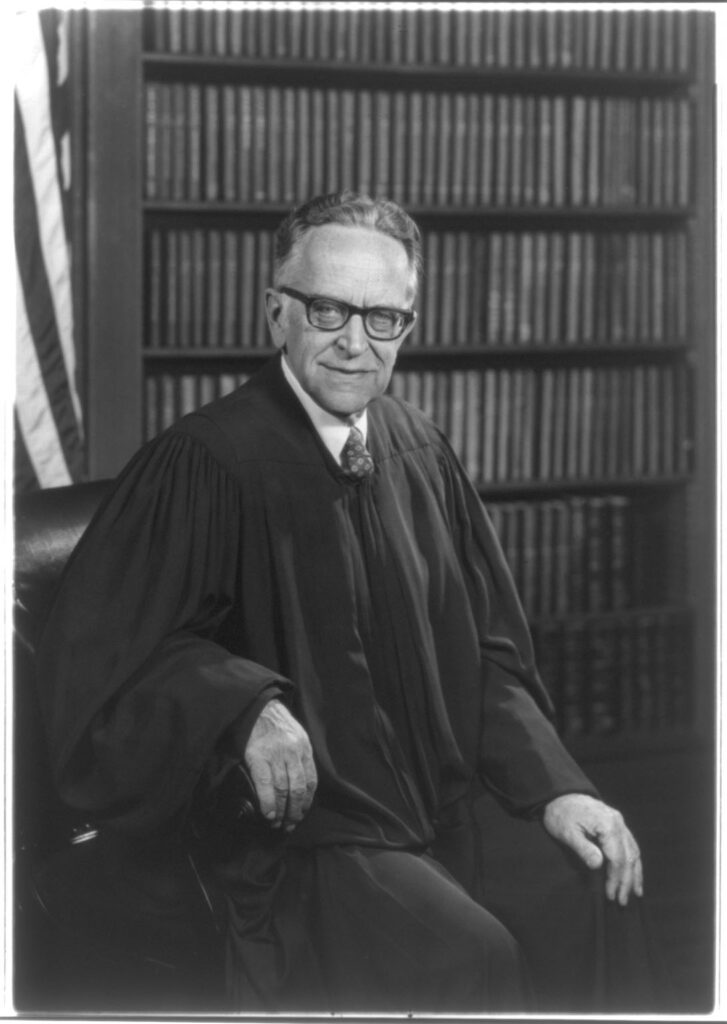

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In a series of decisions dating back to the early twentieth century, the Court held that such protections do exist. In cases decided in the 1920s, for example, the Court suggested that the due process clause puts limits on state authority to interfere with private parental choices about the upbringing of children, even though no text in the Bill of Rights or elsewhere in the Constitution specifically recognizes such an individual right. In later cases the Court continued to speak of substantive liberties, including a “right to privacy,” given protection by the due process Clause. Perhaps the most well known of these cases, Roe v. Wade (1973)—as well as its companion case out of Georgia, Doe v. Bolton (1973)—established the principle that the due process clause affords broad constitutional protection to a woman’s decision to terminate a pregnancy, in consultation with her doctor, prior to the period of fetal viability.

The legal proceedings behind Doe v. Bolton began in 1970, when the Atlanta branch of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Legal Aid Society hired a lawyer named Margie Pitts Hames to challenge the abortion restrictions that Georgia’s lawmakers had enacted in 1968. These restrictions allowed abortion only upon approval by a hospital committee in cases that involved serious threats to the pregnant woman’s health, risks of serious birth defects if the fetus were carried to term, or a pregnancy that had resulted from rape. Hames enlisted Sandra Bensing, a pregnant woman with three children who had separated from her husband, to initiate the lawsuit, as Georgia law prevented Bensing from obtaining an abortion in the state. Bensing sued Arthur Bolton, the attorney general of Georgia, and demanded that the state eliminate the laws that limited women’s ability to obtain abortions. The case was titled Doe v. Bolton, and on January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court announced its verdict.

In Doe Justice Harry Blackmun, writing for seven members of the Court, held that the Constitution rendered invalid not only absolute bans on abortion but also more qualified prohibitions as well. Rejecting in particular the state’s committee-review requirement, the Court spoke broadly of “the woman’s right to receive medical care in accordance with her licensed physician’s best judgment,” free from significant restriction by the government.