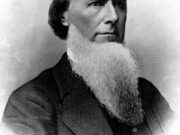

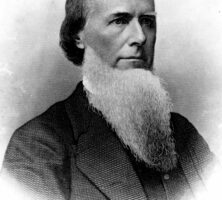

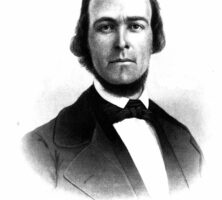

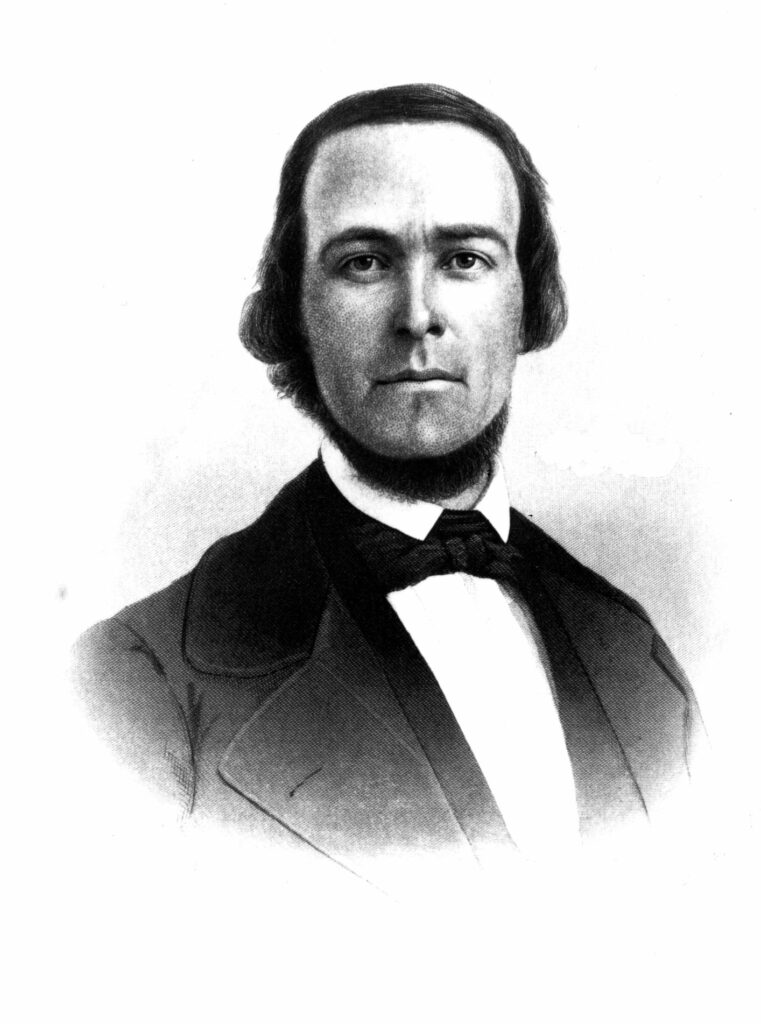

The Civil War (1861-65) governor of Georgia, Joseph E. Brown was one of the most successful politicians in the state’s history and the father of two-term governor Joseph M. Brown.

Born in South Carolina on April 15, 1821, and raised in the mountains of north Georgia, Joseph Emerson Brown capped off a solid middle-class education in private academies with a year at Yale Law School in New Haven, Connecticut (1845-46). Very able and ambitious, Brown quickly prospered as a lawyer and businessman. Soon after his election to the Georgia state senate in 1849, he emerged as a leader of the Democratic Party, and his influence continued after he was elected a state circuit judge in 1855.

Early Governorship

In 1857 Brown edged aside better-known politicians to become the Democratic candidate for Governor. He won decisively, beginning a two-year term in November. From then on he was unbeatable in statewide elections. He never was fully accepted by the established planter elite, but the white masses of Georgia never wavered in their support. Governor Brown clashed with the state banking establishment, compelled the state-owned Western and Atlantic Railroad to operate efficiently, and generally championed the common white people of Georgia. In 1859 he was easily reelected.

As the sectional conflict intensified, Governor Brown became an ardent secessionist. He prodded the legislature to strengthen the unprepared militia and to make other military preparations. After President Abraham Lincoln’s election, Brown called on Georgia to follow South Carolina out of the Union, warning of the dangers of abolition that would lead to miscegenation and racial equality. He ordered the seizure of the undefended federal Fort Pulaski even before a popularly elected convention voted by a narrow margin to secede. The popular secessionist governor may well have tipped the balance in the Deep South state that was least inclined to leave the Union in 1861.

Civil War Years

Governor Brown had been concerned about the growing power of the central government in Washington, D.C. Soon he became increasingly concerned as well about the growing power of the Confederate government, which had moved to Richmond, Virginia, in June after the war started in April 1861. The first disputes over controlling and equipping Georgia forces were ominous, for the Confederacy could hope to win only by a centralized, unified war effort. Soon the disputes escalated, and in April 1862 Brown directly and openly challenged the new Confederate draft. It was the first national draft in American history, a revolutionary but necessary action to mobilize limited Southern white manpower against a vastly more populous enemy. Despite a lack of support by the state supreme court and the legislature, Governor Brown tried to exempt state military forces. As the draft kept expanding and drawing more manpower out of the state, the governor kept resurrecting his forces with Georgians too young or too old for conscription. This became a kind of ritual struggle between the governor and Confederate president Jefferson Davis, accompanied by bitter correspondence, as Brown’s defiance set an example for other states to further cripple the faltering draft. He also provided exemptions for thousands of Georgia men who found jobs in a rapidly expanding state bureaucracy.

Under Brown the state established a mini–welfare system with officials traveling far and wide to supply necessities for soldiers and civilians. He set up an efficient system to distribute scarce salt so that meat could be preserved. As more and more breadwinners marched off to war and fell in battle, needy families multiplied, and the bureaucracy grew to render aid. All this required higher taxes, but Brown made sure the well-off citizens paid their fair share. Neither he nor the Confederate leaders, however, could tame an inflation that was undermining the home front. Within his state, Brown was often efficient and intelligent; indeed, the Confederate government could have learned from the governor’s concern for the men who were doing most of the fighting and dying. These people formed the mass of the white male voters, and they decisively returned Brown to the governor’s mansion in the fall of 1863.

Nevertheless, the hallmark of his wartime administration was his resistance to the authority of the central Confederate government, a policy that was soon copied by some other Confederate governors and that helped to undermine the overall war effort. Governor Brown’s opposition surfaced in many fields. He opposed the army’s impressments of goods and especially enslaved laborers. He frustrated Confederate efforts to seize the Western and Atlantic Railroad and to impose occasional martial law. He bitterly criticized Confederate tax and blockade-running policies. Over time the war-weary legislature backed him more often, and influential politicians like Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens and former secretary of state Robert Toombs became his open allies as morale slumped in Georgia.

Even Union general William T. Sherman’s massive invasion of north Georgia, the beginning of the Atlanta campaign, in the spring of 1864 did not moderate Brown’s disaffection. He still struggled specifically to maintain control of his evolving state militia and generally to resist Confederate authority as Atlanta fell, ensuring Lincoln’s reelection and in turn Union victory. As Sherman’s troops marched virtually unopposed from Atlanta to the sea, breaking the back of Georgia’s war effort, Governor Brown called for peace. Inevitably he denounced the Confederacy’s belated plan to arm enslaved men in exchange for their freedom. His opposition had become almost instinctive; Jefferson Davis could do no right.

Postwar Career

The Confederacy collapsed in April 1865. Governor Brown was arrested and briefly imprisoned in Washington, D.C. Paroled, he backed U.S. president Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policy and received a full pardon in September. Then a Republican, Brown served as chief justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia for two years. As Reconstruction ended, he swung back to the ranks of the Democrats and again prospered in law and business.

Despite his brief dalliance with Republican Party politics, Brown never renounced his support for slavery. What is more, he continued to profit from unfree labor well after the war’s conclusion. Like many prominent Georgians of the postbellum era, Brown amassed tremendous wealth from his reliance on the state’s convict lease system. Hundreds of African American convicts, many of whom were arrested for trivial offenses, were made to labor under deplorable conditions in Brown’s north Georgia mines. A legislative commission that investigated conditions at the mines shortly after Brown’s death confirmed that convicts leased by Brown were threatened by starvation, denied adequate clothing, and were regularly subjected water cure torture. These conditions continued under the ownership of Atlanta developer Joel Hurt, who purchased the mines following Brown’s death.

During his postwar career Brown was a member, along with John B. Gordon and Alfred H. Colquitt, of a group known as the Bourbon Triumvirate, which held much of the political power in the state from 1872 to 1890. From 1880 to 1890 Brown served in the U.S. Senate, until poor health forced his retirement. He died on November 30, 1894.