The Civil War (1861-65) home front in Georgia, far from reflecting unity in a common cause, was rife with conflict and dissent. Though the state was largely spared the impact of invading armies until late in the war, social and economic divisions set Georgians against one another in ever worsening internal conflicts that undermined support for the Confederacy well before the war’s end.

Secession and War

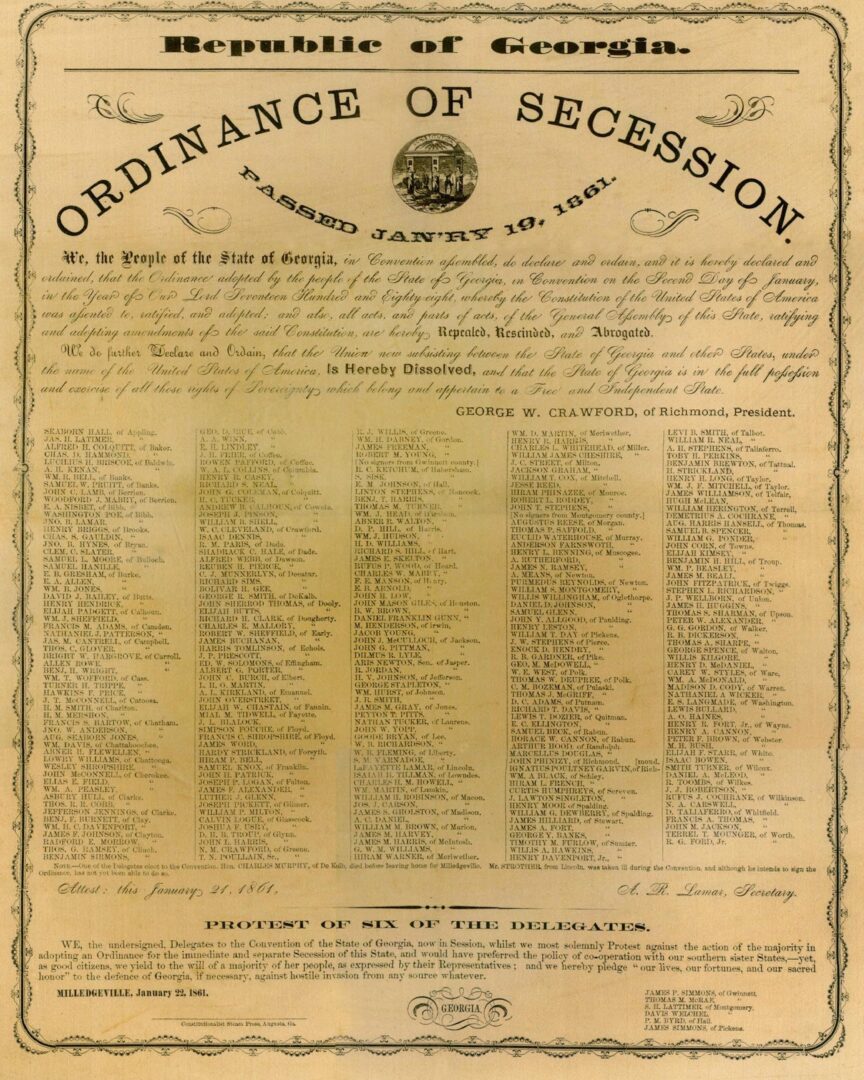

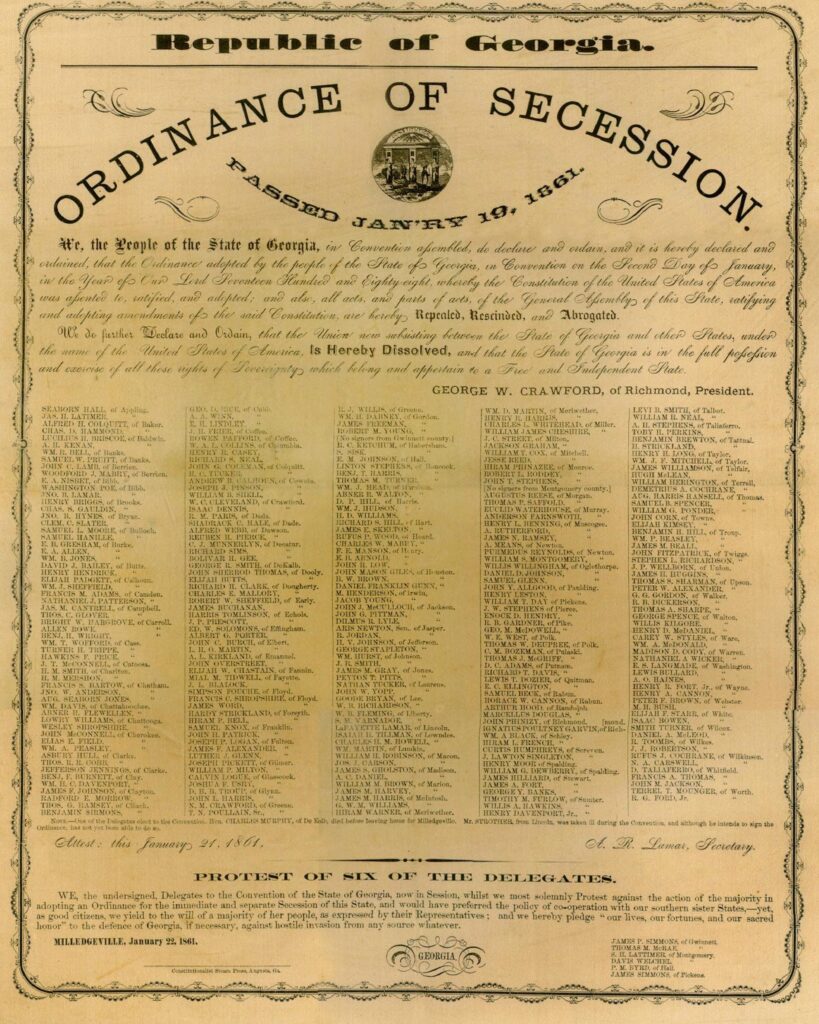

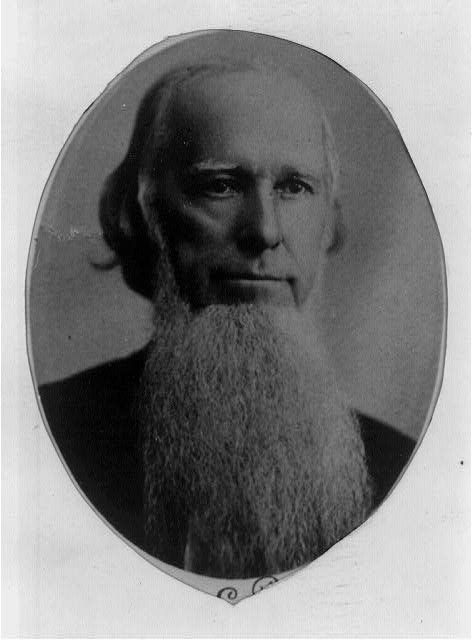

Southerners, including Georgians, were not united in their support for secession. Although, according to historian Michael P. Johnson, more than half the popular vote for delegates to the Georgia Secession Convention of 1861 went to candidates who initially opposed secession, enough delegates shifted their votes to give secessionists a 166 to 130 majority in the first vote at the convention. The remaining antisecession delegates urged that the secession ordinance be put to the people for a vote. Fearing the outcome of such a move, secessionist delegates refused. Georgia, like the other seceding states, left the Union without submitting the issue to a direct popular vote.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

With Georgia out of the Union, opposition to secession continued. Officials in Pickens County flew the U.S. flag over the courthouse for weeks after secession, and some private citizens did the same. One Unionist, James Aiken, informed Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown by letter in February 1861 that he and other residents of Dade and Walker counties adamantly opposed secession. Aiken wrote that secession benefited only “those that owns lands and Negroes!” and threatened that 2,500 volunteers in northwest Georgia would secede from the state if the governor did not put the issue to a popular vote.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Opposition to secession waned after the Confederacy fired on Fort Sumter, in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1861. By the following month approximately 18,000 Georgians had joined the Confederate army, ready to defend the South against Union forces. The most pressing problem for the new recruits was a shortage of food, due in part to the lack of railroads throughout the South but mainly to agricultural practices that favored the cultivation of cotton over food crops.

Cotton and Starvation

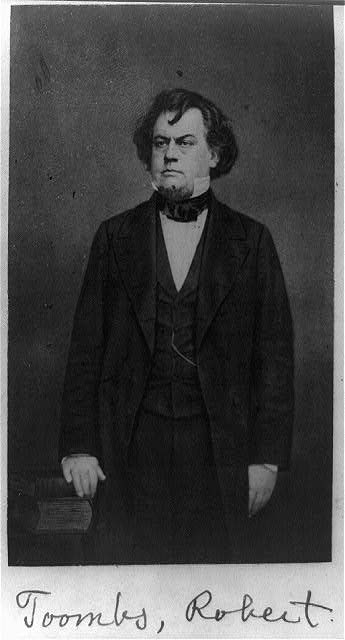

Food shortages led to class tensions and to some of the earliest internal opposition to the war. According to one resident of southwest Georgia, writing to Governor Brown in the spring of 1862, cotton planters amounted to “internal enemies of the country, for they will whip us sooner than all Lincolndom combined could do it.” Despite legal restrictions on the amount of cotton to be grown and exported, cultivation and shipment of the lucrative crop continued. Planters smuggled tons of cotton out of the South, reaping extravagant profits throughout the war. Even Confederate brigadier general Robert Toombs, of Wilkes County, ignored the restrictions, despite protests from his neighbors in Randolph County. The resulting food shortages created extreme hardship throughout Georgia, affecting in particular the women and children of Confederate soldiers. Despite their obligation to provide food for the home front, the state’s planters failed to do so. Moreover, those who did raise food crops often sold their harvest to speculators, who in turn charged more than most yeoman farmers and poor whites could afford.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

On the brink of starvation, women around the state began rioting for food in early 1863. In Columbus a mob of about 65 armed women raided the stores of speculators on Broad Street. Such “bread riots,” as they were known, also occurred that spring in Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, and Milledgeville, and the following year in Savannah nearly 100 women raided stores on Whitaker Street. Women in the rural communities of Blackshear, Cartersville, Colquitt, Forsyth, Hartwell, Marietta, Stockton, Thomasville, and Valdosta also participated in bread riots.

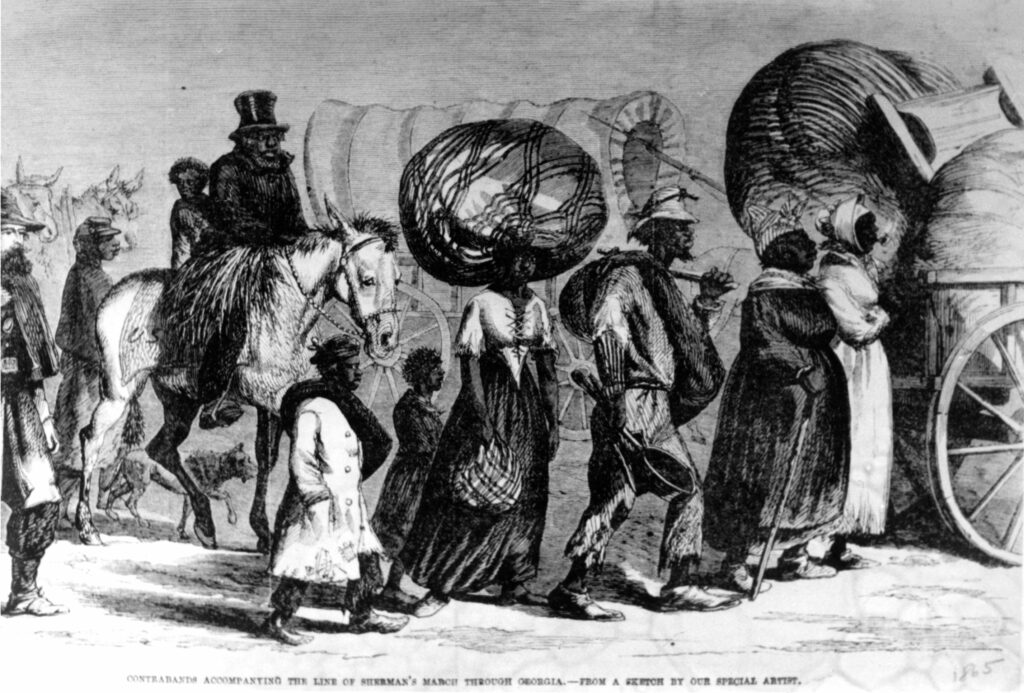

From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

Thousands of petitions describing this desperate situation and begging for relief flooded into Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, from women all across the South. A letter dated September 8, 1863, from soldiers’ wives in Miller County, is typical of these pleas: “Our crops is limited and so short. . . . We can seldom find [bacon] for none has got but those that are exempt from service . . . and they have no humane feeling nor patriotic principles. . . . I tell you that without some great and speedy alterating in the conducting of affairs in this our little nation God will frown on it and that speedily.”

Desertion, Draft, and Resistance

Soldiers’ wives wrote of their distress to their husbands as well, and before the first year of the war had ended thousands of Georgia troops abandoned ranks in answer to their families’ calls. Replacing these deserters was difficult, and attempts by the Confederate Congress to institute a military draft met with much resistance, especially among the working class who did not qualify for exemption by owning twenty or more enslaved persons. Governor Brown, though opposed to the Confederate draft, created his own conscription in order to build up the Georgia militia, but again the wealthy were easily able to avoid service, creating animosity among the poorer classes.

Although many deserters returned home to help their families, others took refuge in the mountains of north Georgia and the wiregrass region of south Georgia. One officer called the state’s southern region “one of the greatest dens for Tories and deserters from our army in the world.” These “tory” (anti-Confederate) or “layout” gangs engaged in raids and battles in order to survive and resist arrest. One such group formed a battalion called the Volunteer Force of the United States Army from Georgia. In early 1863 Governor Brown sent the state militia to put down deserter gangs around Dahlonega with little success, and a year later he sent an expedition against anti-Confederate gangs to southeast Georgia. Such efforts had little effect.

From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

African Americans in Georgia also found means of resistance, particularly in their attempts to secure freedom from enslavement. Rebellion attempts involving both Black and white Georgians were put down in Calhoun County in 1862 and in Brooks County in 1865. Thousands of Blacks joined the forces of Union general William T. Sherman during the March to the Sea in 1864, and many found refuge on the state’s coastal islands.

A Rich Man’s War

On April 5, 1865, only days before the Confederacy’s collapse, an Early County newspaper, the Early County News, published an editorial that reflected a common feeling on the Georgia home front. “This has been 'a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.’ It is true that there are a few wealthy men in the army, but nine tenths of them hold positions, always get out of the way when they think a fight is coming on, and treat the privates like dogs. . . . There seems to be no chance to get this class to carry muskets.” Such attitudes had long since undermined support for the Confederacy and have led many scholars to conclude that internal dissent, as much as the invading armies, was a significant, perhaps decisive, factor in the war’s outcome.