The U.S. Supreme Court’s most famous abortion decision, Roe v. Wade (1973), as well as its companion case out of Georgia, Doe v. Bolton (1973), focused on the proper contours of the substantive protection of liberty enforceable against states afforded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. An earlier decision concerning this same subject, though in a very different context, came in Stanley v. Georgia (1969).

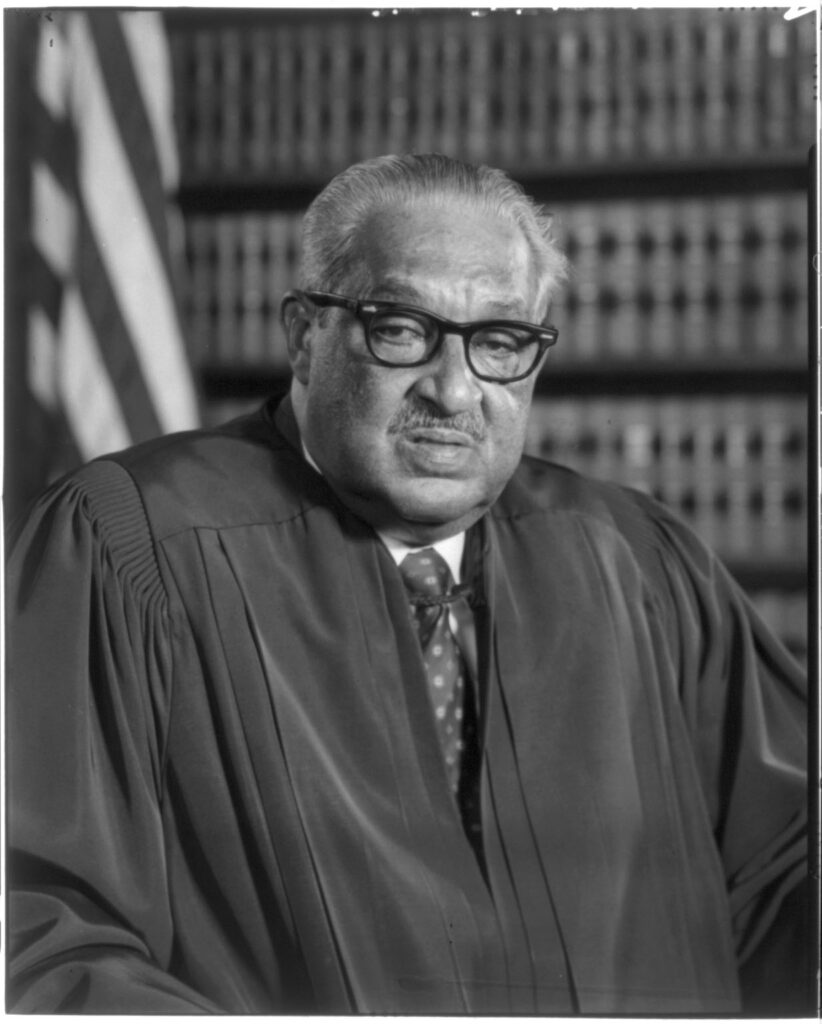

In the Stanley case the Court held that an individual has a constitutional right to possess obscene materials within the home even though obscenity does not ordinarily enjoy protection under the First Amendment’s “free speech” and “free press” clauses. In an opinion by Justice Thurgood Marshall, the Court declared that “fundamental is the right to be free, except in very limited circumstances, from unwanted governmental intrusions into one’s privacy,” particularly the”right to satisfy [one’s] intellectual and emotional needs in the privacy of his own home.”

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Drawing on earlier decisions, the Court emphasized the “right to receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth” and declared that the “makers of our Constitution… conferred, as against the Government, the right to be let alone—the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized man.” Cutting a channel for future legal developments, the Court also suggested that a constitutional claim of the right to privacy “takes on an added dimension” when it involves activity “in the privacy of a person’s own home.”