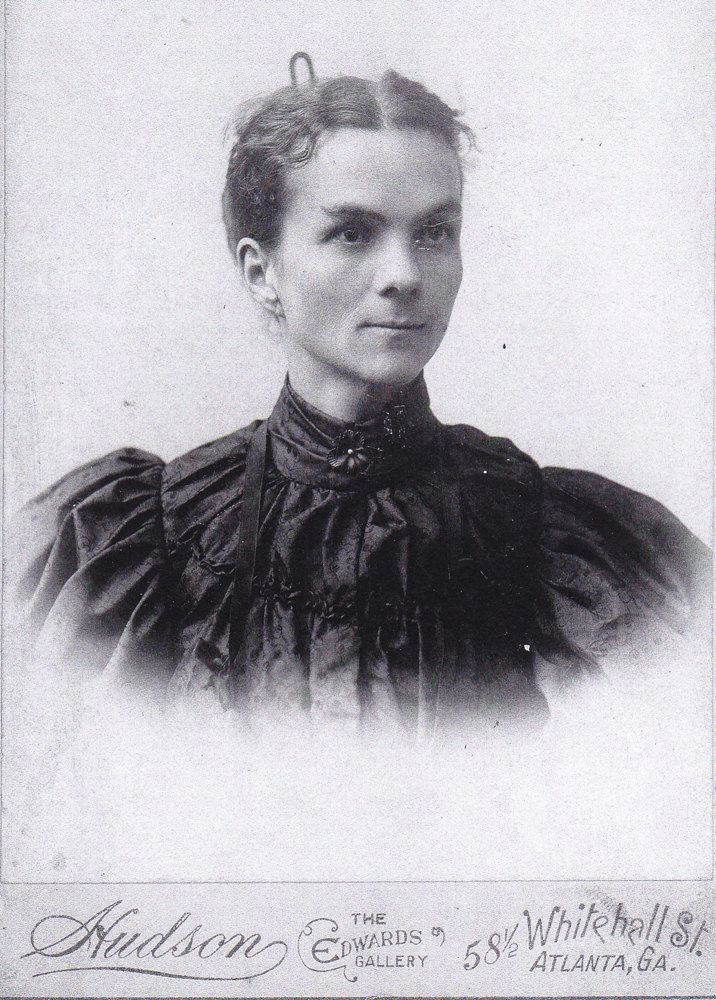

Adella Hunt Logan was an African American teacher, clubwoman, and suffragist known primarily for her activist work in education, public health, and women’s rights.

Adella Hunt was born during the Civil War (1861-65) to a white planter and a free woman of African and Cherokee descent. After attending W. H. Bass Academy in Hancock County, she continued her education at Atlanta University, earning an upper normal division diploma in 1881. That same year, she began her teaching career at American Missionary Association in Albany.

Tuskegee Institute

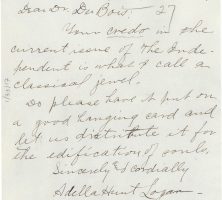

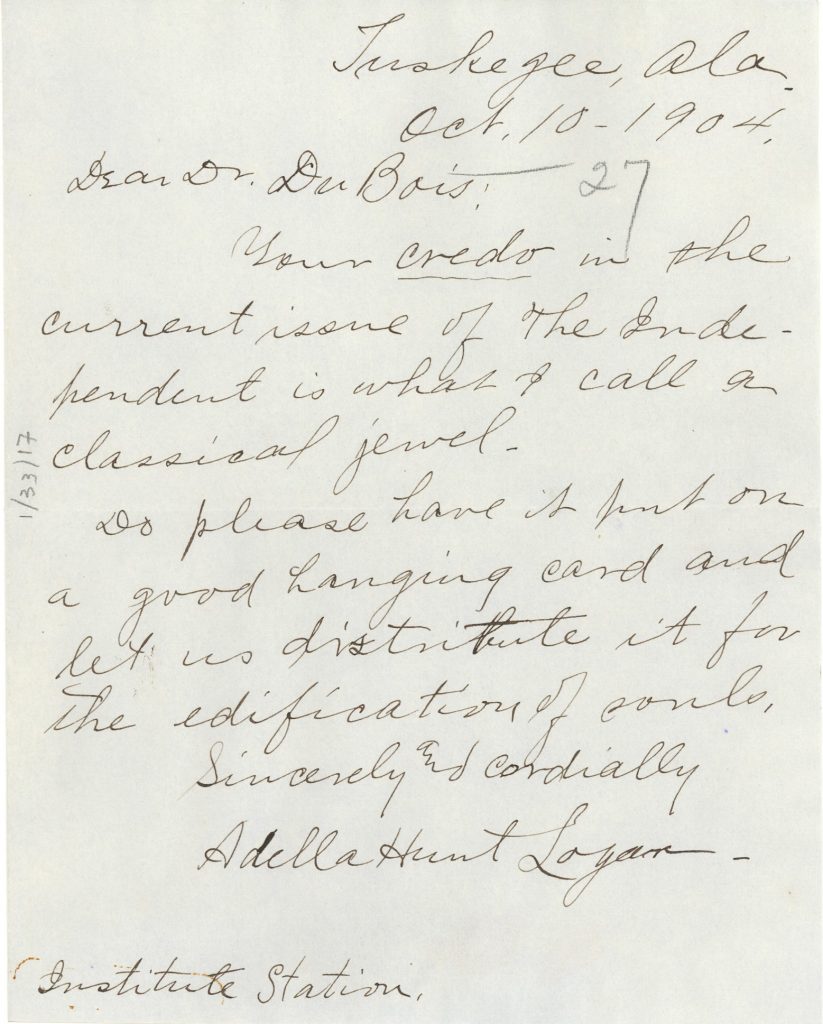

In 1883 Hunt became only the second woman to join the faculty at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where she forged close friendships with the Institute’s founder and principal Booker T. Washington, fellow teacher George Washington Carver, and W. E. B. DuBois, cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Though Du Bois declined a teaching appointment at Tuskegee, Hunt continued a lifelong correspondence with him. After undertaking additional coursework at the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Institute in New York, she completed a master’s thesis under DuBois’s direction and was awarded an honorary master’s degree by the trustees at Atlanta University (the degree was “honorary” because the school was not yet accredited to grant graduate degrees).

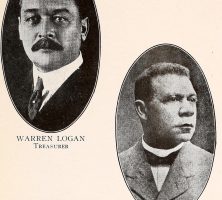

In 1888 she married Warren Logan, the school’s treasurer. The couple had nine children, but only six reached adulthood.

Hunt Logan played an integral role in the development of Tuskegee’s curriculum. As the school’s first librarian, she stocked the library with material on women’s suffrage. She taught English and social studies and served as temporary coprincipal, expanding the program to include skills such as mathematics and literature. In addition to teaching, Hunt Logan joined the Tuskegee Woman’s Club in 1895, where she led discussions and participated in debates regarding racial uplift, education, prison reform, and women’s rights.

Women’s Suffrage and the Club Movement

During the early Progressive Era, women launched campaigns for various social and political reforms, with an emphasis on the right to vote. Black women were excluded from mainstream women’s suffrage organizations like the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which was headed by white suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt. Because she was able to pass as a white woman, Hunt Logan was able to attend meetings held by white suffragists, including the 1895 NAWSA convention in Atlanta.

Hunt Logan and fellow African American suffragists mobilized at local and national levels as part of the Black women’s club movement. In 1896 clubwomen established the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), and for years Hunt Logan headed their suffrage department. During the early 1900s, she contributed poems and articles on Black women’s suffrage to nationally recognized African American periodicals, such as Colored American Magazine and NAACP’s The Crisis. A dedicated member of the Tuskegee Women’s Club, she helped orchestrate a march on Tuskegee’s campus that drew several hundred supporters in 1912.

While living in Alabama, Hunt Logan often returned to Georgia to lobby for social reform alongside other Black women activists, including Victoria Earle Matthews, Janie Porter Barrett, Lucy Craft Laney, and Selena Sloan Butler. In 1897 she delivered one of her best-known speeches at the second annual Atlanta Conference to Study the Negro Problems at Atlanta University. This speech, “Prenatal and Hereditary Influences,” was emblematic of Hunt Logan’s advocacy for the welfare of Black women and families. In her lifetime, she also spoke out against lynching and segregation on railway cars.

Later Years

Hunt Logan struggled with depression, which was exacerbated in 1915 by the death of Booker T. Washington and rumors of her husband’s infidelity. After a brief stay in a Michigan sanitarium, Logan jumped from the fifth floor of a Tuskegee campus building and died on December 12, 1915.

While Hunt Logan did not live to see the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, her lifelong activism and contributions to the fight for women’s suffrage are preserved through her writing and familial legacy. Her granddaughter, historian Adele Logan Alexander, worked diligently to recover Hunt Logan’s life and published a family memoir, Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist’s Story from the Jim Crow South, in 2019.