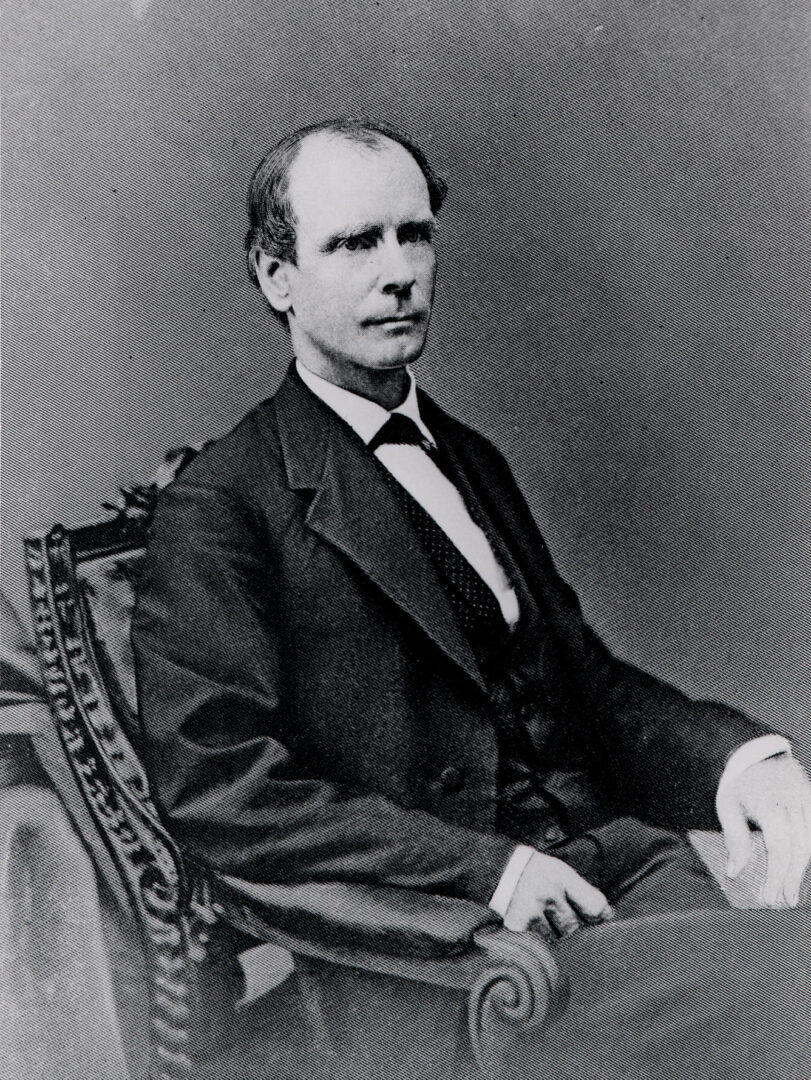

Amos Tappan Akerman was a Georgia lawyer who rose to prominence as U.S. attorney general during Reconstruction. He was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on February 23, 1821. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1842, he went south to teach, first in North Carolina, then in Richmond County, Georgia. In 1846 Akerman accepted a position as tutor in the Savannah home of John Macpherson Berrien, U.S. senator and former attorney general. As he taught the Berrien children, Akerman studied law in the senator’s library, and he was admitted to the Georgia bar in 1850. He practiced first in Clarkesville, then in Elberton. In 1864 he married Martha Rebecca Galloway, with whom he had eight children, one of whom died.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

During the Civil War (1861-65) Akerman supported the Confederacy and enlisted in a home-guard unit. He joined the Republican Party after the war (he had not been politically active before) and served on the state convention that drew up the Constitution of 1868, with its guarantees of equal political rights for African Americans. That autumn, over Akerman’s protests, the white majority in the state legislature expelled twenty-eight duly elected Black members.

President Ulysses Grant appointed Akerman federal district attorney for Georgia in 1869 and in June 1870 named him U.S. attorney general. The appointment was a surprise to everyone, including Akerman. He took office as head of the newly formed Justice Department, which had been created to handle all of the federal government’s litigation (previously, each department hired its own lawyers on a case-by-case basis), and he began the department’s first investigative unit, which later became the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

One of the biggest issues Akerman faced was that of federal land subsidies to railroad companies constructing lines in the West. Akerman’s ruling that the railroads’ commitments had to be fulfilled before the land could be granted earned him the enmity of the railroad “robber barons.”

The problem that most consumed Akerman, however, was the Ku Klux Klan’s efforts to deny African Americans their newly gained rights. Akerman prized the stability of the law above almost everything else, and he resented the fact that some southerners so easily disobeyed the U.S. Constitution, which by then, through the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, recognized that Blacks and whites had the same civil and political rights. As attorney general Akerman strenuously investigated and prosecuted Klan activities, and under his leadership the Klan was effectively ended. According to the historian William McFeely, “Perhaps no attorney general since… has been more vigorous in the prosecution of cases designed to protect the lives and rights of Black Americans.”

Not everyone in the Grant administration shared Akerman’s anti-Klan zeal, however, and some, such as Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, were actually put off by it. That, in addition to the criticism of powerful railroad interests, led Grant to ask for Akerman’s resignation in December 1871. Earlier that year Akerman had moved his family from Elberton, where whites opposed his active support of Black suffrage, to the milder racial climate of Cartersville, where he resumed practicing law.

Akerman died after a sudden attack of rheumatic fever on December 21, 1880, and is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Cartersville. In 2019 the Georgia Historical Society erected a historical marker commemorating Akerman’s legal career at the site of his former home in Cartersville.